Creative Commons (CC)

This case study by the Nexa Center for Internet & Society, Politecnico di Torino examines the formal structure of Creative Commons as an organization stewarding the development of the most well-known set of standard public copyright licenses. It highlights how a transnational organization can operate outside of the scope of formal regulatory authority with the purpose of creating an output that has legal weight.

Foto: Kristina Alexanderson (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Foto: Kristina Alexanderson (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Creative Commons (CC)

Author: Federico Morando

Nexa Center for Internet & Society at Politecino di Torino

Abstract: This case study examines the formal structure of Creative Commons (CC) as an organization stewarding the development of the most well-known and widespread set of standard public copyright licenses. In particular, the case study explores the interaction of CC with its own community and with a broader set of international stakeholders during the drafting of the fourth version of the Creative Commons Public Licenses, which took place between mid 2011 (with public discussion starting in November 2011) and November 2013. This case study highlights how a transnational organization can operate outside of the scope of formal regulatory authority, but with the purpose of creating an output (CC licenses) that have legal weight. In such an environment credibility and legitimacy are paramount, necessitating opportunities for public consultation, transparency, and even admitting mistakes.

Table of Contents

I. Preface

II. Introduction

III. Participation

A. The Affiliate Network

B. License Users

C. Funders

IV. Organizational Model and Structure

A. The Governance of Creative Commons Corporation

1. The Professionalization of Creative Commons Corporation

B. The Governance of the Licensing Process

1. Enablers

2. Interaction Between Technical and Non-Technical Stakeholders

3. Interaction Between Geographic Spheres

C. Final Decision-Making Process

1. The Role of Documentation and Institutional Memory

2. Conflict Management and Time

V. The CC 4.0 Versioning Process

A. Background and Brief History of the 4.0 CC PLs

B. The Governance of the 4.0 Versioning Process

1. Final Decisions on the Most Heated 4.0 Drafting Issues

VI. Conclusions and Lessons Learned

I. Preface

This case study examines: a) the formal structure of Creative Commons (CC) as an organization stewarding the development of the most well-known and widespread set of standard public copyright licenses, and b) the interaction of CC with its own community and with a broader set of international stakeholders. The case study focuses on the drafting of the fourth version of the Creative Commons Public Licenses, which took place between mid-2011 (with public discussion starting in November 2011) and November 2013 (when the licenses were finalized and published). This draft case study is based on desk research, written interviews with two senior members of the management of Creative Commons Corporation—Diane Peters, General Counsel and Corporate Secretary, and Timothy Vollmer, Public Policy Manager—, and oral and written interviews with members of the Creative Commons Affiliate Network. Interviews were conducted between July and September 2014. The author of this case study has also been directly involved in the activities of the Creative Commons Affiliate Network since 2006 and, since 2012, has led Creative Commons Italia, the Italian working group affiliated with the CC Network.

II. Introduction

“Creative Commons” is an evocative brand, but this label may point to various and distinct (although tightly interlinked) entities. The Creative Commons Corporation (CCC) is a US-based non-profit organization incorporated under the law of Massachusetts.[1] CC is also a community of people and organizations more or less loosely joined. At the core of this community is the Creative Commons Affiliate Network, which consists of more than 100 affiliate institutions in over 70 jurisdictions around the world. Each affiliate is, in turn, a more or less formal organization providing the focal point for a local community of volunteers. The Affiliate Network, together with other volunteers, participates in the CC mailing lists and online tools (e.g., wikis) where issues are discussed and information exchanged, and in various regional or thematic meetings. Since 2011, CCC has also systematically organized yearly Global Summits where the CC community may meet physically. Similar meetings were also organized prior to 2011, but on a less regular basis, usually in connection with other events and conferences.

The main tool and foremost output of Creative Commons (both the organization and the larger community) is the Creative Commons Public Licenses (CC PLs, or simply CC licenses), which are designed to further CC’s mission.

This is how the official Creative Commons website describes CC: “Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that enables the sharing and use of creativity and knowledge through free legal tools. Our free, easy-to-use copyright licenses provide a simple, standardized way to give the public permission to share and use your creative work—on conditions of your choice. CC licenses let you easily change your copyright terms from the default of “all rights reserved” to “some rights reserved.” Creative Commons licenses are not an alternative to copyright. They work alongside copyright and enable you to modify your copyright terms to best suit your needs.”

The CC Affiliate Network shares the mission of the CCC: “Creative Commons develops, supports, and stewards legal and technical infrastructure that maximizes digital creativity, sharing, and innovation.”

The vision of the CCC is arguably also the cohesive goal of the CC as a community of creators, enthusiasts, and activists: “Our vision is nothing less than realizing the full potential of the Internet—universal access to research and education, full participation in culture—to drive a new era of development, growth, and productivity.”

In practice, CC’s goals are pursued through developing a set of copyright licenses and tools aimed at exercising copyright and related rights in a flexible and overall permissive way—which is consistent, in particular, with the opportunities of circulation and remixes offered by digital technologies. The common trait of the CC legal tools is to provide simple, standardized, and modular ways to allow a certain selection of uses and re-uses (i.e., edits, remixes) of creative works. CC enables all of this without requiring creators to possess a highly sophisticated legal background, without requiring any fees, and while allowing users and re-users (i.e., creators of derivative works) to benefit from the reduced transaction costs and higher interoperability created by a set of standardized legal tools.

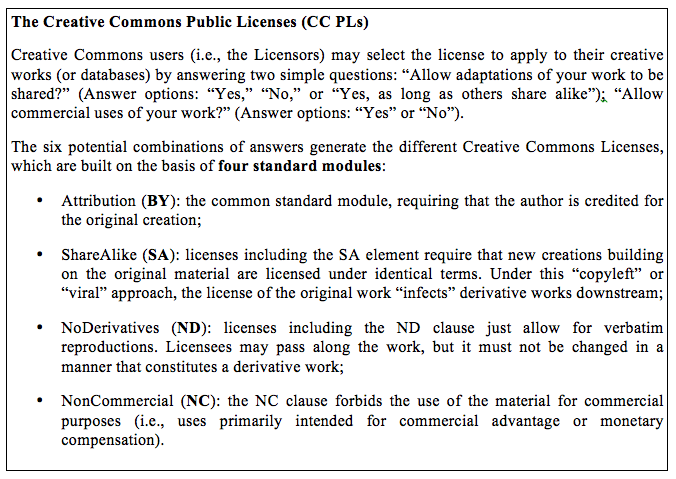

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

As a complement to (or catalyst for) its legal tools, Creative Commons also: (a) raises awareness of copyright law and of the benefits associated with permissive copyright licenses; (b) produces informational and educational materials (standard FAQs, videos, etc.); (c) strives to standardize machine readable metadata concerning licensing (providing its own standard solution, also used by several search engines in their advanced features); and (d) advocates for both free and open knowledge and copyright reform.

This case study focuses on the governance of Creative Commons as an organization, a community, and a standards setting organization, interacting with a broad range of stakeholders to produce, maintain, and develop the aforementioned set of legal tools, which represent a relevant part of the legal infrastructure of the Internet. (As an example, Creative Commons licenses are used by Wikipedia as the legal core of its “social contract,” complementary to its mission as an online encyclopedia that can be edited by almost anyone.)

III. Participation

The Creative Commons ecosystem includes individuals, who choose to use CC licenses, as well as major media organizations, online service providers, academic organizations, and government players. All these stakeholders explicitly influence the governance of CC. Funders are another stakeholder, but the Creative Commons Corporation is committed to remaining independent of funder-driven outcomes, particularly in terms of their impact on the governance of the CC community.

A. The Affiliate Network

The Creative Commons Affiliate Network, which consists of more than 100 affiliate institutions in over 70 jurisdictions around the world, represents the inner circle of the Creative Commons community.[2] The Affiliate Network is a web of diverse organizations, where each affiliate institution is, in turn, the hub of a local community of volunteers.

Typical affiliates are universities (or their libraries) or research centers, mostly with a focus on law or ICT/technology, and other non-profit organizations, mostly associations/foundations working to promote open knowledge, increase digital literacy and education, support free/open source software, or foster digital rights/freedoms. These include some national chapters of Wikimedia and Open Knowledge (formerly the Open Knowledge Foundation). Some affiliate institutions are rather informal or specialized, e.g., hacker spaces or similar meeting spaces in between cultural organizations and co-working facilities.

The CC Affiliate Network is open to new members even in jurisdictions where an affiliate institution already exists. Creative Commons does screen new applicants to the Affiliate Network to ensure adequate resources, and alignment of vision and goals. Upon completion of the screening process, each new affiliate signs a formal affiliate agreement with the Creative Commons Corporation. If an applicant seeks to join the Affiliate Network in a jurisdiction where there is an existing affiliate, then under the terms of the affiliate agreement, Creative Commons must first consult with that existing affiliate(s) before any decision is made.

Affiliate members (i.e., individuals with an affiliation within the Affiliate Network) constitute the backbone of the Creative Commons community, and there is a dedicated and private mailing list for the Affiliate Network, where some discussions take place exclusively. That said, most decision-making processes concerning Creative Commons also involve public mailing lists, where there are virtually no barriers to entry. Therefore, any interested person may have a say within the Creative Commons community. That said, affiliate members typically receive previews of internal drafts, longer comment periods, and other privileges that serve to make their voice more relevant and impactful.

[2] See https://wiki.creativecommons.org/CC_Affiliate_Network for additional information, including the full list of affiliate institutions.

B. License Users

According to the State of the Commons Report,[3] Creative Commons users (i.e., licensors adopting the CC PLs) number in the order of millions. In November 2014, according to statistics derived from Google data, there were over 882 million pieces of CC-licensed content on the Web (they were about 400 million in 2010, 50 million in 2006).

Some of the best-known users of Creative Commons licenses are the following:

- Flickr was one of the first major online communities to incorporate Creative Commons licensing options into its user interface. Currently more than 306 million pictures are available under a CC license.

- Google enabled CC-search capabilities through its main search engine, image search engine, and book search engine, and Google allows users to CC license their own content in Picasa, YouTube, and other applications.

- MIT OpenCourseWare has used CC licenses since 2004 and has over 1900 courses available freely online for anyone, including the right to adapt, translate, and redistribute the content.

- The Public Library of Science’s Open Access journals—such as PLoS Biology, PLoS Medicine, and PLoS ONE—are well-known and respected in scholarly communication.

- Wikipedia, the largest and most cited collaborative free online encyclopedia, uses the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike license as its copyright license.

- The Obama Administration uses CC licenses in various ways, from licensing presidential campaign photos to using the CC Attribution license as the default choice for third-party content posted on Whitehouse.gov (content produced by the administration is automatically in the public domain).

In some cases, Creative Commons interacts directly with major institutions and/or communities that either release a large volume of content under CC licenses, release content with significant cultural or educational relevance, or carry a certain level of prestige. The following are two examples in which Creative Commons interacted with major users in ways that led to significant changes in the CC licenses and/or to significant institutional arrangements.

MIT’s OpenCourseWare project was launched prior to the formal release of the Creative Commons licensing suite in December 2002. Since then, OpenCourseWare has used an early version of the Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike license. Given its extraordinary worldwide reputation, MIT wanted to ensure that translations and adaptations of its learning material were properly described as such, without implying any endorsement of or direct relationship with MIT. To address such concerns, a “No Endorsement” clause was explicitly added to the 3.0 version of CC licenses. In this case, most of the CC community and legal experts agree about the fact that the clause was likely not strictly necessary from the legal point of view (at least in most jurisdictions), but there were similar “No Endorsement” clauses in several free and open source software licenses. Moreover, such a clause would certainly not hurt the overall legal robustness of the license and, as CC put it, it was also useful “to give the licensor comfort and to ensure that the licensee was under no misapprehensions.”[4]

Until 2009, Wikipedia licensed its content with the GNU Free Documentation License (or GNU FDL), a “copyleft” license for software documentation designed by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) for its GNU Project. GNU FDL was one of best standard licensing options available for encyclopedic content when Wikipedia was launched in 2001, but over time it became apparent that GNU FDL was less user-friendly and less widespread (in terms of licensing non-software material, such as ordinary texts and pictures) than the Creative Commons licenses. In December 2007, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales announced that, after a long negotiation, the Free Software Foundation, Creative Commons, and the Wikimedia Foundation had produced a proposal to modify GNU FDL to allow the possibility for the Wikimedia projects (including Wikipedia) to migrate to the CC Attribution Share-Alike license.[5]

When asked about the lessons learned from their experiences with these various stakeholder communities, interviewed CCC staff members stated that CC learned a lot about transparency and consensus-based decision making from the Wikimedia Foundation, Open Knowledge, and the Free Software Foundation. This process is also an example of how these organizations reciprocate with and learn from one another. For example, the Creative Commons Affiliate Agreement (last overhauled in 2011-2012) served as a benchmark for the chapter agreements of both Open Knowledge and Wikimedia.

Governments are another class of major users and relevant stakeholders in the Creative Commons ecosystem. An example of interaction with governments will be discussed below, in describing the background and brief history of the 4.0 CC PLs.

[4] Quoted from https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Version_3#MIT.

[5] For completeness: Creative Commons' initial work had focused on achieving compatibility between the CC licenses, and in particular the 3.0 version, and the GNU FDL. Such negotiation failed, however the FSF agreed to implement some changes in the 1.3 version of the GNU FDL, including a time-limited provision allowing certain materials (produced on "Massive Multi-author Collaboration Sites") to transition to a Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike license without obtaining the permission of every author, which would ordinarily be necessary.

C. Funders

Finally, Creative Commons has mechanisms in place (such as a conflict of interest policy for Board and staff members) to ensure that funders have minimal influence in the governance of CCC.[6] According to our interviews, affiliates seem to share the impression that the influence of funders in the governance of CC is limited and comparatively much smaller than that of actual or potential licensors.

With respect to the perception of the general public, some scant criticism on blogs and mailing lists makes reference to specific corporate interests (e.g., Google), but there is no systematic evidence of criticism of CC on the basis of its relationship with funders (for instance, this aspect is not even touched upon in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_Commons#Criticism).

On the other hand, there is an objective lack of geographic diversity in the funding of CCC primarily driven by its incorporation in the United States, relevant tax laws, and the unique role of philanthropic giving in the U.S. This may contribute to the fact that CCC is still perceived as a US organization, despite its global reach and mission.

[6] Another potentially relevant policy of CCC is the following: A condition of receiving grants is that the output of the activities performed be made available under a CC license (and cannot be owned by the funder)—as CCC staff members put it, this is an “indirect way [that] ensures that foundations abide by our policy of making publicly-funded works freely available.”

IV. Organizational Model and Structure

The Governance of Creative Commons Corporation

Most of the people involved in the Creative Commons community, including most of the active participants in the Affiliate Network, are not aware of the details concerning the governance of Creative Commons Corporation. This is perfectly compatible with an active participation in the community, because the directors and staff of CCC interact with the rest of the community in largely informal (and at the same time very respectful) ways, giving the impression that the most relevant decisions concerning Creative Commons are made by (rough) consensus emerging from interactions within the CC community. That said, decision-making power over everything from the legal tools (which are approved, published, and even technically hosted on the servers of CCC) to the CC registered brand ultimately rests with the Creative Commons Corporation, even if many decisions are made using rough consensus.

As described in the Amended and Restated By-Laws of Creative Commons Corporation (as of 30 April 2014),[7] Creative Commons is a corporation organized under Chapter 180 of the Massachusetts General Laws with no members; CCC’s decisions are made by the Directors of the Corporation. By vote the Directors can set the number of Directors to be five or more; it is currently seventeen. The Directors can also elect their successors. In this sense, it seems accurate to describe CCC as governed by an antipoetic elite, whose legitimacy (which appears to be very strong) arguably comes from the extraordinary standing of the Directors (including academics, practitioners, and activists at the highest levels)[8] in the open knowledge community, and through a track record of successful, careful, and moderate decisions.

The Board of Directors, by majority of the Directors present (including by means of teleconferencing tools) and voting, decides on all material questions affecting the direction of the organization. Some decisions—such as the election of the CEO—may only be taken at the Annual Meeting. Other decisions may be made at other meetings at which there is a quorum of one third of the Directors. Some decisions may also be delegated to subsets of the Board, designated as Committees and including an Executive Committee.[9]

The Board currently does not have designated positions available for affiliates or the community, nor does it have a formal policy on appointing regional, community, or affiliate representatives. Instead, quoting CCC staff, “the Board strives to include members who are representative of the community overall.”[10] This is confirmed by the fact that the current Board includes affiliate network members from Africa, Europe, Latin America, and Asia-Pacific. Thus, while no formal mechanism exists to ensure the participation of specific representatives of the Affiliate Network, or of the CC community, as a practical matter the Board has taken steps to ensure a fair representation by affiliates from various regions. This applies both to the Board itself and its Advisory Council, where all five regions are represented.

Interestingly, in the past, Creative Commons did have a formal process by which two Board members were selected based on recommendations from the Affiliate Network.[12] The Board no longer actively supports that process and policy. CCC staff as described in the following way the reasons for discontinuing this policy: “In the end, CC believed it could accomplish the same balance in its board make-up without resorting to formal seats, believing that if seats were reserved that those board members may be considered “representatives” of the particular region or jurisdiction from which they came rather than a representative for all of CC, which was strongly preferred.”

Even if the Board of Directors provides strategic guidance to CCC, the day-by-day activities are fully managed by a staff of employees. Currently, CCC employs 16 staff members (plus 9 regional coordinators and 2 consultants). Taking into account salaries, other employee-related costs, and all educational and international activities funded through CCC, the costs in 2011 and 2012 were 2.5 million USD.[13]

From the governance point of view, the core CC staff at Creative Commons Headquarters (CC HQ) is comprised of the following people:

- The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is the president and chief executive officer of the Corporation. The CEO has general supervision and control of the business of the Corporation (subject to oversight by the Directors).

- The Treasurer is the chief financial and accounting officer of the Corporation.

- The Secretary is the Clerk of the Corporation, taking minutes and supporting the Board and its committees and councils in their work.

- The General Counsel is worth an explicit mention amongst the other officers, since the General Counsel is responsible for the management of the organization’s general legal affairs. Such affairs are especially relevant for Creative Commons, considering its focus on legal standardization issues.

- The Affiliate Network Coordinator is also worth explicit mention, as the person who is responsible for ensuring that CC staff and those representing the regions (described below) remain in close contact on matters affecting the affiliates and that affiliate views are represented in staff decisions.

Although not employees, Creative Commons has Regional Coordinators (RCs) responsible for overseeing the efforts of CC’s volunteer affiliates around the globe.[14] At present, there is at least one RC for each of the Middle East, Africa, Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America. The RCs report to the Affiliate Network Coordinator, who is part of the leadership team of Creative Commons.

[7] For more information, see the corporate charter (http://ibiblio.org/cccr/docs/articles.pdf) and the by-laws (http://ibiblio.org/cccr/docs/bylaws.pdf).

[8] The current Board consists of 17 members, three of whom are non-voting (individual profiles are available at http://creativecommons.org/board).

[9] The Board has established the following committees, which have authority to act in lieu of the full board on certain matters set forth in their respective charters: the Audit Committee, and the Executive Committee. The Board has also established the following additional committee and councils, which do not have authority to act on its behalf but that instead support the Board on matters set forth in their respective charters: the Finance Committee, the Development Council, and the Advisory Council.

[10] This and the following quotations from CCC staff members come from written interviews we conducted during the month of August 2014 with two senior members of the management of Creative Commons. Therefore, in principle, these quotations just represent their personal point of view, and not the point of view of Creative Commons Corporation (which is conveyed by the CC By-Laws and official statements issued by the Board of Directors).

[11] These four areas, plus the Arab world, comprise the five regions into which affiliates are self-organized and in which CCC has appointed regional coordinators.

[12] See https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Affiliates/Board_recommendation_process, where a structured “Affiliate Recommendation Process for Board Candidates” is described (the process was established and refined between 2009 and 2011).

[13] This figure includes the educational and international activities funded through CCC. See the most recent tax return (http://ibiblio.org/cccr/docs/990.pdf) and most recent audited financial statement ((http://ibiblio.org/cccr/docs/audit.pdf)[http://ibiblio.org/cccr/docs/audit.pdf]).

[14] See https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Regional_Coordinators.

1. The Professionalization of Creative Commons Corporation

In the interviews we conducted within the Affiliate Network, some members of the affiliates also observed that during its more than 10 years of life, the CCC staff has undergone a significant evolution (which is arguably common to many organizations). At the beginning, the CCC staff was described as a group of open knowledge activists and enthusiasts, with good professional skills. Today, it is described as a group of professionals, with a good track record of working with “open” organizations.

When asked if this evolution represented a problem in interacting with CCC, those interviewed mostly agreed that it was not an issue. However, some mentioned moments of friction (sometimes seen as an actual crisis) during the transition, e.g., a tendency to create new and more structured duties for the Affiliates, which mostly remained groups of volunteers. (And, at the same time, the personal ties between the Affiliates and the CC HQ were partly diluted by the arrival of new people.) Such tendencies were, however, moderated by calibrating the new tools—new Memoranda of Understanding, explicit roadmaps, etc—to the needs and possibilities of the various affiliates. At the same time, new personal relationships were established, possibly on a different basis than previously, e.g., more on mutual respect for each other’s professional skills than for the fact of being “fellow activists,”

B. The Governance of the Licensing Process

Drafting and stewarding licensing tools is at the core of Creative Commons mission. Consistent with the organizational model and legal structure of Creative Commons, ultimate decision making related to legal tools rests with the Creative Commons Corporation (i.e., with the Board of Directors). At the same time, the broader CC community is extensively consulted both formally and informally (e.g., through informal e-mail discussions or conference calls with sub-groups of experts on specific topics). This interaction between the CCC and the CC community will be described in more detail below, using the 4.0 versioning process as an example (see page 14).

Moreover, all material decisions are publicly documented and explained, with underlying strategic reasons for the decision disclosed. Explanations of differences between all versions are documented on the CC public wiki, with links to announcements and detailed explanations of changes and strategic decisions.[15] The General Counsel directs this process.

The affiliate members interviewed for this case study confirm both that there is a clear perception of the concentration of formal decision-making power and that the overall process is publicly documented in an accurate way. For instance, a member of the Affiliate Network (and admittedly the most critical person amongst the interviewed people) stated that CC governance uses participative formats and tools, but is, at the same time, “highly centralized and non-egalitarian,” in terms of final decision-making power. The interviewed person then added: “Diane [CCC General Counsel] collected very well all the points of view during the consultation process and Sarah [CCC Senior Counsel] and others published regular reviews and updates of the issues, but at the end, Diane took the decisions, which was transparent.” When asked why, in such a context, he/she was willing to collaborate, despite the absence of any monetary or other directly tangible incentives, he/she answered “Affiliates! For discussion and knowledge exchange.” He/she then added that also the interaction with the CC HQ, although non-egalitarian in terms of decision-making power, was always very interesting and fruitful as an intellectual or professional/scholarly exchange of opinions.

Other individuals interviewed, although less critical (and explicit), agreed that the governance of CC is “inclusive,” but also highly “centralized” in terms of final decision making. The interviewees unanimously stated that the fact that decisions are carefully and publicly documented in writing was a key point supporting participation and open discussion.

1. Technological Enablers

Creative Commons is enabled through a variety of means. Here, the definition of enabler is intentionally broad and encompasses everything that supports the good functioning of the CC network and community.[16]

Some simple, but powerful technological enablers are at the core of the CC network and community. Although not high-tech by modern standards, these technical tools are fundamental for the functioning of the CC network. In particular, CC is enabled through its mailing lists. There are lists for license development, community, and technology development, where CCC staff, affiliates, and other stakeholders vet a variety of legal, technological, and adoption-related issues, policy decisions, and other matters.[17] The translation processes—perceived by CCC staff as “more critical than ever”—are supported by a third-party specialized platform (Transifex[18]). In addition, technology and design projects have been increasingly maintained through software versioning tools like GitHub—an example is the recent “State of the Commons” report.[19]

[16] The fact that also the interviewed people understood the term “enablers” in a broad way is confirmed by the fact that interviewed CCC staff included in the list of enablers the Board of Directors “who bring expertise, passion, and credibility to our mission” and funders, adding that “more recently, we have been receiving more funds specifically for growing our affiliate network and supporting their goals.”

[17] A list of CC mailing lists is available at http://creativecommons.org/contact#discuss. These lists collect hundreds of messages per year, with peaks during specific discussions. For instance, the number of messages somehow related with the 4.0 drafting process is arguably between 500 and 1,000.

[18] https://www.transifex.com/projects/p/CC/.

[19] Project online at https://stateof.creativecommons.org/report/; GitHub project at https://github.com/creativecommons/stateofthe.

2. Interaction Between Technical and Non-Technical Stakeholders

Creative Commons aims at incorporating inputs from both technical (i.e., legally and technologically technical) and non-technical stakeholders in its licensing work.

Within the Creative Commons community, the main debates concern “standardization” of technical legal issues in the licensing domain. However, there are also other relevant technical issues (e.g., technological standardization issues) and less technical issues (e.g., community management and general policy positions).

Technological issues mainly concern the standardization of licensing metadata and understanding relevant technologies—e.g., data mining and big data analytics—as characteristics of the environment in which licenses will be used (mainly, although not exclusively, online). The primary avenue for input on technological matters is the cc-development list.[20] There, metadata is often a topic of discussion, particularly in recent years. (Recently, Lawrence Lessig, in welcoming Ryan Merkley as the new CCC CEO, highlighted that CC technological standardization projects are not keeping up with the legal tools: “We celebrate the tremendous achievement of Version 4.0 of our Creative Commons licenses. But we are still at Version 2.0 of the technology that we use to deliver those licenses.” He added that, “Ryan will fix that,”[21])

To offer a concrete example, during the 4.0 drafting process, CC solicited input from various stakeholders on digital rights management (called Effective Technological Measures, ETMs, in the 4.0 licenses) and which restrictions imposed by platforms fell within the definition of ETMs.[22] CC consulted with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), among others, on defining the language to ensure it properly captured the types of restrictions that amounted to legal restrictions, which have always been prohibited by CC licenses. CC also consulted with non-technical stakeholders on the question of what is appropriate attribution for various disciplines, including for scientific data (which the 4.0 licenses now more clearly address) and in the educational and scholarly context (e.g., with respect to open educational resources).

In conclusion, not only does CC solicit contributions from both technical and non-technical stakeholders on their domains of expertise, but it even seeks input on technical issues from non-technical stakeholders, where their contributions can be helpful.

[20] http://lists.ibiblio.org/mailman/listinfo/cc-devel.

[21] http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/42705.

[22] https://wiki.creativecommons.org/4.0/DRM.

3. Interaction Between Geographic Spheres

Some issues are passed between the different geographic spheres of the CC network—e.g., an issue is identified by an affiliate, brought to the attention of CC HQ, comes back to a group of affiliates, and is then discussed in the general mailing lists.

CC does not have a specific policy to manage these processes, other than seeking input on particular issues from those most affected by them and from those with the greatest expertise.

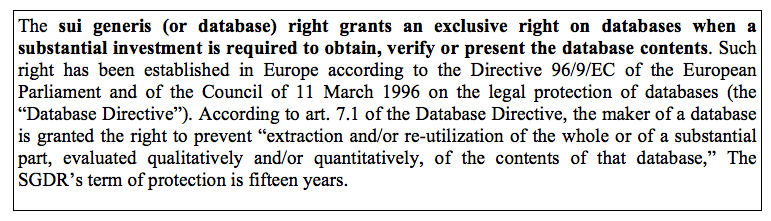

Many legal copyright issues are global in nature, particularly considering that the online environment is the main (although not exclusive) target of CC licenses. Moreover, Creative Commons is striving to increase the standardization of its legal tools, making them directly applicable worldwide, without the need for local adaptations (such adaptations—the porting process, using CC jargon—were necessary for licenses using versions 3.0 or older). For the time being, however, localized conversations are still necessary for many topics. The best example of this will be discussed below, detailing the problems concerning the licensing of sui generis database rights and how those were discussed during the 4.0 licensing process. The licensing experts on the topic were largely from the European Union, where those rights predominantly exist. During the versioning process, CC sent several questionnaires to experts in the EU to discern the nature of the sui generis right, which exclusive rights it covers (and what it does not cover), and its exceptions and limitations. CCC staff members then brought the output of this preliminary (but very detailed) conversation to the larger affiliate community.

i. Scalability

Within the CC network, issues are transitioned both down-sphere (from larger to smaller geographic spheres) and up-sphere (from smaller to larger geographic spheres). Hybrid examples are actually commonplace: specific issues may be identified at the local level, transition up-sphere, and again down-sphere, e.g., if there are concerns that a specific policy challenge may spread to other jurisdictions.

Awareness of issues often starts at the local level with an affiliate or community member surfacing a matter of particular importance to them based on a development in their locality or region. These issues are sometimes raised to the full network and to CC HQ, and sometimes just locally through the regional email lists. The Regional Coordinators and other CCC staff watch for those issues and bring them to the attention of other regions, the entire Affiliate Network, or other HQ staff as necessary.

One example of this process is the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (a proposed trade agreement with potential impacts on copyright protection in multiple countries), which several affiliates flagged as a concern. This concern was elevated to other affiliates in jurisdictions involved in the negotiations, and ultimately CC HQ took policy stances on both the process and substance of those negotiations.

At other times, issues are identified and raised by CCC staff or the Regional Coordinators, and then brought to the attention of the affiliates and broader community. License compatibility is an example of such a situation. Following the publication of the version 4.0 licenses, CCC established ShareAlike compatibility processes and criteria in an effort to address interoperability problems among silos of incompatibly licensed content. The first candidate, Free Art License (FAL) version 1.3, surfaced several matters of policy that would affect the entire Creative Commons community. Those issues have been discussed and pushed down-sphere for consideration by Affiliates. A second example is work on the World Intellectual Property Organization’s proposed Treaty on the Protection of Broadcasting Organizations, which would give broadcasters extensive controls over content they broadcast, even in cases where copyright belongs to others.[23] This treaty would have a global impact and could adversely affect the ecosystem in which CC licenses operate. In this instance, CC staff surfaced and vetted the issue with the affiliates before advancing to a final decision to sign onto statements opposing the progression of the treaty within WIPO.

[23] Electronic Frontier Foundations, “Broadcasting Treaty,” https://www.eff.org/issues/wipo-broadcasting-treaty.

ii. Policy Matters and Geographic Spheres

On matters of policy, CC tends to work regionally rather than globally when a policy is specific to a region. As CCC staff members put it:

“We do, however, strive to inform and solicit any relevant input from the remainder of the network because local or regional policies can have ripple effects in other regions and worldwide. There have been increasing calls for CC to take policy stances on certain topics, for example, but generally CC has been apprehensive to jump in headfirst on this. Our engagement on these matters are informed through interaction by local affiliates on the ground—whether and how CC should respond, is there a more effective organization for doing so [...], and similar. One recent example is the [“Public Consultation on the review of the EU copyright rules”]. The issue was raised by several CC affiliates in Europe, and Creative Commons took notice. The coordination and organization for the input came from the European Regional Coordinators, who are paid CC staff and who in turn solicited responses and input from the affiliates.”

In fact, because of a growing number of calls for CC to take policy stances on various topics (generally related to copyright reform), during the spring of 2013 CCC established (in consultation with the affiliates) some explicit Policy Advocacy Guidelines.[24] Such guidelines promote policy interventions at a local or regional level, and attempt to clearly differentiate between statements from the CCC as opposed to affiliate teams. The hope was that this would empower affiliate teams to speak on their own. Such an approach aims at making it possible for some affiliates to be very active in the policy space (for example, in the Netherlands, Poland, and Colombia, extremely active and well-connected individuals already interact on these issues as a part of their other work or projects). At the same time, CCC can directly take policy stances only in a few defined cases, with the active involvement and final explicit approval of the CCC Board.

In addition to its affiliates, Creative Commons works with other organizations on both formal and informal terms. CC has been a member of the Communia Network (now Communia International Association) on the Public Domain since its beginnings, LAPSI (The European Thematic Network on Legal Aspects of Public Sector Information, and its continuation, LAPSI 2.0), and WIPO (as an observer on the Committee on Development and Intellectual Property). Many CC affiliates are members of these same organizations. To the extent these organizations have a focus or expertise and formulate policy and other interventions, CC works through them rather than on its own.

[24] See https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Policy_Advocacy_Guidelines.

C. Decision-Making Process

As described above, ultimate decision-making power always rests with Creative Commons Corporation. The strategic discussions related to legal tools and policies for Creative Commons are driven by the General Counsel, with the approval of the CEO, and the input of staff and the Affiliates. According to the Affiliate Agreements, CCC is required to provide a comment period for any change in policies that affect the Affiliates’ relationship with Creative Commons. Those policies include the Privacy Policy, Terms of Use, Trademark Policy, Merchandising Policy, the Legal Code and Translation Policy, and similar policies. Those policies are reviewed annually and updated as appropriate. Similarly, the Affiliate Agreements—which formalize CC’s relationship with affiliate institutions and individuals in more than 70 jurisdictions—are regularly updated and vetted with the Affiliates prior to finalization.[25]

With respect to the policy activity of CC, CCC applies the aforementioned Policy Advocacy Guidelines. These detail how Creative Commons makes decisions related to advocacy activities, the means by which affiliates may engage in advocacy activities, and various consultation processes related to both. For instance: “The CC Affiliates are notified [...] about the policy action 24 hours in advance (if feasible) of public communication of that decision. Local affiliates should be consulted when potential policy and advocacy actions originate in their respective affiliate jurisdiction. Local affiliates should assist (and potentially lead) on issues where they have demonstrated expertise.”

While these formal policies exist, and will ultimately rule in case of controversies, a common perception of the CCC staff and of the members of affiliate institutions is that, within the CC network, most decisions emerge from open discussions within the Affiliate Network or with relevant stakeholders at large. Most of these discussions take place on the CC mailing lists (possibly with parallel regular email discussions within sub-groups, which are then “merged” into the main mailing-list discussion). As CCC staff members put it: “Creative Commons strives for general consensus, though that cannot always be achieved,” and “rough consensus” is the preferred plan, whenever possible. In practice, the usual approach is to engage in informal consensus building (including through bilateral discussions between CC HQ and selected affiliates), with final public discussions on mailing lists, where everybody may assess the level of consensus reached. Some variations are also possible, e.g., when a final version is nearly ready, participants are sometimes asked to voice only strong dissent and/or raise only new severe problems, rather than to postpone reaching consensus.

CC is currently undertaking a “more concerted effort to act as a true global network, and not make decisions unilaterally,” One example is the aforementioned policy/advocacy guidelines. When rough consensus cannot be achieved, CCC acts as steward of the CC tools and overall mission and makes decisions based on that mission and the community’s shared vision. In these cases, CC HQ relies on a subset of “go-to” expert affiliates based on trust built over the years, as well as those with specific subject area expertise.

[25] See Agreements and Policies on the CC wiki: https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Affiliates

1. The Role of Documentation and Institutional Memory

An element that emerged in both the interviews with CCC staff and affiliate members is the importance of written documentation and institutional memory. In particular, extensive written documentation of the costs and benefits of the options considered and the reasons for the final decision seems to have minimized any negative responses when decisions are made in a more top-down manner.

The role of institutional memory is described in the following way by the interviewed CCC staff members:

“There is a lot of good to having a network with a long institutional memory—and CC has that, for the most part, since we still have several of our original affiliates involved. The same can be said about the makeup of our Board of Directors where some of the most important policy and other decisions are vetted or reviewed—their ongoing presence provides institutional memory and long-term consistency of vision for the organization and the global copyright ecosystem and its challenges. CC staff, on the other hand, does continue to evolve and with that attrition comes some loss of long-term memory. CC does ensure long-term memory and consistency of position through mechanisms other than its affiliates, board and staff, however. We have a long-standing policy of documenting all important policy decisions and product decisions (licenses, public domain tools, deprecation of legal tools, etc.) on our weblog, and through explanatory emails sent to publicly archived and accessible email lists and for affiliates through our affiliate email list.”

Institutional memory also helps in facilitating reconsideration of past decisions. Using the words of CCC staff members: “Some decisions can be analyzed and decided based on prior experience with similar or same challenges. One good example of this was the change in CC’s position on sui generis database rights. While we had for many years taken the firm stance that our licenses should not be used to license those rights, our experience and engagement with our affiliates in Europe taught to reconsider after many years of experience with that position.”

2. Conflict Management and Time

There aren’t many examples of situations in which the CC network faced a crisis with no viable apparent solutions. The most relevant instance is arguably that of CC’s position on sui generis database rights (i.e, a special intellectual property right on databases specific to the European Union). This issue is an example of a major policy change and it will be detailed below, in describing the drafting process that led to version 4.0 of the CC PLs.

Here, it is also worth mentioning that, sometimes, deferring a decision may be an option, as long as the various merits of other options are documented and the existing discussion is not lost. As the interviewed CCC staff members put it,

“We should note that there are at rare times challenging issues that may sit for awhile or require a more in depth consultation before movement can be made. One excellent example of this was the creation of CC0. When first introduced to the affiliate network at CC’s 5th birthday party in December 2007, it faced extremely strong opposition. Following the iSummit in Sapporo, CC agreed to table its development and publication while investigating more thoroughly its demand and its effectiveness in various jurisdictions. CC surveyed its legal affiliates, engaged additional legal experts, and painstaking rewrote the legal tool to address many concerns, all over the course of the next 1 ½ years. Only upon that further vetting and effort was the community able to generally agree (rough consensus) to lend its support to the new legal tool. To this day, there are a few affiliates who are opposed to its use in some jurisdictions; however, there is general respect for such legal tool and its viability and utility in most all other jurisdictions.”

V. The CC 4.0 Versioning Process

Since the launch of the first CC PLs at the end of 2002, CC has labeled its licenses with version numbers, as is customary for software project releases. Version 3.0 came out in early 2007, while version 4.0 was released in November 2013.

The 4.0 drafting process (“versioning,” using the CC jargon) is described here, as it provides concrete examples of the operation of CC’s governance structure.

A. Background and Brief History of the 4.0 CC PLs

The discussion of Version 4.0 of CC’s core license suite began at CC’s Global Summit 2011 in September 2011 The discussion was recapitulated and expanded to the CC Affiliate Network mailing list in the following months. The public discussion with the broader CC community and with third parties began in December 2011 with a blog post laying out some of the key reasons for developing a new version of the CC PLs.[26] Various issues were discussed in the blog post, but a key point was the following: “version 3.0 is working (and will continue to work) really well for many adopters, but [...] [t]he treatment of sui generis database rights in the 3.0 licenses continues to be a show-stopper for many, including governments in Europe. This fosters an environment in which custom licenses proliferate, inevitably resulting in silos of incompatibly-licensed content that cannot be maximally shared and remixed.”

The use of licenses to enable releasing databases as open data demonstrates that unmet demand quickly generates new licenses. In particular, until recently Creative Commons—because of the position of the Science Commons group—did not want to explicitly adapt its suite of licenses to databases, with the exception of the public domain waiver/dedication CC0. Science Commons argued—not without reason—that data should be and remain in the public domain, taking a de facto policy stance against the European sui generis database right.[27] CC PLs pre-dating the 3.0 version did not mention the sui generis database right;[28] therefore, it was unclear if the CC licenses (apart from CC0) were an appropriate legal tool for the licensing of databases potentially protected by the sui generis right.

When the localized (ported) European 3.0 licenses were prepared, Creative Commons required a clear stance against licensing the sui generis right.[29] Ports of the 3.0 licenses for European jurisdictions explicitly addressed these rights as within the scope of the license, but then affirmatively waived all conditions of the licenses for uses implicating the sui generis right. Said another way, the licenses covered copyright and sui generis database rights, but the conditions only applied to uses implicating copyright that could exist for databases based on selection and arrangement, but not other uses. In practice, the European ported licenses attempted to neutralize the sui generis database right and treat them the same as the rest of the world (where the sui generis right does not exist). Therefore, until the 4.0 licenses were released in 2013, the demand for a full-fledged open license for databases in Europe was still unmet.

It appears that because of CC’s hesitancy to adapt its licenses to databases, in 2010, the UK government decided not to adopt CC licenses for the release of its public sector information. UK officials clearly stated in informal discussions that the government was ready to adopt very liberal licensing approaches, but that waiving rights was not an option (i.e., such an approach was perceived as unnecessarily radical in comparison to liberally licensing the same rights).[30]

Moreover, some open data projects, such as Open Street Map (OSM), started to question whether licensing their data with CC licenses was the best approach. In this case, OSM wanted to adopt a copyleft approach, using existing rights to enforce a viral chain of sharing, and waiving rights to court did not seem to fulfill that objective.

OSM decided to use the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike license for its project. However, because it waived and did not license the sui generis right, some in that community believed OSM’s steps were inadequate. In response to the partially unmet demand for standard licenses for the legal management of databases in the European legal environment, the Open Data Commons project was launched. In 2006, the software company Talis published the first public license specifically targeting open data, the Talis Community License, and then funded the drafting of the Public Domain Dedication and License (PDDL). This activity triggered the creation of the Open Data Commons project, which is currently part of the project portfolio of Open Knowledge. In the same time period, the UK Government released its Open Government License, which was followed quickly by the French License Ouverte and the Italian Open Data License.[31]

It is in this complex scenario that Creative Commons began its 4.0 versioning process, with the clear goal of positioning itself as the “one stop shop” for open licensing including open data licensing, and with the only exception of free and open source software licensing.

[26] See [http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/30676](http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/30676)

[27] Even the “First evaluation of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases” (available at http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/copyright/docs/databases/evaluation_report_en.pdf) published by the European Commission in 2005 is quite critical of the sui generis right and finds that the economic impact of such right is, at best, unproven.

[28] For completeness, there were some 2.5 ports that did mention the sui generis right (and/or implicitly included such right amongst neighboring rights), but these may be regarded as national exceptions not governed by a systematic policy.

[29] See the treatment of sui generis database rights policy: https://wiki.creativecommons.org/images/f/f6/V3_Database_Rights.pdf.

[30] For the sake of completeness, this was the most widely publicly discussed reason to develop the UK Open Government License. However, other reasons probably included the desire to use a national branded license (a phenomenon that some open data activist named “license vanity”), and the opportunity to address some standard worries of public officials (e.g., misrepresentation, data protection) with custom language.

[31] For more details, see Morando, F. (2013). Legal interoperability: making Open Government Data compatible with businesses and communities. JLIS. It, 4(1), 441.

B. The Governance of the 4.0 Versioning Process

The international license and legal tool development process is documented by Creative Commons on its official website:[32]

- on the license version page;

- in the Statement of Intent for Attribution-ShareAlike Licenses, which also details the core stewardship activities of CCC; and

- for the 4.0 versioning process, on the 4.0 processes page.

Among other responsibility, the CC General Counsel leads the license versioning and development processes, as well as the development and versioning of other legal tools. As with other relevant processes, the CCC Board also supports the process by providing guidance on overall strategy and strategic decisions on core features of the legal tools.

CCC gathers input from affiliates, the community, and other stakeholders through a variety of means. A public, editable wiki allows anyone to submit issues for consideration, to comment on open matters, and for CCC staff to document decisions and underlying considerations.

The primary discussion forum for proposed changes to the legal tools is the license development list.[33] This list is a moderated, subscriber-based list that is publicly archived. CCC also solicits input directly from its Affiliates on their dedicated email list (accessible to affiliates only). During the 4.0 versioning process, CCC also obtained input via periodic, regional conference calls held in conjunction with the release of each draft. Outcomes from those calls were publicly posted with the corresponding draft.[34]

During the drafting process, CCC also aimed to identify additional stakeholders beyond those represented or contacted by the CC affiliates, including candidates for adopting CC’s tools or adopters who might be affected by the changes. As described by CCC staff: “These stakeholders are identified by staff and by affiliates and their input may be sought through private engagements rather than public consultations (though CC takes pains to document all input and decisions that are made). We believe that different stakeholders have different comfort levels with public engagements for any number of reason—getting their input by whatever means is important as long as we remain transparent about interests at stake and reasons for decisions that are based on private rather than public input.”

As CCC staff members put it, “The increase in participation and our efforts is ostensibly the reason the [4.0 versioning] process took three full years.” Such processes were also conducted at a worldwide scale, thanks to the support of Affiliates and Regional Coordinators.

[32] As one may notice from the links below, it is the “wiki” third-level domain that hosts this part of the CC website, therefore affiliates and other members of the CC community may contribute to the description of these processes—with the exception of the “CC Attribution-ShareAlike Intent” page, which is protected from direct edits. In practice, however, these sections are mainly curated by the CCC staff, and are posted for draft in advance of finalization, as documented by the history of each page on the wiki.

[33] http://lists.ibiblio.org/mailman/listinfo/cc-licenses.

[34] For examples, see https://wiki.creativecommons.org/4.0/Drafts.

1. Final Decisions on the Most Heated 4.0 Drafting Issues

The key development in version 4.0 was the reversal of policy regarding sui generis rights. Although CC was motivated by the best of intentions, the decision to waive sui generis rights created more problems than it solved. After many years of experiencing problems associated with this decision, and with the input of affiliates and other experts in the EU,[35] CCC changed its position, as reflected in the final version 4.0 licenses. In fact, the sui generis right is currently licensed in analogy to copyright, instead of waived. In the end, as CCC staff members put it, “that matter resolved itself, and it is testament to CC that it can change policy direction when it becomes apparent that an existing policy stance is no longer the best policy for the organization.”

Another issue that surfaced most during the 4.0 versioning process concerns the decision whether to define further the meaning of “NonCommercial.” Again, the CC community was divided on this issue. In this case, the CCC staff made the ultimate decision to leave the definition as is in order to maintain the expectations of licensors and licensees. As CCC staff members put it, this is a good example of an agreement to disagree. “Our experience has been that so long as we provide a forum in which all sides can be heard, we engage in a healthy debate and demonstrate an understanding of concerns on all sides, that the community respects decisions that are made by CC[C] in its stewardship capacity.”

[35] As described by CCC staff members, “Creative Commons with some frequency consults with third parties outside the network on both policy and legal matters. This includes consulting with affiliates in their other capacities. CC occasionally engages outside legal counsel to obtain formal opinions on legal issues. This is not because our legal affiliates are not adequate, but because they are volunteers, are time-constrained at times, and are not providing formal legal advice to CC (there is no attorney-client relationship). CC also works closely with other organizations that are experts on issues where we may not have expertise within our network or because of the experts’ prominence on particular issues. For example, during the 4.0 versioning process CC consulted with EFF on the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the crafting of the definition of Effective Technological Measures, because of their unique expertise in the area from both a policy and legal perspective.”

VI. Conclusions and Lessons Learned

The main lesson of the Creative Commons governance model is best summarized by a quotation from the interviewed Creative Commons staff members, Diane Peters and Timothy Vollmer: “Being overly consultative and overly inclusive, even when there is little response, is important to maintaining credibility as an organization. Similarly, transparency is important, as is being willing to admit we don’t have all the answers or always get every decision right. These are important features of a multistakeholder, global organization operating on the cutting edge of legal and policy matters.”