Swiss ComCom FTTH Roundtable

This case study by the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University explores the dimensions of how the Swiss government used a multistakeholder process to organize private sector firms to begin deploying in a coordinated fashion a fiber optic network connected to every home in Switzerland.

Photo: Nick Wheeler (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Photo: Nick Wheeler (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Swiss ComCom FTTH Roundtable

Authors: Urs Gasser, Ryan Budish, David R. O’Brien

Sarah Myers West, Sergio Alves Jr., Alexander Sculthorpe

Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University

Abstract: This case study explores the dimensions of how the Swiss government – in particular, the Swiss Federal Communications Commission (ComCom) and the Swiss Federal Office of Communications (OFCOM) – used a multistakeholder process to organize private sector firms to begin deploying in a coordinated fashion a fiber optic network connected to every home in Switzerland. Although fiber optic connections were available in some areas of Switzerland, telecommunications and cable companies in many regions of the country had not yet upgraded older network infrastructure to fiber or connected it to homes. The large capital investments required, competing interests among stakeholders, and the lack of coordinated efforts to serve common interests were all contributing factors. The Swiss government was eager to see the national infrastructure upgraded, but lacked the formal authority to regulate the fiber optic networks under its communications laws. In lieu of regulation, the Swiss government convened a series of voluntary roundtable meetings between 2008-2012 to achieve a consensus-based solution. The Roundtables, and related technical working groups, attempted to bring together the critical stakeholders and surface the key issues that needed to be resolved. Using Swiss public records, reports, and personal accounts of those directly involved, this case study examines the roles and approaches used in the fiber to the home (FTTH) Roundtables and evaluates the process used as a model of ad hoc, problem solving and distributed governance.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Background

A. Limited Competition Pre-2007

B. Market Disruption in 2007

III. FTTH Roundtables: Improving Coordination Among Stakeholders

A. Why ComCom?

B. The Goals of the Roundtables

C. Beginning the Roundtables

IV. Roundtables in Action

A. The Structure of the Roundtables

B. The Roundtable Meetings

C. Confidentiality

D. ComCom as Mediator?

E. Working Groups

V. Decision Making and Outcomes

A. Use of Consensus

B. Defining Success

VI. Observations on Particular Features

A. Regulation May Not Be Necessary to Compel Participation Where Market Incentives are Sufficiently Strong

B. Participants May View the Value of Transparency Differently

C. Reducing Rules or Procedures Comes With a Tradeoff

D. Separation of Strategic and Technical Domains May Be an Effective Approach to Addressing Complex Issues

E. Skilled Facilitation May Address Issues of Incomplete Representation

F. Ad Hoc Groups May Be Built on Already Established Structures

G. Subject Knowledge May Be an Important Strategic Resource

VII. Conclusion

I. Introduction

In 2008, Switzerland faced a difficult question. High-speed Internet technologies were quickly evolving, but few homes were connected to the next-generation fiber optic technologies and Switzerland’s fiber penetration rate was falling behind that of other countries. At the heart of the issue was how to deploy “fiber to the home” (FTTH) – the last portion of fiber optic cabling necessary to connect homes and buildings to the existing fiber optic network infrastructure. FTTH connections would offer substantial improvement in speed and capacity, paving the way for new, innovative web services in the future. Few regions in Switzerland had FTTH, and deploying it would be a costly investment for private-sector companies, which owned and operated the existing older-generation copper wire connections and had already invested in new technologies that would provide incremental speed improvements in the connections. A number of stakeholders at all levels, including established incumbents, new market entrants, property owners, and others, were also interested in how FTTH deployment was to proceed.

Coordination in Switzerland, however, was complicated by the fact that no government agency had the regulatory authority to compel stakeholders to cooperate or to mandate that they invest in FTTH. Despite that lack of formal authority, it seems that a mix of soft-power and skilled facilitation was able to elicit cooperation among this diverse array of stakeholders and ultimately enable the expansion of FTTH in Switzerland. The effort was led by the Swiss Communications Commission (ComCom), which convened a series ad hoc, distributed, multistakeholder Roundtables over a period of several years. The goal, from the government’s perspective, was to convince stakeholders to make the necessary investments, identify and address issues among and between the stakeholders, and to set the stage for an organized deployment of FTTH in a manner that would maximize its economic benefit while minimizing its disruptive effects.

Using public records, written accounts, and interviews with those directly involved,[1] this case study explores the ways in which these Roundtables operated and identifies some of factors that enabled the roundtables to achieve consensus among its participants in the absence of formal regulatory enforcement authority. The case study begins with a discussion of the background factors that led to the Roundtables, including the telecommunications market in Switzerland and its key actors. The case study then describes the formation and operation of the ComCom Roundtables, and finally assesses some of the strengths and weaknesses of the Roundtables as a means of coordinating the actions of diverse, competing stakeholders.

[1] Due to the small number of people involved in the roundtables, and our small sample of interviewees, we have elected to keep their identities and specific roles private.

II. Background

The events that unfolded in the years prior to the Roundtables are useful for understanding the interests of and challenges facing many of the stakeholders. These years are characterized by shifting power structures within the Swiss high-speed internet industry, new market entrants, changes in technology, regulation or lack thereof, and a desire by government actors for Switzerland to lead in penetration and service.

A. Limited Competition Pre-2007

Switzerland’s telecommunications market is dominated by Swisscom, which was the successor to the formerly state-owned monopoly PTT (Post, Telegraph, Telephone). Switzerland began to transition PTT to a private company beginning in 1997. Today, Swisscom still has vestiges of state control. The Swiss Confederation owns 51.2% percent of the share capital and current law [2] limits private ownership in Swisscom to 49.9%. Its history as a state-owned monopoly placed Swisscom in a privileged position within the market; Swisscom holds a dominant market position in many telecommunications services in Switzerland with 55.3% of market share in broadband and 62% in wireless.[3] By 2012 Swisscom claimed to have the lead in digital TV subscriptions, despite having only entered the market in 2007.[4]

Prior to 2007, Swisscom faced limited threats to its dominance in the telecommunications industry. Although other telecommunications companies were available in the market, they were not significant competitors in several service categories. In the broadband market in particular, its competitors were reliant on Swisscom reselling access to its own network. As ComCom noted in 2007, “in the absence of effective unbundling in the ADSL market, the alternative providers who are still unable to offer anything other than Swisscom’s resale products cannot compete against the historic operator and are falling inevitably – and worryingly – behind.”[5] Accordingly, as of 2007, Swisscom faced little pressure from other telecommunications providers to begin a costly build-out of fiber optic cable.

Swisscom similarly had little threat in 2007 from cable operators. Although Cablecom, Switzerland’s primary cable services provider, has been called “Swisscom’s main competitor,”[6] it appears to have been a fairly week one. As of 2003, cable and DSL broadband were effectively equals in the market. However, by 2007, “Swisscom’s market share (50%) [was] more than twice that of Cablecom (approximately 20%),” leading ComCom to state that “the cable operators appear to exercise insufficient pressure on the broadband market.”[7] Thus, as of 2007 Swisscom faced insufficient competitive pressure to justify an expensive infrastructure investment.

Swisscom was investing in its infrastructure, but not at the level necessary to support FTTH development. As one of our interviewees explained, the traditional model of telecommunication infrastructure improvement reinvests profits from services into incremental growth of the existing network infrastructure; because consumer demand tends to grow slowly, so too does the investment. One interviewee explained that Swisscom was making investments in fiber optics for large businesses, office blocks, and long-distance communication. Additionally, Swisscom deployed fiber optic cables to neighborhoods, reaching as far as street cabinets. But bringing cables “the last mile” into individual homes would have been a difficult and expensive undertaking. According to one of our interviewees, the uncertainty regarding the immediate demand for so much bandwidth and the ability to quickly recover the investment made aggressive FTTH deployment unattractive for telecommunications companies to make solely based on revenue from existing services. Swisscom seemed content to simply pursue the steady technical improvement of their copper-wire based legacy technology.

[2] Swisscom, “Ownership Structure – who does Swisscom belong to?,” http://www.swisscom.ch/en/about/investors/shares/ownership-structure.html.

[3] Yochai Benkler, “Next Generation Connectivity: A review of broadband Internet transitions and policy from around the world,” Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, (February 2010) , pp. 317, 324.

[4] Swisscom, “History: More than 160 years with a finger on the pulse,” http://www.swisscom.ch/en/about/company/history.html.

[5] Swiss Federal Communications Commission, “Swiss ComCom’s Annual Report 2007,” (2007), p. 10.

[6] “Next Generation Connectivity,” p. 315.

[7] “Swiss ComCom’s Annual Report 2007,” p. 10.

B. Market Disruption in 2007

============

Beginning in 2007, the market was disrupted by three changes that spurred a rapid growth of FTTH in Switzerland. These disruptions were: (1) legislation opening up access to Swisscom’s infrastructure, (2) the entry of the utility companies into the market, and (3) the cable providers adopting the DOCSIS 3.0 standard. Together these changes created an environment where the Roundtables became necessary.

The first of these changes was implementation of the revised Law on Telecommunications.[8] This legislation included “local loop unbundling” and “subloop unbundling.” Collectively, this meant that Swisscom would have to offer competitors access to its last-mile infrastructure at reasonable rates. Writing about this unbundling in 2007, ComCom stated “only with access to this copper cable will alternative providers be able to compete with Swisscom’s VDSL offerings and other competitive high-bandwidth products in the future.”[9] Although in hindsight unbundling appears to have been insufficient at generating VDSL competition,[10] in 2007 Swisscom perceived unbundling to be a potential threat to its market position.

The second, and perhaps most significant, market change was the entry of the utility companies into the telecommunications market. Unlike telecommunications companies, Swiss utility companies were in a strong position to invest in FTTH. First, they had the financial resources to support the investment. Many utility companies in Switzerland are publicly held local monopolies that serve a particular geographic area. One of our interviewees described how this arrangement of local monopolies on water, gas and electricity allowed the utilities to marshal the financial resources for a major infrastructure project such as an FTTH deployment. Second, the utility companies needed a high-quality communications network in order to manage “smart meters” located in customer homes. Thus, the utilities needed to make substantial investments in communications infrastructure. Finally, the utilities already owned a series of conduits into homes – water lines, electrical wiring, gar lines, and sewers – and had space in those conduits for fiber cabling.

For all of these reasons, the local utilities began to consider building FTTH and entering the telecommunications market. In 2007, the local utility of Zurich was among the first to announce it would spend CHF 200 million, approximately USD 170 million, to deploy FTTH. Other utilities followed shortly thereafter with similar announcements.[11] According to one interviewee, the utility companies offered a compelling story: this investment would improve service and ultimately make Swiss cities competitive with cities such as New York and London.

The third disruption in 2007 occurred when cable providers began to adopt the DOCSIS 3.0 standard. This standard for cable modems was adopted in 2006, and enabled speeds of 100 Mbit/s.[12] This allowed the cable providers to offer “next generation access” services on par with that of the xDSL standards.[13] According to one of our interviewees, because 90% of Swiss homes were wired for cable service, it meant that cable providers with 100 Mbit/s speed were suddenly a threat to Swisscom’s broadband dominance.

Because of these new threats to its market share, Swisscom found itself in a bind: invest in new, faster technologies or risk losing customers. As one interviewee described, Swisscom was suddenly facing pressure on multiple sides; both the cable providers and utilities could leverage their existing infrastructure to provide faster broadband than Swisscom was offering. Swisscom responded by announcing a rollout of FTTH in parallel to that of the utilities,[14] meaning now multiple stakeholders were poised to begin parallel and uncoordinated massive construction projects across the country.

[8] “Swiss ComCom’s Annual Report 2007,” p. 5.

[9] Id.

[10] Swiss Federal Communications Commission, “Activity Report ComCom 2012,” (2012), p. 14 (“[T]his decline [in unbundled lines] has to be seen in relation to the development of digital television on the fixed network. The ADSL technology is not sufficient for digital television, TV in HD quality needs the higher transmission capacity of VDSL. This requires providers to rely on a Swisscom wholesale VDSL offering in order to benefit from sufficient bandwidth to offer their customers television over IP.”)

[11] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Developments (OECD), “Financing the Roll-out of Broadband Networks,” (June 12, 2014), p. 4, http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2014)17&docLanguage=En.

[12] Greg White, “DOCSIS 3.0 – The road to 100 Mbps,” CableLabs Presentation to the NANOG (2008), https://www.nanog.org/meetings/nanog43/presentations/GWhite_DOCSIS_rev_N43.pdf.

[13] Fibre to the Home Council Europe, Business Committee, “FTTH Business Guide,” (February 2012), http://www.ftthcouncilmena.org/documents/Reports/FTTH-Business-Guide-2012-V3.0-English.pdf.

[14] “Financing the Roll-Out of Broadband Networks,” p. 4.

III. FTTH Roundtables: Improving Coordination Among Stakeholders

With Swisscom, the utilities, and the cable companies suddenly engaging in competition and costly infrastructure construction projects, the risk for disruption was high. One interviewee described how if the parties operated in an uncoordinated fashion, roads would be torn up, put back, and then torn up again, affecting residents and businesses alike. Similarly, landlords would have to negotiate multiple agreements for access to the premises and installations of fiber hardware.[15] Moreover, as one interviewee described, Swisscom’s demand for exclusive rights to the homes in which they built fiber meant that cable providers risked being shutout. Accordingly, Switzerland faced a complex and unpredictable regulatory and business environment.

[15] Swiss Federal Communications Commission, “Interview with Marc Furrer of the ComCom,” (September 1, 2009), http://www.comcom.admin.ch/dokumentation/00442/00775/index.html?lang=en.

A. Why ComCom?

To address this problem, ComCom announced it was convening an ad hoc series of Roundtable meetings to encourage cooperation among the various stakeholders. In addition to concerns about the disruption, described above, one interviewee said that ComCom believed that left to their own devices, the private sector acting in a regulatory vacuum would roll out FTTH in a slow, uneven, and sub-optimal manner. The concern was that competition and a lack of communication amongst all stakeholders would mean poor organization, delays, and a failure to distribute FTTH evenly across Switzerland. An uneven distribution of FTTH could mean that some regions would be underserved. Additionally ComCom was concerned that absent regulation FTTH would be deployed with incompatible technologies, which would lock customers into particular companies and create de facto monopolies. ComCom believed coordination would be necessary to ensure the fiber rollout occurred as quickly and efficiently as possible, while maintaining competition in the marketplace.[16]

At first glance ComCom was ill equipped to deliver such coordination among the stakeholders. Although ComCom had primary responsibility for overseeing the communications market in general, it lacked regulatory authority over FTTH. The Swiss Telecommunications Act did not specify that ComCom had the power to regulate fiber optic networks. This meant that ComCom could not formally compel the stakeholders to join the Roundtables and could not enforce any decisions that emerged from it. Consequently, ComCom’s role was, in the literal sense, limited to that of a facilitator, not a regulator. The other political body that could have taken a lead in regulating the FTTH rollout was the Federal Council – the seven-member body that comprises the federal government of Switzerland. However, the Federal Council chose not to intervene. When ComCom requested that the Federal Council grant it additional regulatory authority, the Federal Council deferred, claiming that it would be premature in light of the unbundling legislation passed in 2007.[17]

Despite its limited regulatory power over fiber optic networks, ComCom was competent in the area of telecommunications policy, and was perceived by at least some participants as having legitimate authority over the field. Arguably this placed ComCom in a better position than other regulatory bodies to lead the Roundtables. Other governmental regulators, such as the Federal Office of Communications (OFCOM), still played a significant supportive role.[18] In its day-to-day responsibilities, OFCOM “prepares everything that the Federal Council and the Federal Communications Commission need to make policy decisions,”[19] and frequently cooperates with ComCom in most regulatory matters.[20] In the Roundtables, OFCOM organized the technically-focused working groups (described below), and provided additional resources and administrative capacity to the leanly staffed ComCom.

Although participation in the Roundtables was voluntary and ComCom lacked specific regulatory powers over fiber optic networks, ComCom was still perceived to have some authority. Other regulators with potential levers of control kept a watchful eye on developments from a background vantage during ComCom’s facilitation. While no specific threats appear to have been made, the Roundtables formed under the looming possibility of regulatory action, which undoubtedly influenced the willingness of stakeholders to participate in the Roundtables. Indeed, one of our interviewees noted that one reason why Swisscom participated in the Roundtables was to avoid regulatory scrutiny. The Competition Commission (ComCo) appears to have played an important role in this regard. As Switzerland’s antitrust regulator, ComCo is responsible for “monitoring dominant companies for signs of anti-competitive conduct,”[21] which it enforces through civil fines. Just one year before the Roundtables were convened, ComCo fined Swisscom Mobile CHF 333 million, approximately USD 372.3 million.[22] ComCo also reviewed the 2010 and 2011 agreements between Swisscom and the utilities that emerged from the Roundtables.[23]

[16] It is important to note that not all interviewees viewed ComCom’s role so charitably. One individual suggested that ComCom was primarily interested in keeping itself relevant in the FTTH telecom space despite a lack of legal authority.

[17] “Next Generation Connectivity,” p. 320.

[18] OFCOM, “Why is OFCOM needed?,” http://www.ofcom.admin.ch/org/00577/index.html?lang=en (“OFCOM’s mission is to guarantee that market forces have full play . . . [and] attends to these matters on behalf of” ComCom.)

[19] OFCOM, “OFCOM as the regulatory body,” http://www.ofcom.admin.ch/org/00598/index.html?lang=en.

[20] “Swiss ComCom’s Annual Report 2007,” p. 14.

[21] Swiss Competition Commission (ComCo), http://www.weko.admin.ch/index.html?lang=en&.

[22] Competition Commission, “Swiss Competition Commission imposes a fine of 333 million Francs on Swisscom Mobile,” Federal Administration News, (February 16, 2007), https://www.news.admin.ch/message/index.html?lang=en&msg-id=10863.

[23] “Financing the Roll-Out of Broadband Networks,” p. 5.

B. The Goals of the Roundtables

ComCom convened Roundtables in response to a particular problem: the lack of coordination in the rollout of FTTH in Switzerland. Prior to 2008, FTTH simply was not a pressing concern to ComCom (or Swisscom for that matter).[24] The Roundtables represent an ad hoc distributed governance group formed in response to the identification of an emerging issue. To address this issue, the stated mission of the Roundtables was to define the framework conditions that would allow coordinated development of the optical fiber network.[25] According to an interviewee who attended the meetings, much of the work of the Roundtables centered around issues of competition in the telecommunications market. However, other key issues covered included the standardization of installations, coordinated network construction, and customers’ rights to carrier selection.

In a broader perspective, the Roundtables served as a discussion platform for industry and regulators. It is important to note that the Roundtables were occurring in parallel with FTTH rollout and the signing of cooperation agreements between the stakeholders.[26] The issues that the Roundtables were addressing were past, present, and future concerns. Accordingly, the Roundtables were not a hurdle that the stakeholders had to clear, but a dialogue that could speed up the process, reduce friction, and ultimately generate better outcomes for both customers and providers.

[24] See “Swiss ComCom’s Annual Report 2007,” p.6, 15 (mentioning FTTH only twice in relation to other European countries).

[25] ComCom, “‘Fibre to the Home’ round table – an initial status report,” (June 10, 2009), http://www.comcom.admin.ch/aktuell/00429/00457/00560/index.html?lang=en&msg-id=29395.

[26] See “Financing the Roll-Out of Broadband Networks,” p. 4; “Next Generation Connectivity,” p. 206-09.

C. Beginning the Roundtables

In 2008, when ComCom convened the first of the Roundtables, it first had to decide who to include in the process. According to one interviewee, ComCom needed to balance between having perspectives and voices at the table so that outcomes would be perceived as legitimate, and having so many voices that consensus would be impossible. The list of participants is not public, but in public statements ComCom and OFCOM asserted that “all the players in the industry (telecommunications companies, electricity providers, cable operators and landlords) joined the effort to define the framework conditions which will allow coordinated development of the optical fibre network.”[27]

According to one interviewee, statements about “all the players” participating may be a bit misleading. Instead, ComCom carefully selected the participants, inviting only the largest actors in the market and those who had already begun making FTTH investments. This excluded a large number of potential stakeholders, including all industry associations and advocacy groups, who were upset that they were left out. Every stakeholder that ComCom invited to the Roundtables accepted; one interviewee speculated that the high acceptance rate was in part because an invitation to join a select group of powerbrokers was viewed as prestigious. Ultimately, only about 16 or 17 individuals attended each meeting of the Roundtables.

Given the selection process and the stakes, the barriers for both entry and exit were fairly high. Not only were the participants to the Roundtable handpicked, but also the main meetings required the attendance of the CEO of the invited company or organization. As one interviewee described, companies were not allowed to send delegates or others in place of the CEO; if the CEO was sick, they couldn’t participate at that particular meeting. Barriers to exit were similarly high. Once a stakeholder accepted an invitation to join the Roundtables, walking away from the negotiations could be perceived as non-cooperative among the relatively small set of players involved in the FTTH deployment. Moreover, walking away from the table would have meant losing a voice in a process in which large financial interests were at stake.

Although many potential stakeholders were not invited to participate directly, ComCom took steps to try to represent their views within the meetings. For example, according to one interviewee, several groups were invited to presentations at meetings in order to ensure that their perspectives or interests would be raised. Additionally, ComCom conducted extensive bilateral, backchannel conversations with all stakeholders, both those participating and not participating in the Roundtables. According to one interviewee, ComCom used the backchannel conversations so that it could identify the concerns of those not present and ensure that the key issues were acknowledged and addressed during each meeting. ComCom also conducted backchannel discussions with those participating to take stock of priorities and issues, and to determine the feasibility of proposed solutions.

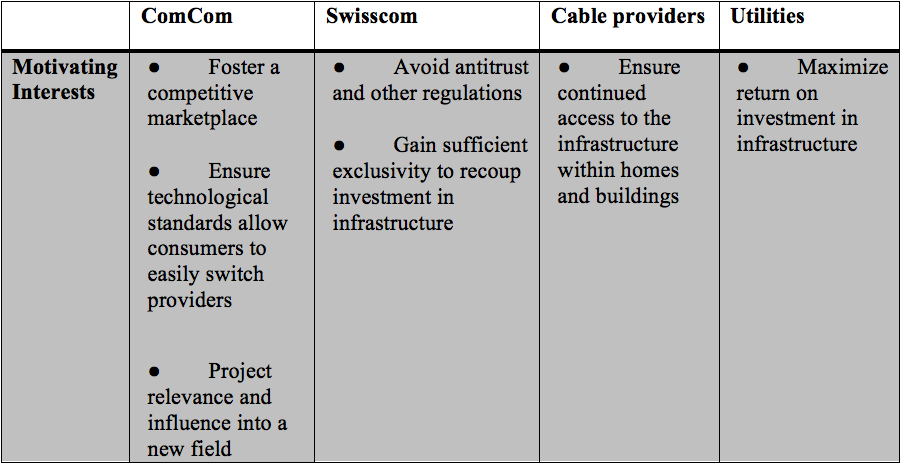

Figure 1: Motivations for Round Table Stakeholders

Figure 1: Motivations for Round Table Stakeholders

[27] OFCOM, “Deployment of Optical Fibre in Switzerland,” http://www.bakom.admin.ch/themen/technologie/01397/03044/index.html?lang=en.

IV. Roundtables in Action

A. The Structure of the Roundtables

Because there were no existing structures to handle coordinating FTTH deployment, and no government agencies with direct regulatory authority over the matter, the Roundtables presented both an opportunity and challenge. The opportunity was in designing a set of ad hoc structures that could directly address specific needs of the FTTH stakeholders. The challenge was in designing the structures so that they would be considered legitimate. ComCom decided to adopt a tiered approach that would separate the high-level policy and strategic questions from the more technical questions. Under this structure, the main Roundtables were limited to CEO-level representatives. The CEO-level group was chaired by the ComCom President Marc Furrer and addressed the policy and strategic questions. Simultaneously, OFCOM organized a set of complimentary working groups that focused on technical matters of a few varieties. For instance, technical working groups addressed interconnection standards, while legal working groups addresses contracting and regulatory technicalities. According to one interviewee, this two-tiered structure allowed technical issues to be resolved quickly, while higher-level participants could negotiate the more political strategy issues.

B. The Roundtable Meetings

The Roundtables met nine times between 2008 and 2012. Despite the significant monetary value of the FTTH deployment, the Roundtables themselves were a relatively minor investment of resources. The meetings were held in Solothurn, a small town north of ComCom’s headquarters in Bern, in an old mansion. According to an interviewee, this location was picked because it was far enough away from the participants’ offices that they would be likely to the stay for the entirety of each meeting instead of departing early to attend other meetings.

ComCom proposed the agenda for each Roundtable meeting. Approximately five days in advance of each meeting, ComCom would distribute an agenda and solicit feedback from the participants. According to one interviewee, the agenda was fairly straightforward in the sense that there was consensus on the issues to be discussed and the order in which they needed to be address. Any additions or alterations to the agenda were generally adopted by consensus as needed.

According to one of our interviewees, the central topic of the Roundtables was resolving the terms of use upon which data would flow through fiber optic cables into the home. The largest point of contention related to open access versus exclusivity. The utility companies largely wanted to adopt an open access model, where they would rent the fiber infrastructure to any service provider, leaving the consumer with equal choice among competitors.[28] In contrast, Swisscom did not want to open up to competitors the fiber it was deploying, as it was forced to do in years prior with copper wire in the local loop unbundling legislation. Thus, Swisscom sought some degree of exclusivity for their services, to ensure that they could justify the substantive investments in infrastructure. Finally, the cable operators generally sought to maintain access to residences and not be shut out by exclusivity agreements between the owners of the fiber and the landlords or homeowners. The Roundtables served as a means for balancing these competing interests.

[28] See “Next Generation Connectivity,” p. 206 (describing the Openaxs coalition “committed to the concept of open access and with the goal to promote fiber-optic networks in general and FTTH in particular based on the principles of fair competition and consumer choice.”).

C. Confidentiality

There were only two rules governing the operation of the Roundtables. One of those rules, already addressed, was that only one person was permitted around the table from each participating organization, and that person must hold a CEO-level position. Any accompanying staff were instructed to wait outside of the room during the meetings. The second rule, according to interviewees, was that none of the participants would talk to the media concerning the content of the discussions; instead, ComCom would act as sole representative of the Roundtables to the public.

In theory both of these rules were in place to enable a free and open discussion, and create an environment where consensus and compromise was possible, without participants needing to seek approval from superiors. Attempting to reach consensus on the coordination FTTH deployment would require the participants to disclose information about their corporate strategy, and accordingly it was believed that a closed-door discussion would best facilitate reaching an outcome. Although using closed-door meetings may have facilitated a more open discussion, according to at least one participant, it came at the cost of perceived legitimacy for those stakeholders who believed their views were not adequately addressed.

D. ComCom as Mediator?

ComCom’s effectiveness as the convener of the Roundtables is a matter of some debate. According to one participant, ComCom viewed the Roundtables as a multi-party negotiation, and assumed the role of neutral mediator trying to facilitate a consensus outcome. To this end, ComCom invested substantial time before and after each meeting in bilateral dialogue with stakeholders, both those participating and not. Although this work was not publicized, according to one perspective, these conversations enabled ComCom to mediate between the various parties. In particular, during these bilateral discussions ComCom could engage in negotiations with stakeholders, identify potential stumbling blocks to consensus agreements, and float proposals with stakeholders to assess their reactions.

Another interviewee, however, suggested that the Roundtables were largely a public relations event that enabled ComCom to appear as though it were influencing deployment of FTTH. For instance, this participant said that the full list of agenda items was rarely covered due to time constraints. Despite the fact that the Roundtables failed to cover many of the agenda items, after each meeting, ComCom would publish a press release highlighting areas of agreement. The participant believed on at least some occasions the press releases claimed successes prematurely. The lack of public documentation from the meetings themselves, combined with the fact that the participants agreed that ComCom would be the sole outlet for information regarding the discussions, make it challenging to independently confirm the accuracy of these statements and the effectiveness of ComCom’s role more generally.

E. Working Groups

As described above, OFCOM supported the Roundtables by managing a series of working groups that focused on the more technical aspects of the Roundtables. The working groups were divided into topical areas, with two working groups dedicated to the infrastructure layer (Layer 1), two working groups dedicated to the services layer (Layer 2), and one for legal issues. As described by OFCOM,[29] the mission of each working group is as follows:

- Working Group L1: Define standards for optical fiber cabling inside buildings

- Working Group L1B: Determine the transfer points in FTTH networks

- Working Group L2: Discuss common points relevant for the industry concerning access to services and L2, particularly enabling access for alternative providers who do not have their own network

- Working Group L2B: Establish a universal platform for the ordering of, or migration to, optical fiber and transport services

- Working Group 3: Draw up recommendations for arranging contracts between network operators and building owners

Generally, each working group created a set of recommendations or proposed standards that address its assigned topic. In most cases, the documents included an executive summary, introduction, definitions, scope, topic specifics, recommendations, next steps, graphs or other visual aids, and references. Each working group had the flexibility to shape their guidelines to fit their specific mission.

Beyond simply providing a targeted forum for resolving less strategic issues, the working groups offered two additional benefits. First, they provided a venue for participation for some of those who were not invited to the CEO-level Roundtables. Second, the technical guidelines and model contracts produced by the working groups are best practice documents that can serve as resources for others, both in Switzerland and beyond, about possible approaches to coordinating deployment of FTTH.

[29] Federal Office of Communications, “FTTH Working Groups,” http://www.bakom.admin.ch/themen/technologie/01397/03044/03046/index.html?lang=en.

V. Decision Making and Outcomes

A. Use of Consensus

Ultimately, the Roundtables led to the consensus adoption of a “four-fiber” solution, which was originally proposed by Swisscom. Consensus was a key aspect of the Roundtables both by design and out of necessity. According to one interviewee, ComCom’s lack of regulatory authority was, ultimately, a benefit. Because there was no actor that could enforce the decisions of the Roundtables, any outcomes would need the support of all of the participants in order to be successful. Today, Switzerland has deployed FTTH far faster than many other European countries, in part because while other countries have relied upon regulation to force FTTH build-out, Switzerland’s rollout was done with the support of all key stakeholders.

Although consensus was important, not all of the Roundtable participants shared equally in every decision. For example an interviewee noted that when the Roundtables addressed the issue of cost sharing, Swisscom and the utilities were the primary parties to the decision, with the cable companies playing a more minor role because they were building new infrastructure. Our interviewees did note that every participant participated in good faith, even when disappointed with a particular outcome. Thus, the Roundtables made decisions using consensus, but not every issue required the full support or involvement of every party.

B. Defining Success

ComCom’s public statements assert that the Roundtables were successful in achieving its stated mission and goals, though our interviews indicated some skepticism. In its press releases, ComCom claimed the following successes:[30]

- The network architecture was created in a coordinated manner, encouraging competition without duplication.

- Uniform technical standards were established, including the four-fiber model proposed by Swisscom.

- A model contract was made available for property owners and networks operators governing legal and financial aspects of FTTH installation.

The four-fiber model that the parties adopted was particularly significant as a mechanism for reconciling the stakeholders’ divergent objectives of open access (the utility companies) and exclusivity (Swisscom). Under this model, multiple lines of fiber would be deployed to each home, with the costs and uses shared between the participants. For instance, if Swisscom built FTTH in a city, with investment from the local utility, Swisscom would own all four fibers and get exclusive access to one or two fibers, the utility would have an indefeasible right to use a fiber, and the remaining fiber could be rented wholesale to other competitors. Thus, Swisscom had exclusive right to a fiber, and the utilities were able to offer open access services on their fibers.

By January 2012, ComCom and the other Roundtable participants agreed that the meetings were no longer necessary. According to one interviewee, the Roundtables were never formally concluded, and the option remains to reconvene if the parties believed that the agreements were not working as intended, or if additional coordination became necessary.

By many metrics, the rollout of FTTH in Switzerland appears to have been quite successful. According to ComCom’s 2013 Annual Report,[31] 750,000 homes and businesses now have fiber access in Switzerland, and that number is expected to grow by 200,000 per year. Additionally, all providers have access to the network on equal terms via the open access fibers and at multiple levels of the network, and users with fiber have the ability to choose their providers.

Despite impressive numbers of FTTH deployment, it is not clear to what extent the success is attributable to the Roundtables. For example, although the four-fiber model was agreed to as part of the Roundtables, it was not initially proposed in the Roundtables. In fact, Swisscom announced this model in 2008, when the Roundtables were just beginning.[32] The first Roundtable press release to mention a multiple fiber model was in October 2009.[33] Consequently, it is difficult to know whether widespread adoption of the four-fiber model was an outcome of the Roundtables, or simply a solution that would have occurred in the absence of any intervention.

More generally, it is not clear that the four-fiber model has worked as a mechanism for generating competition in the marketplace. According to one participant, the open access fibers that the utilities control are largely dark (unused). This individual speculated that one reason why the utilities have been unable to rent their fiber is because they failed to sufficiently grasp the telecommunications market. Since the utilities are all local, any service providers who wanted to use the open access fiber would have to negotiate separate agreements with each locality in which they want to offer service. In contrast, in most regions Swisscom controls two fibers, and can offer the excess capacity on a national scale – an offer that is more appealing than negotiating hundreds of separate agreements.

Another possibility for why the utilities companies have been unable to profit from their fiber was the uneven leverage of the participants during the Roundtables. According to one participant, Swisscom and the cable providers were more successful at representing their interests and obtaining their desired results than the utilities, who often lacked necessary technical knowledge. In some cases the utility representatives to the Roundtables did not understand technical operation of a fiber network, making it difficult for them to advocate on behalf of their interests.

Not all of the participants had such a pessimistic interpretation of the events. One interviewee, suggested that the FTTH rollout is still in its “early days.” In the long run, the participant believed that the fiber would be used because the need for high-speed bandwidth would only continue to increase. Moreover, the fact that the deployment and cooperation was accomplished without government regulation was a success in itself, and according to the participant, may be why FTTH deployment has occurred far faster than in other European nations.

All of our interviewees agreed that the Roundtables were useful for fact-finding, convening stakeholders, and defining regulatory standards. From here, however, perspectives diverge on other topics. One view was that the Roundtables could have served as a valuable input for the development of a law or regulation amenable to all players; in the absence of such a law it left an unregulated environment that overwhelmingly benefits the market dominant Swisscom. Another view, however, was that all parties benefited from the outcome of the Roundtables and that regulation and government intervention would have only served to reduce the incentives for FTTH development in Switzerland.

[30] ComCom, “Fiber to the Home – Press Releases Regarding FTTH,” http://www.comcom.admin.ch/themen/00769/index.html?lang=en.

[31] ComCom, “Activity Report ComCom 2013,” (2013), http://www.comcom.admin.ch/dokumentation/00564/index.html?lang=en.

[32] Swisscom, “Into the fibre-optic future with ‘fibre Suisse’,” Press Release, (December 9, 2008), http://www.swisscom.ch/de/about/medien/press-releases/2008/12/20081209_01_Mit_fibre_suisse_in_die_Glasfaserzukunft.html.

[33] ComCom, “Fibre to the Home” round table – an initial status report, (October 6, 2009), http://www.comcom.admin.ch/aktuell/00429/00457/00560/index.html?lang=en&msg-id=29395.

VI. Observations on Particular Features

It is possible to assess some aspects of the Roundtables as a means of deploying FTTH in Switzerland. As the discussion above indicates, it is perhaps premature to determine whether the deployment of FTTH in Switzerland was itself a success, but based upon interviews with participants and a review of the process of convening the Roundtables, it is possible to make some observations with regards to the elements that worked better and worse than others, as well as offer a considerations that could be instructive.

A. Regulation May Not Be Necessary to Compel Participation Where Market Incentives are Sufficiently Strong

The stakeholders that participated in the Roundtables did not do so because they were forced by law to attend. Instead, they appeared to recognize the opportunity that the Roundtables offered, particularly as a means for reaching agreement on cost-sharing, and reducing duplication of effort. Additionally, our interviews suggested that Swisscom saw the Roundtables as a means to avoid antitrust regulation, suggesting that in this case the potential for regulation was just as effective as regulation itself.

B. Participants May View the Value of Transparency Differently

Some participants felt that the Roundtables were opaque. While the decisions were published via press releases and working group outputs, the participant selection process, the identities of the participants, and the decision-making processes were not public. Others, however, viewed the lack of transparency as a necessity in order to reach best outcomes from a policy standpoint.

C. Reducing Rules or Procedures Comes With a Tradeoff

The convening and operation of the Roundtables were fairly informal. In part this seems to be a function of the fact that there was there was no precedent to follow from the creation of similar organizations in Switzerland. According to our interviews, the informality also seemed to follow from a mix of ComCom trying to ensure that the stakeholders could define through consensus the role of the Roundtables, and ComCom lacking the authority to impose a definition in the first place. Regardless of the reason, the results of this informality were mixed according to participants. Some felt that the informal approach provided efficiency and allowed the stakeholders to have ownership over the process, but others felt that the informality enabled the more experienced stakeholders to take advantage of the utilities, because the rules offered no protections or constraints on power.

D. Separation of Strategic and Technical Domains May Be an Effective Approach to Addressing Complex Issues

The Roundtable was distributed due to the fact that it separated the high-level strategic issues, addressed by the CEOs, from the more technical matters, addressed by the working groups. These two distributed elements were cooperative but were run by two separate entities, providing some independence and avoiding a bottleneck of decisionmaking. OFCOM, which managed the working groups, declined to be interviewed for this case study; further research would explore in more detail how OFCOM managed and coordinated the working groups, particularly with respect to the decisions emerging from the CEO-level sessions.

E. Skilled Facilitation May Address Issues of Incomplete Representation

Although ComCom invited the stakeholders that it perceived as necessary, it did not include all individuals and groups that had a stake in FTTH deployment. For example, industry associations, community or neighborhood groups concerned about construction noise or environmental factors, and landlords and homeowners associations were not invited. According to an interviewee, the smaller group enabled faster decisionmaking and increased the chances of reaching consensus. An interviewee suggested that many who were left out of the process were initially unhappy; the Chair of the Roundtables, ComCom’s Marc Furrer, apparently took steps in order to engage bilaterally with all of these excluded stakeholders, and then brought their perspectives back to the Roundtables.

F. Ad Hoc Groups May Be Built on Already Established Structures

Prior to the Roundtables, ComCom and OFCOM had an existing formal relationship. Although the Roundtables and affiliated working groups were new, the idea of the two organizations working in tandem on telecommunications issues was not.

G. Subject Knowledge May Be an Important Strategic Resource

According to one participant, despite significant monetary resources, the utility companies struggled to effectively advance their interests in a forum dominated by stakeholders with extensive experience in the telecommunications industry. Accordingly, financial resources may not be sufficient to ensure meaningful participation, if such resources are not used to mitigate a knowledge deficit.

VII. Conclusion

The Roundtables are an interesting example of an ad hoc, distributed governance organization. In particular, ComCom faced the challenge of achieving consensus among its participants and doing so in the absence of formal regulation enforcement authority. Without conducting more empirical research, it is perhaps not possible to conclude that the Roundtables caused the FTTH deployment in Switzerland to be successful. That said, the Roundtables do provide some helpful insights into governance models. For example, the Roundtables are particularly informative on the topics of mapping issues to the correct stakeholders and solutions, the role enabling organizations such as technical experts can play in developing policies, and coordination between actors at both national and local levels.

The Roundtables highlight the challenge of matching governance problems with the right organizations, experts, networks, and governing bodies/entities best able to develop legitimate, effective and efficient solutions. In this example, despite the absence of any formal authority to regulate FTTH, ComCom took the lead in creating a forum to address the issue. The financial self-interest of the parties, the prestige of the dialogue, and the network of regulatory bodies operating in the background, created an environment in which all stakeholders that ComCom invited joined in willingly and contributed meaningfully. That said, ComCom did not invite all stakeholders to participate in the Roundtables; it exercised its discretion in mapping the issue onto the appropriate stakeholders. Although this decision was not initially received well, it appears that most parties were mollified through bilateral conversations with ComCom, or through seeing their views represented in either other parties or the final outputs.

The Roundtables also highlight the important role that expert enablers can play in the formation of policy. Enablers are often organizations or resources that allow governance groups to quickly access information and expertise that can guide the workings of the group. For example, enablers may take the form of forums and dialogues (which facilitate broad engagement), expert communities (which facilitate targeted engagement), and capacity development and toolkits (which facilitate empowered engagement). In the Roundtables, the work of CEO-level discussions were complemented through OFCOM’s working groups, which were designed to facilitate the targeted engagement of experts in technical and legal matters related to FTTH deployment.

Finally, the Roundtables highlight the importance of coordination between local and national entities in order to coordinate decisionmaking and lower friction. The Roundtables involved diverse group of players spanning the local, cantonal, and national levels, which represented a variety of horizontal and vertical market players, in coordinating a massive national infrastructure project. As noted at the beginning of this case study, one of the sparks that made the Roundtables necessary was a quintessentially local decision: local utility companies deciding to invest in local infrastructure projects. However, all players – both local and national – recognized the opportunity that coordination could play in improving outcomes and lowering costs.

From a research perspective, a key unanswered question remains the counterfactual question of what would have occurred with Switzerland’s FTTH deployment had the Roundtables not provided an opportunity for coordination? Would the parties have entered into bilateral coordination in the absence of the Roundtables? Would the deployment of FTTH have been more expensive, slower, or disruptive? Would all of the stakeholders’ views been similarly represented? Only by trying to piece together that alternative scenario would it be possible to fairly evaluate the individual decisions made in the context of the Roundtables. Although it is impossible to reconstruct such a counterfactual, further research would benefit from additional interviews, especially with those who did not attend the Roundtables.