A Bill of Rights for the Brazilian Internet (“Marco Civil”) – A Multistakeholder Policymaking Case

This case study by the Institute for Technology and Society at Rio de Janeiro State University explores the events that led to the passing of the “Marco Civil da Internet” legislation, which Brazil enacted in April 2014. The first of its kind anywhere in the world, Marco Civil is a landmark “Bill of Rights” for the Brazilian Internet users. This case study explores the unique features of that drafting process.

Photo: Ninja Midia (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Photo: Ninja Midia (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A Bill of Rights for the Brazilian Internet (“Marco Civil”) – A Multistakeholder Policymaking Case

Authors: Ronaldo Lemos, Fabro Steibel, Carlos Affonso de Souza, Juliana Nolasco

Institute for Technology and Society at Rio de Janeiro State University

Abstract: This case study explores the events that led to the passing of the “Marco Civil da Internet” legislation, which passed in Brazil in April 2014. The first of its kind anywhere in the world, Marco Civil is a landmark “Bill of Rights” for the Brazilian Internet users. The legislative is unique both due to its substance and the process by which it was created. From a substantive standpoint, Marco Civil applies to the Internet key principles such as freedom of expression, net neutrality, and due process. But perhaps more important than the substance is the way in which it was drafted and enacted. This case study explores the unique features of that drafting process. Marco Civil was conceptualized in 2007 and, over the course of many years, was drafted using an open multistakeholder process through which members of the public, government, global and local internet companies, civil society, and others engaged in negotiations over the legislation’s text, largely mediated through online platforms. Although the law was ultimately adopted, the process was not without its challenges. For example, attracting early contributors and participants was difficult, as was debating contentious topics openly among the stakeholders, who frequently disagreed. After many delays, Marco Civil was eventually passed. This case study will explore the factors that enabled a complex piece of legislation to be drafted with input and consultation from a distributed and diverse collection of stakeholders.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. A Brief History of the Project

A. The Political-Economic Settings of the Marco Civil

B. The Mechanics of Consultation

III. Successes of the Multistakeholder Process in Marco Civil

IV. Challenges of Multistakeholderism in Marco Civil

V. Conclusion

I. Introduction

The “Marco Civil da Internet” was the first piece of legislation worldwide to regulate the Internet from the perspective of fundamental human rights. The Marco Civil, passed in April 2014, establishes a comprehensive “bill of rights” for the Internet. Its passage follows both the Web’s 25th anniversary and Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s call for a “Magna Carta” for the Internet. Aside from its unique substance, the Marco Civil is also notable for its multistakeholder policy making process. The Marco Civil, in contrast to other draft bills intended to regulate Brazil’s Internet, was not drafted in a purely top-down or a bottom-up process. Instead, the Marco Civil was drafted through a collaborative and unorganized effort that involved civil society, government (executive and legislative branches), academics, the technical community, and the business sector. As such, Marco Civil was the product of an open and collaborative effort involving an array of stakeholders.

Once it became clear that Brazil needed a bill of rights for the Internet, it also became clear that the Internet itself could and should be used as a tool for drafting the legislation. Following a series of social movements calling for such legislation, the Ministry of Justice, in partnership with academics, began an 18-month consultation process that included contributions from a variety of stakeholders. This consultation was held online and was complemented by a series of in-person events across the country. Once the bill was drafted, it was submitted to Congress, where there was an opportunity for additional online and in-person consultations. Finally, Congress approved the Marco Civil more than seven years after the first consultation.

Article 24 of the Marco Civil enforces multistakeholderism in Internet Governance, by requiring that the federal, state, and city governments must establish multi-participatory mechanisms for governance that are transparent, collaborative, and democratic, and include the government, the private sector, civil society, and the academic community. From start to finish, the approval of Marco Civil embodied this requirement, involving intense debate with several stakeholders. However, to what extent can the Marco Civil be considered a case of successful multistakeholder participation? And to what extent has it inspired advances in other multistakeholder initiatives? This articles analyses both the successes and challenges of the multistakeholder elements of the Marco Civil to address these questions. The work is based on a combination of two methodologies: a set of independent interviews conducted in 2011 with project coordinators (STEIBEL, 2012)[1], and a document and policy notes review undertaken by those running the project.

On one hand we can argue that the Marco Civil was a hybrid and transparent policymaking process that involved contributions from users, civil society organizations, telecom companies, government agencies, and universities, all side-by-side. Each contributor could see the others’ contributions, and everyone placed all their cards on the table to foster open debate. On the other hand, we can argue that Marco Civil was a carefully handcrafted process where, in spite of multistakeholder forums and procedures, the success of the bill is attributable to the active role of key players that pushed the initiative forward.

One way or another the process was successful. The Marco Civil translates the principles of the Brazilian democratic Constitution to the online world. It is a victory for democracy, and for what it stands for. In that sense, the Brazilian Marco Civil goes in the opposite direction of other laws that have been passed recently in countries such as Turkey or Russia, which expand the powers of governments to interfere with the Internet. Brazil’s law is an example of one country placing a strong emphasis on the importance of the Internet as a means of facilitating both economic development, and a rich and open public sphere.

[1] Steibel, Fabro, Beltramelli, F.. Online Public Policy consultations, in Girard, B. ‘Impact 2.0: New mechanisms for linking research and policy’. 1. ed., 2012.

II. A Brief History of the Project

The Marco Civil began in 2007 as part of a strong public reaction against a draconian cybercrime bill. The bill was nicknamed “Azeredo Law”, in reference to a Senator called Eduardo Azeredo, who was the rapporteur and main supporter of the bill. If the bill had passed, it would have established penalties of up to four years in jail for anyone convicted of “jailbreaking” a mobile phone, or for anyone transferring songs from an MP3 player back onto their computer. In many ways it resembled the subsequent SOPA and PIPA legislation in the United States.

Azeredo’s Law had such a broad scope that the bill would have turned millions of Internet users in Brazil into criminals. Moreover, it would have reduced opportunities for innovation by making it illegal to engage in many activities necessary for research and development. Because of this, there was a widespread negative reaction against the Azeredo Law. The first groups to raise their voice were academics, which were then followed by a strong social mobilization, including an online petition that – in a short period of time – received 150,000 signatures. Congress took notice of the reaction and, thanks to this mobilization, initiated a discussion of the topic.

There were many voices against the Azeredo Law. However, there was no clear consensus on what the alternative should be. If a criminal law was not the best way to regulate the Internet in Brazil, then what would be the best way to regulate it? In May 2007, Ronaldo Lemos wrote an article for Folha de Sao Paulo, the major newspaper in Brazil, claiming that rather than a criminal bill, Brazil should have a “civil rights framework” for the Internet: a “Marco Civil”.[2] That was the first time the term appeared in public.

The idea took off, and the Ministry of Justice picked it up. In 2008 the Ministry invited a group of professors, including Ronaldo Lemos and Carlos Affonso Souza (who were at that time leading a research institute at the Fundação Getulio Vargas), to create an open and collaborative process for drafting alternative legislation for regulating the Internet. It was clear to those involved that one could not regulate the Internet without using the Internet itself in the process. They decided to build and launch an online platform for debate and collaboration on the bill at www.culturadigital.org/marcocivil.[3]

The consultation was divided into two phases. The first phase involved consulting with the general public regarding a list of principles proposed for debate (i.e., freedom of expression, privacy, net neutrality, right to Internet access, intermediary liability, openness, and promotion of innovation). The second phase involved examining the proposed draft bill, article-by-article, paragraph-by-paragraph. When the consultation was over, the Government, with the support of four Ministries (Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Communications, and Ministry of Justice) sent the bill to Congress on August 24th, 2011, and it was passed as law on April 23rd, 2014.

[2] Folha de São Paulo, “Internet Brasileira Precisa de Marco Regulatório Civil”. http://tecnologia.uol.com.br/ultnot/2007/05/22/ult4213u98.jhtm, Maio 2007.

[3] The archives of that dialogue are still available at this site.

A. The Political-Economic Settings of the Marco Civil

In 2007, the election of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was an important event for Internet issues in Brazil because he defined improving both the development of technologies and the use of the Internet as priorities for his government. Moreover, the appointment of Gilberto Gil as Ministry of Culture brought in a new perspective on Internet issues and digital culture in Brazil. For example, Gil invested in multimedia studios in the Program “Cultura Viva”, developed new narratives for a Brazilian Digital Culture program inside the government, and identified public policies related to the Internet. Crucially, Gil supported the Digital Culture Forum, the platform that was used for the consultation on the draft Marco Civil legislation.

Another key reason for the passage of Marco Civil was the anger regarding U.S. surveillance activities in Brazil. When Marco Civil was ready for vote, in July 2013, Glenn Greenwald published an article in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo confirming that Brazil was a target of U.S. National Security Agency surveillance. The Brazilian government reacted quickly, and its diplomatic representatives in both the US and Brazil demanded an explanation. As a result, the issue of Internet regulation became a priority for the Brazilian government and the Marco Civil jumped to the top of the political agenda.

The government realized that the Marco Civil could be an eloquent response to the surveillance issue and position Brazil as a global leader in Internet governance and regulatory debates. On September 2013, President Dilma Rousseff made the legislation a matter of constitutional urgency, which prevented Congress from voting on any other issues until the Marco Civil vote was completed. The Marco Civil da Internet locked the agenda of the National Congress and no other vote could take place until the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Congress) voted on the bill. On March 25, 2014, the Chamber of Deputies approved the bill, and it was enacted in April during NETmundial.

B. The Mechanics of Consultation

Government-run consultations are not new in Brazil. In fact, law has regulated such consultations since 2000 (D4176/2000). However, apart from a few experimental initiatives, the Marco Civil was the first consultation to have such a large online focus. The Marco Civil consultation was a joint effort by the Ministry of Justice (the project’s initiator) and the academic center at the Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV). Apart from these organizations, the project also received direct support from the Ministry of Culture, indirect assistance from other governmental bodies (i.e., the Ministry of International Relations), and ad hoc contributions from civil society organizations and Internet activists.

The general objective of the consultation was to draft an Internet law to be submitted to Congress for a vote. The bill was intended to outline a set of legal principles and rights to guide future Internet legislation, and the consultation was fully designed as a collaborative practice. The project ran from October 2009 to May 2010, and it resulted in an online forum where politicians, academics, artists, NGOs, private sector companies, individuals, and other stakeholders could post, blog, debate, and comment on the possible design of the legislation.

The project made use of several web 2.0 tools (mainly the Wordpress platform, Twitter, RSS feeds, and blogs), and it was divided into two rounds of discussion: during the first round people were invited to comment on a white paper that offered a set of general principles that broadly oriented potential legislation. During the second round, people were invited to comment on a draft of the legislation. The first round of the debate tested a set of normative standards, pre-defined by those sponsoring the initiative, that were considered important to include in future legislation. In contrast, the second round focused on receiving feedback on the draft law itself.

During both periods of consultation, participants could comment on pre-defined topics, which related to one of three themes: individual and collective rights (i.e., privacy, freedom of speech, and access rights), intermediary issues (i.e., net neutrality and civil liability), and governmental directives (i.e., openness, infrastructure, and capacity building). Comments during the online consultation were not moderated, and were reviewed after posting by project leaders. Therefore, the online consultation project was a collaborative practice that invited stakeholders to bring ideas to the debate. However, the final decision-making process for incorporating those ideas rested with the initiative sponsors.

Between the first and second rounds of the consultation, project leaders met alone for two days, printed and reviewed all the contributions. These leaders then wrote the draft bill that was used for the second round of the consultation. There were some examples where stakeholder comments led to changes in the proposed text. For example, in the case of intermediary liability policies, the project leaders reversed their initial language based on online contributions. At some point during the consultation, a voting process was established, but it was quickly removed due to a perceived imbalance in the debate. In particular, older contributions tended to receive more votes than new ones, which diminished the incentive to write new comments.

III. Successes of the Multistakeholder Process in Marco Civil

The Marco Civil political negotiation was extremely complex, and took many years. A driving force behind the initiative was the multistakeholder process that permeated the drafting of the bill. It was clear from the start how different stakeholders positioned themselves with respect to the main policy issues. In fact, stakeholders were required to make their positions quite public. The policymakers behind the Marco Civil made efforts maximize the transparency of the stakeholders and positions. For instance, they ensured that the consultation attracted considerable media attention, they rejected contributions received by email and only acknowledged comments published online, and they required stakeholders to identify themselves and be open to public scrutiny and criticism. These efforts helped to reduce information asymmetry and facilitate negotiations. It also helped to facilitate compromises, when necessary. The Ministry of Justice, for example, had to change its position about log records; ISPs and telecommunications companies had to agree to disagree on net neutrality; and civil society was indirectly forced to review their position with regards to the removal of revenge porn.

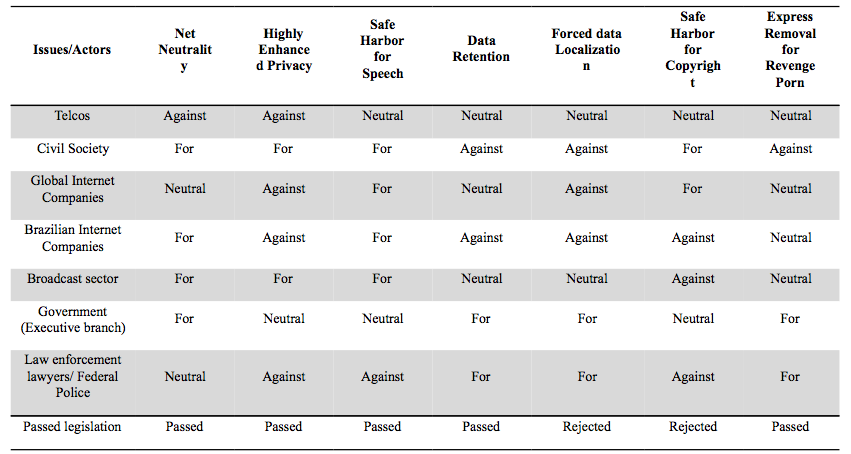

To illustrate the point regarding transparency, Table 1 lists the main controversies of the Marco Civil debate and identifies the positions for each of the main stakeholders[4]. Telecommunications companies, for example, were against or neutral during the whole process around the key issues of the Marco Civil, while civil society was in favor of four of the six analyzed issues, and neutral about the other two. The data comparing stakeholders’ positions suggests, when compared to the text of the final bill, that transparency with respect to stakeholder positions forced trade-offs and brought transparency to negotiations.

Table 1. Summary of stakeholder actors’ positions vs. Marco Civil key issues

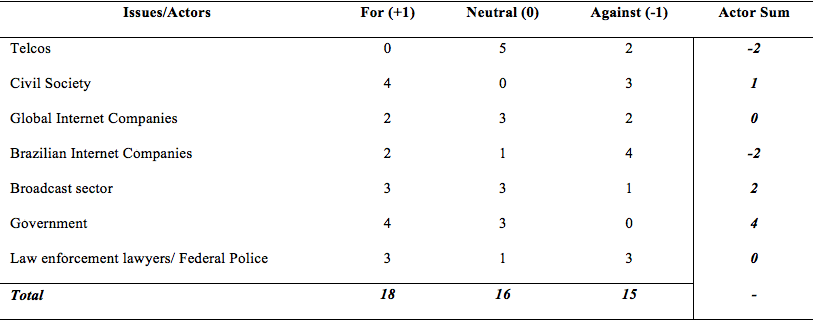

Tables 2 and 3 suggest that the multistakeholder cannot by itself explain the results of the policy process. What we mean by that is that no stakeholder achieved their desired result in every issue, and there was no policy issue where there was a clear alignment among all stakeholders. Using the data from Table 1 regarding the position of each actor for each issue, we can give a value of +1 for in favor, 0 for neutral, and -1 for against. The results of this appear in Table 2. From Table 2 we notice that out of the seven issues identified, the telcos and Brazilian Internet companies were the stakeholders who most opposed the Marco Civil. The telcos were mostly neutral and opposed the net neutrality and privacy provision. And the Brazilian Internet companies both supported and opposed two provisions of the bill. As expected, the government was the most supportive of the bill (+4), never positioning itself against the main issues, but it lost in regards of the issue of Forced data localization.

Table 2. Sum of positions for, neutral or against vs. actors

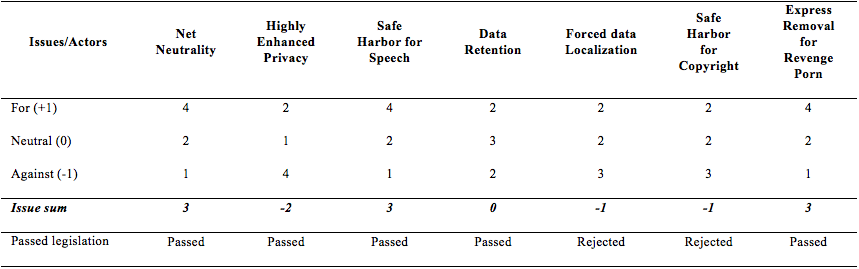

Table 3 illustrates that the stakeholders strongly disagreed about the general issues. This means that no single issue was a major point of consensus amongst all stakeholders, with a distribution of opinions between all possible positions emerging as the most common pattern. Reading the three tables together, we can see, for example, the issue that faced the most opposition (highly enhanced privacy) and the three that found most support (net neutrality, safe harbor for speech and express removal of revenge porn) were all included in the approved bill.

Table 3. Sum of positions for, neutral or against vs. issues

The tables together illustrate the complexity of the Marco Civil negotiation, both in terms of the number of parties involved and in terms of the variety of issues discussed. That said, we argue that although a multistakeholder approach may offer transparency to the policymaking process, it does not necessarily help one predict the outcome of the process. The Marco Civil was an important achievement not only for Brazil but also globally. It is important because of its substance and also its process, representing the intrinsic connection between the open and collaborative process it used, and the substantive results it achieved.

[4] Data portrayed in Tables 1, 2 and 3 are based on previous analysis of the article authors during the years of drafting and approval of Marco Civil.

IV. Challenges of Multistakeholderism in Marco Civil

Often, “multistakeholderism”, is a commonplace mantra, but multistakeholder processes alone were not sufficient in the case of the Marco Civil. In order to solve the contradictions and disputes involved in the Marco Civil it took an intensive negotiation effort. Multistakeholder processes throughout the Marco Civil drafting process were helpful (and important) starting places. However, in order to achieve effective results, it was necessary to engage in debates and negotiations that required actors to put aside radicalism and polarization, and to be ready to compromise during the process. This is one of the main lessons of the Marco Civil[5] process.

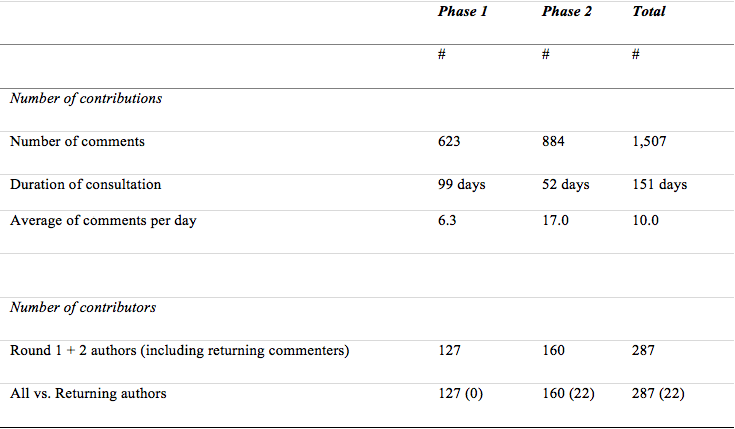

The first challenge of the Marco Civil was attracting a sufficient number of contributors, and prompting them to engage in positive discussion. Based on an extensive analysis of 15 years of online consultations, we can report that the overall volume of participation in the Marco Civil consultations, as measured by number of authors and comments, is significant[6]. More than two thousand comments were posted during the consultations. Excluding the ones that offered little content (e.g., yes/no simple statements, Twitter links, or external references without comments), the online consultations received 1,507 comments and attracted 287 participants (only 22 of them engaging in both phases of consultation).

Table 4. Marco Civil public consultation numbers

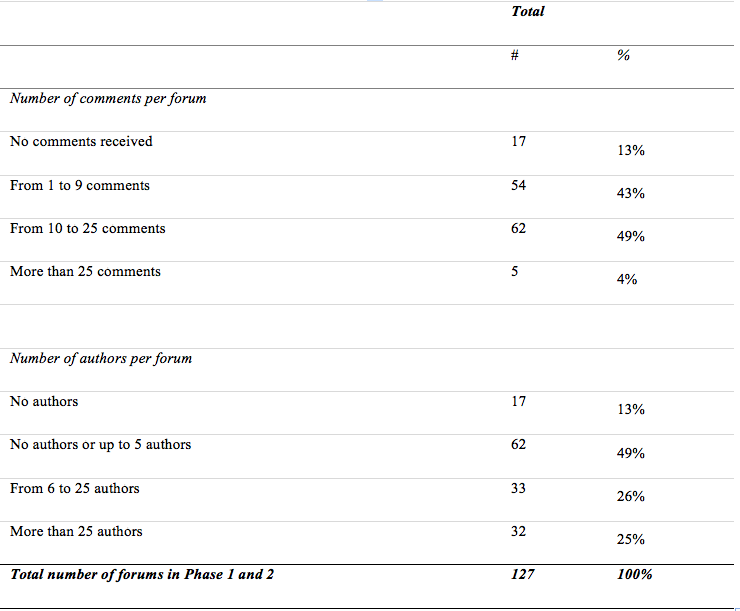

A second challenge of the Marco Civil process was ensuring that all of the topics open for debate received comments and feedback. When we look at the individual forums we find that not all sections of the Marco Civil were discussed in significant detail (even if they were open for debate). A policy forum is defined as an independent comment section within the consultation, so that those who participate in that forum see the other contributions left in the same forum. As Table 5 suggests, out of the 127 policy forums open for discussion during the Marco Civil (rounds 1 and 2 combined), 13% of those forums received no comments, 4% of the forums received more than 25 comments, and in 25% of forums more than 25 contributors participated. However, the overall picture suggests that the Marco Civil process mostly involved forums with around 10 to 25 comments or which involved no more than five authors.

Table 5. Marco Civil policy forums’ profile

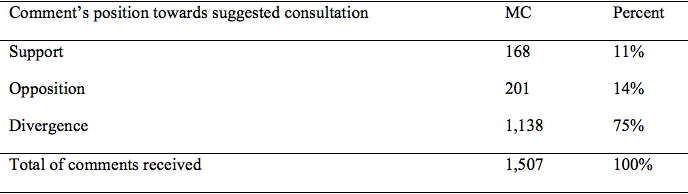

A third challenge faced by the Marco Civil was tracking support and opposition to various issues. We analyze the variation in the number of comments that presented support, or opposition to the specific issue under consideration or diverged from the proposed issue. In our analysis, we find that most comments diverged from the proposed language. Divergence happened primarily in two main ways: (1) the author ignored the suggested policy and suggested an alternative to it; or (2) the author ignores the suggested policy instead supports, opposes, or diverges from another author’s contribution. Taking into consideration that three out of four comments fall into this category (75%), we can argue that the Marco Civil prompted a vigorous debate where the original policy proposal was briefly reviewed and then stakeholders offered a vast range of alternative positions.

Table 6. Contributors’ support for Marco Civil policies

[5] Data portrayed in Tables 4 and 5 are based on previous analysis of the authors, in particular Steibel, F., & Beltramelli, F. (2012). Policy, research and online public consultations in Brazil and Uruguay. In B. Girard & E. A. y Lara (Eds.), Impact 2.0 : new mechanism for linking research and policy. Montevideo: Fundación Comuca. and Steibel, F., & Estevez, E. (2014). Designing web 2.0 tools for online public consultation. (forthcoming).

[6] Coleman, S., & Shane, P. M. (2012). Connecting democracy : online consultation and the flow of political communication. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press.

V. Conclusion

Taken together, the three challenges (a significant but still limited number of contributions; policy forums with a limited number of comments and contributors; and the divergence of contributions) it might seem that the Marco Civil was a unique experience. The Marco Civil process was certainly experimental[7]. However, many elements of the process were less unique: (1) the online consultation was conducted in parallel with in-person consultations across the country; (2) policy debates occurred in traditional media; (3) many parliamentary discussions and online consultations were run by the Congress; and (3) there were several parallel debates in civil society, the business sector, the technical community, and academia.

The challenges faced by the Marco Civil illustrate the importance of a multistakeholder process. A multistakeholder process does not necessarily provide better policies outcomes than a non-multistakeholder process, but in the case of Marco Civil, it enabled a more accessible, participatory, and publically accountable policymaking process. As we describe above, the multistakeholder process in the Marco Civil cannot explain the final results of the bill passed in Congress. Nonetheless, the process gave transparency to the positions of the main stakeholders on the key policies, encouraging stakeholders to negotiate and collaborate.

The online consultations of the Marco Civil process ultimately required a combination of six factors: (a) a government-based institution with a real interest in direct public participation; (b) an active online community with a strong interest in the topic under discussion; (c) an active think tank institution willing to bring its own expertise and influence to the project; (d) a web 2.0 interface capable of engaging policymakers and citizens in a coherent narrative structure for deliberation; (e) policy makers able to identify the key issues for deliberation, determine how technology would be used to mediate deliberation, and to translate contributions into a properly formatted legal policy document; and (f) sufficient resources, backed by in this case by the Ministry of Justice itself, to pay for the project and promote it online and offline.

That being said, the process of the Marco Civil consultations involved a complex culture of perpetual experimentation. To some extent, the online consultations resembled a completely new environment for policy making. For example: policy makers were required to understand the essence of tools such as Twitter and email, and decide if they were suitable for use in the consultation. Based on policy makers’ previous experiences with offline policy forums, they were willing to avoid the one-to-few communication flow in favor of a many-to-many flow online. For example, they decided (after a trial-and-error period) to use Twitter (but not email) to interact with the general public. Ultimately the consultation process supported the eventual enactment of the law. Although it was not possible for participants in the consultations to control the ultimate outcome of the Marco Civil, the fact that the drafted bill reflected the public contributions of several stakeholders made it less likely that the text would be significantly revised after the consultations. Additionally, the community from the consultations contributed to a robust and lasting debate around the bill, which extended until Congress approved the bill and even after passage.

[7] O’Reilly, T. (2010). Government as a Platform. In D. Lathrop & L. Ruma (Eds.), Open government: Collaboration, transparency, and participation in practice.