Towards a Cyber Security Policy Model – Israel National Cyber Bureau (INCB) Case Study

This case study by the Haifa Center of Law and Technology (HCLT), University of Haifa Faculty of Law follows the creation of a cyber security policy model at the national level. It uses Israel’s recently established National Cyber Bureau (INCB) as a case in point and offers a cross-section comparison between leading cyber security national policies of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan and the Netherlands.

.

.

Towards a Cyber Security Policy Model – Israel National Cyber Bureau (INCB) Case Study

Author: Daniel Benoliel

Haifa Center of Law and Technology, University of Haifa Faculty of Law

Abstract: This case study examines the elements of the creation of a cyber security policy model at a national level. It uses Israel’s recently established National Cyber Bureau (INCB) cyber command funneled by its national cyber policy as a case in point. In so doing the brief offers a cross-section comparison between leading cyber security national policies of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan and the Netherlands. It further introduces comparable policies including the balancing of cyber security with civil liberties, cyber crime policy, adherence to international law and international humanitarian law, forms of regulation (technological standards, legislation, courts, markets or norms) and prevalent forms of cooperation (intra-governmental, regional, public-private platform (PPP) and inter-governmental cooperation).

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Mission and Function

III. The Positive Framework

A. Cyber Security Definitions

B. Models of Cooperation Over Cyber Security

1. Inter-Governmental Cooperation

2. Regional Cooperation

3. Public-Private Platform (PPP)

4. Economics of Information Security Considerations

5. Administrative Responses to Cyber Crises

6. Linking International Cyber Security Policy to Domestic Law

IV. A Cross-Section Comparison

I. Introduction

This policy brief takes a descriptive approach, describing and explaining the characteristics and behaviors of chief stakeholders in Israel’s cyber security policy, including the Israeli government, the recently established Israeli National Cyber Bureau (INCB),[1] and secondary stakeholders—the intermediaries indirectly intertwined with Israel’s cyber policy—such as local academia and cyber industry. On a broader scale of relevancy this policy brief offers a comparison of Israel’s cyber security policy with the advanced cyber security policies of additional countries. Lastly, this brief describes the cyber security standpoints of multiple international stakeholders, including the NETMundial network as well as other related NGOs, standard setting organizations (SSOs), and international organizations such as the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union.

Recent revelations about the United States National Security Agency’s (NSA) clandestine mass electronic surveillance data mining projects raised a public debate worldwide over the legality of governmental compliance with democratic principles.[2] From a legal policy perspective, designing the nooks and crannies of cyber security is challenging for two decisive reasons. First, the field is largely shrouded with secrecy and over classification. Second, the traditional major stakeholders in the field are national defense and intelligence organs.

This excessive secrecy in the Israeli case and elsewhere is already burdensome in current policy initiatives.[3] Not surprisingly, the original attempts to regulate cyber security for the private sector started with—and are still predominantly restricted to—technological standard setting and governmental-industry cooperation therein. To date, four such endeavors are most prevalent. These are the highly popular International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) standards ISO 27001, which appeared as early as 2005,[4] and ISO 27002[5]—two cyber security standards offering ISO/IEC voluntary certifications for complying businesses. In addition, one should mention the Information Security Forum’s (ISF) Standard of Good Practice for Information Security (SoGP), which covers a spectrum of information security arrangements to address business risks associated with information systems,[6] the Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM) best practices in software security,[7] and lastly the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) best practices for cloud computing.[8] Against this backdrop of technical orientation towards cyber security, the focus has gradually shifted onto other stakeholders interested in Internet governance. Such stakeholders typically preside within academia, international non-governmental initiatives, and governments. To date, numerous governments have already taken on this initiative while offering the most advanced sets of cyber security policies. These are noticeably the United States,[9] the United Kingdom,[10] Canada,[11] Japan,[12] Germany,[13] the Netherlands,[14] and Israel’s establishment of an Israel National Cyber Bureau (INCB) in 2011. These national initiatives have also served to establish cyber security threats as predominantly national rather than merely global or international issues.[15] This policy brief focuses on the national level within this natural regulatory flow.

Other stakeholders have also begun initiating equivalent policies. To mention but a few, the NETmundial platform noticeably offers a vibrant bottom-up NGO-based alternative.[16] This platform directly establishes security as one of its seven principles for Internet governance: “Security, stability and resilience of the Internet should be a key objective” and elsewhere “Effectiveness in addressing risks and threats to security and stability of the Internet depends on strong cooperation among different stakeholders.”[17] Similarly, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has been discussing cyber security issues for numerous years, offering yet another multinational discussion platform. To illustrate, at the OSCE Summit held in 2010 in Astana, Kazakhstan, the Heads of State and Government of the 56 participating States of the OSCE underlined that “greater unity of purpose and action in facing emerging transnational threats” must be achieved, while proposing an international “security community.”[18] The Astana Commemorative Declaration mentions cyber threats as one of the significant emerging transnational threats that bridges the north-south divide between developed and developing countries.[19] Yet the OSCE Summit has not yielded more concrete cyber security recommendations to date.

Lastly, a landmark decision recently took place at the United Nations (UN). For the first time in 2013 a group of governmental experts from fifteen member states agreed to acknowledge the full applicability of international law and state responsibility to state behavior in cyberspace.[20] That is, by extending traditional transparency and confidence-building measures, and by recommending international cooperation making information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure more secure against cyber threats worldwide. However, the decision has not yet become international law and is still nonbinding.

The issue of information security has been on the United Nations agenda since the Russian Federation first introduced a draft resolution in the First Committee of the UN General Assembly in 1998.[21] Since then, there have been annual reports by the Secretary-General to the General Assembly with the views of UN member states on these issues. There have also been three Groups of Governmental Experts (GGE) that have reviewed present and future cyber threats and cooperative measures.[22]

Against the backdrop of these initiatives, this policy brief offers a comparative review of Israel’s National Cyber Bureau (INCB), established in 2011. The brief may ultimately assist in constructing a comprehensive national cyber security policy model partially based on Israel’s example, as well as those of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the Netherlands.

One question remains: why Israel? Two significant reasons come to mind. First, Israel’s cyber defense apparatus is world-renowned and considered one of the top programs globally. To illustrate, an international comparative study of twenty-three developed countries put together by Brussels-based think-tank Security & Defense Agenda (SDA) as part of its cyber-security initiative recently awarded Israel with a top grade on “cyber defense,” alongside Sweden and Finland.[23] Yet unlike these two Scandinavian countries, Israel sees approximately one thousand cyber attacks every minute.[24] Second, according to Israel’s National Cyber Bureau, Israel remarkably exports more cyber-related products and services than all other nations combined, apart from the United States.[25] Both its technological prominence and this global market dominance have turned Israel into a global leader in the field and an excellent evolving working example.

Part A introduces the Israeli National Cyber Bureau initiative and the Israeli government’s underlying recommendations. Part B offers a cross-sectional policy comparison between five leading national cyber security policies: those of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the Netherlands. Finally, the conclusion identifies observations from the comparison of different national approaches, with a specific focus on the facilitation of academia-government cooperation in cyber security policy models.

[1] This descriptive approach corresponds with Donaldson & Preston's Multistakeholder theory. See Thomas Donaldson, and Lee Preston, “The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications,” Academy of Management Review vol. 20(1) 70 (1995) (arguing that the theory has mutually supportive facets, which are descriptive, instrumental, and normative).

[2] A key example is the PRISM project. Prism gathers Internet communications derived from demands made to Internet companies such as Yahoo!, Inc. It does so under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 in order to yield any data that counterparts court-approved search terms. See Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani, “NSA infiltrates links to Yahoo, Google data centers worldwide, Snowden documents say,” The Washington Post, October 30, 2013.

[3] Lior Tabansky, The Chair of Cyber Defense, “Yuval Ne’eman Workshop for Science, Technology and Security Tel Aviv University Israel,” Article no III.12 (January 2013), at 2, http://sectech.tau.ac.il/sites/default/files/publications/article_3_12_-_chaire_cyberdefense.pdf. In an interview with Mr. Tal Goldstein (on file with author) from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau on 21 September 2014, it was further emphasized that to a large extent commercial enterprises themselves withhold their cooperation with INCB cyber defense organs due to commercially-related secrecy concerns.

[4] ISO, “An Introduction To ISO 27001 (ISO27001),” http://www.27000.org/iso-27001.htm (described as “specification for an information security management system (ISMS)”).

[5] ISO, “Introduction To ISO 27002 (ISO27002),” http://www.27000.org/iso-27002.htm (offering “guidelines and general principles for initiating, implementing, maintaining, and improving information security management within an organization”).

[6] See The Information Security Forum (ISF), “Standard of Good Practice for Information Security (SoGP),” https://www.securityforum.org/tools/sogp/.

[7] The Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM) is an open framework to help organizations formulate and implement a strategy for software security. The building blocks of the model are the three maturity levels defined for each of the twelve security practices. These define a wide variety of activities in which an organization could engage to reduce security risks and increase software assurance. Common Assurance Maturity Model (CAMM), “Software Assurance Maturity Model: A guide to building security into software development Version—1.0,” at 3, http://www.opensamm.org/downloads/SAMM-1.0.pdf.

[8] Cloud Security Alliance (CSA), “Security Guidance for Critical Areas of Focus in Cloud Computing,” (3rd ed., 2011), https://downloads.cloudsecurityalliance.org/initiatives/guidance/csaguide.v3.0.pdf. The CSA’s best practices cover potential legal issues when using cloud computing. These include protection requirements for information and computer systems, security breach disclosure laws, regulatory requirements, privacy requirements, international laws, etc.

[9] See generally, Barack Obama, “Executive Order—Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity,” February 12, 2013; The White House, “Presidential Policy Directive—Critical Infrastructure and Resilience,” February 12, 2013 (PDD-21); H.R. 3696, 13th Congress 1st Session, “National Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure Protection Act of 2013”; U.S Department of Homeland Security, “NIPP 2013: Partnering for Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience,” Barack Obama, “International Strategy For Cyberspace: Prosperity, Security, and Openness in a Networked World,” The White House (May 2011); National Infrastructure Advisory Council, “Critical Infrastructure Partnership Strategic Assessment: Final Report and Recommendations” (October 14, 2008); The White House, “Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7: Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization, and Protection,” (December 17, 2003) (hereafter “HSPD-7”); The White House, “Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-63,” (May 22, 1998); White House, “Presidential Decision Directive 63: Policy on Critical Infrastructure Protection” (1998); The President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection (PCCIP), “Critical Foundations: Protecting America’s Infrastructures,” Washington, October 1997. PCCIP does not exist today. Its functions have been reallocated per HSPD-7.

[10] For Great Britain’s 2009 policy initiative, see UK Cabinet Office, Cyber Security Strategy of the United Kingdom: Safety, security and resilience in cyber space (London: The Cabinet Office, CM 7642, June 2009), http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm76/7642/7642.pdf.

[11] See Government of Canada, Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy for a Stronger and More Prosperous Canada, (2010), http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/cbr-scrt-strtgy/cbr-scrt-strtgy-eng.pdf.

[12] Information Security Strategy for protecting the nation (2013). Earlier the Japanese Information Security Policy Council released a strategy. See Information Security Strategy for Protecting the Nation, (May 11, 2010), http://www.nisc.go.jp/eng/pdf/New_Strategy_English.pdf.

[13] See Federal Ministry of the Interior, Cyber Security Strategy for Germany (February 2011), https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/BSI/Publications/CyberSecurity/Cyber_Security_Strategy_for_Germany.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

[14] See National Cyber Security, “Strategy 2: From awareness to capability” (2013). See also Ministry of Science and Justice, The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011).

[15] Brigid Grauman, Cyber-Security: The Vexed Question of Global Rules: An Independent Report on Cyber-Preparedness around the World, edited by Security & Defence Agenda (SDA) and McAfee Inc. Brussels: Security & Defence Agenda (SDA), 2012 [hereafter, “the Security & Defence Agenda (SDA) report”], at 66-67.

[16] The NETmundial platform is a voluntary bottom-up, open, and participatory process involving thousands of people from governments, private sector, civil society, technical community, and academia worldwide on Internet governance ecosystem. See Geneva Internet Platform, “GIP Exclusive Coverage of NETmundial,” http://giplatform.org/events/netmundial.

[17] NETmundial Multi stakeholder Statement (April, 24th 2014), at 5, http://netmundial.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/NETmundial-Multistakeholder-Document.pdf (defined as one of NETmundial’s seven principles, titled: “Security and stability and resilience of the Internet”). The statement is a result of NETmundial’s first conference held in Sao Paulo, Brazil between 23-24 April 2014.

NETmundial’s “Roadmap for the Further Evolution of the Internet governance ecosystem” Part (2)III(1)(a) (titled: “Security and stability”) in part (2) dealing with specific Internet governance topics—further reiterates international cooperation “on topics such as jurisdiction and law enforcement assistance to promote cyber security and prevent cybercrime.” See NETmundial, “Roadmap for the Further Evolution of the Internet Governance Ecosystem,” http://content.netmundial.br/contribution/roadmap-for-the-further-evolution-of-the-internet-governance-ecosystem/177.

[18] The Astana Commemorative Declaration: Towards a Security Community (3 December 2010), http://www.osce.org/cio/74985?download=true.

[19] Id. at Article 9.

[20] See UN General Assembly, Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, A/68/98, June 24, 2013.

[21] The General Assembly Resolution was adopted without a vote as A/RES/53/70.

[22] A first successful GGE report was issued in 2010 (A/65/201). In 2011 the General Assembly unanimously approved a resolution (A/RES/66/24) calling for a follow-up to the last GGE. See, The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), Fact sheet, Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, http://www.un.org/disarmament/HomePage/factsheet/iob/Information_Security_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

[23] The Security & Defense Agenda (SDA), “Cyber-Security: The Vexed Question of Global Rules,” Report, (30 January 2012), 66-67.

[24] Id. at 66. In fact, different to the experience of most countries with advanced cyber security policies, Israel’s one did not evolve in response to civil threats i.e., cyber crime but instead it reacted mostly to national security considerations due to the country’s notable geo-political security challenges. See also Interview with Mr. Tal Goldstein from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau, supra note 2.

[25] See Barbara Opall-Rome, “Israel Claims $3B in Cyber Exports; 2nd Only to US,” DefenseNews, June 20, 2014, http://www.defensenews.com/article/20140620/DEFREG04/306200018/Israel-Claims-3B-Cyber-Exports-2nd-Only-US (last year Israel sales reached $3 billion which make approximately 5 percent of the global market).

II. Mission and Function

Israeli cyber security policy was established based on two major official milestones. The first was the 2010 “National Cyber Initiative,” which aimed for Israel to become a top five global cyber superpower by 2015.[26] The second milestone, coming after years of departmental activities in various branches, was the Government of Israel’s Government Resolution No. 3611 as of August 7, 2011, which adopted recommendations for the “National Cyber Initiative.”[27]

At the core of these two initiatives stood the establishment of the Israel National Cyber Bureau (INCB) in the Prime Minister’s office, reporting directly to the Prime Minister.[28] The Bureau’s mission is to serve as an advisory body for the Israeli Prime Minister, the government, and its committees on national policy in the cyber field and to promote implementation of such policies.[29] The decision to create the INCB ended a year-long struggle among different government stakeholders, including the Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet), vying for responsibility over the country’s cyber security apparatus.[30]

The National Cyber Bureau’s mandate is threefold. The first is to defend national infrastructures from cyber attack.[31] This aspect is not restricted to traditional law enforcement deterrence approaches, as it also includes preventative measures.[32] The second mandate is advancing Israel as a world-leading center of information technology based on the country’s high technological advantage.[33] The third mandate is to encourage cooperation between academia, industry and the private sector, government offices and the security community, respectively.[34]

These broad policies were further detailed within the Israel’s government Resolution No. 3611 in three ways. The Resolution’s first mentioned decision and its raison d’être was officially establishing a National Cyber Bureau in the Prime Minister’s Office.[35] The resolutions further calls on the government to establish responsibility for dealing with the cyber field, albeit broadly.[36] Addendum B to the Resolution offers a model description of responsibilities, incorporating a Head Bureau position,[37] Steering Committee,[38] and related administrative working procedures.[39] The third decision set forth by the Resolution was to advance defensive cyber capabilities in Israel, and to advance research and development in cyberspace and supercomputing.[40] Numerous concrete policies were then detailed by the Resolution. These can be categorized as educational recommendations, policy compliance-related recommendations, and strategic recommendations.

To begin with, the Bureau’s educational recommendations proactively identify and mitigate specific cyber security intimidations. The Bureau is consequently tasked with devising “national education plans,”[41] commonly aimed at “increasing public awareness” of cyber threats.[42] Similar to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO),[43] the United States Pentagon’s Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM),[44] Germany,[45] United Kingdom,[46] and Finland,[47] the Israeli Cyber Bureau is said to coordinate national and international exercises,[48] as well as cooperation with parallel bodies abroad.[49]

Secondly, the Resolution sets forth numerous recommendations over policy compliance. These recommendations essentially proffer tailored low-latency policy checkpoints. The Bureau henceforth is set to determine a yearly “national threat of reference,”[50] publish comparable ongoing “warnings”[51] and “preventive practices.”[52]

A national cyber situation room was put in charge of the bureau’s early warning apparatus. The facility conducts ongoing national assessment among various essential civil and security and defense organizations while constituting a first national defensive layer for the entire country’s administration. The national cyber situation room directly reports to INCB’s central command. One telling occasion illustrates the cyber situation room’s contribution. During Operation Pillar of Defense launched by Israel on November 14, 2012 against the Hamas-governed Gaza Strip, a massive overseas cyber attack was carried out against Israel. It included targeted distributed denial of services, the defacement of Israeli websites, and the publication of citizens’ data.[53] As INCB later announced, during the attack no publication of leaked data on any notable or potentially highly damaging scale occurred, largely because of the newly initiated cyber situation room.[54]

The National Cyber Bureau is said to further advance coordination and cooperation between governmental bodies, the defense community, academia, industrial bodies, business, and other bodies relevant to the cyber field.[55] One pivotal illustration demonstrates the organizational constraints with which the INCB operates in the midst of competing stakeholders. The body in Israel responsible for preventing cyber attacks on national infrastructure is the Shin Bet security service. The service also oversees the Israel National Information Security Authority (NISA).[56] NISA is in charge of supervising and warning local governmental and private stakeholders with respect to defending against cyber terror and information security. NISA is further in charge of identifying and preventing cyber attacks over nationally labeled sensitive infrastructure, such as the Bank of Israel, the Israel Securities Authority, the Israel Electric Corporation, Israel Railways, and the Mekorot water company.[57] INCB is not directly responsible for NISA’s preventive activity but instead presumably is able to coordinate its activity vis-a-vis the Prime Minister at large. Surely, other cooperative initiative bear a more independent stand by INCB.

INCB conveniently categorizes its projects in three ways. These are (1) the development of national cyber security infrastructure, (2) the development of human capital and, finally, (3) the development of cyber defense (per the above mentioned national cyber security situation room). INCB has thus far initiated three national security-related projects with Israel’s Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS), the Israeli Ministry of Defense, and Israeli academics. All involve a multistakeholder apparatus, albeit largely local and national. The first of the three is INCB’s cooperation with Israel’s Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) in the Ministry of Economy. In a project called KIDMA (per the initials of the phrase “the promotion of cyber security R&D” in Hebrew), the Chief Scientist has adopted preferential policy for INCB’s R&D projects. In compliance with INCB’s commitment to the promotion of cyber security R&D, the KIDMA is officially aimed at promoting entrepreneurship within this field, while preserving and increasing Israel’s competitive edge in cyber security world markets.[58] In a program that started in 2013, the Chief Scientist endowed the program with 80 million new Israeli shekels (approximately 22 million US dollars) for 2013-2014.[59] A second national cyber security infrastructure project initiated by INCB was a 2012-2013 two-year collaboration with the local national security apparatus. Together with the Israeli Ministry of Defense’s Research Authority, Development of Ammunition, and Technological Infrastructure (MAFAT), these two institutions have allocated a sum of 10 million Israeli new shekels (approximately USD 3.5 million) to a project called MASAD (per the initials of the term “Dual Cyber R&D” in Hebrew).[60] This civil security project approaches cyber security challenges in two ways. It similarly was endowed with 32 million new Israeli shekels (approximately USD 10 million) for the years 2012-2014 and is specifically aimed at fostering academic research in the field.

A third national cyber security infrastructure project was initiated with university-based cyber security research centers. INCB has to date partnered two Israeli universities to establish two university research centers. These are the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, with a research emphasis on technology and applicative sciences, and the Tel-Aviv University, with a broader interdisciplinary emphasis including political sciences and law.[61]

The underlying dual proposition continuously upheld by INCB has been that not only is academic research lagging behind the industry; but that this lag is in fact cross disciplinary, including non-technological fields and particularly social sciences and law.[62] Accordingly, in May 2014 INCB published a novel grant program with the Israeli Ministry of Science as a part of its broad and interdisciplinary appeal which approaches not only scientists and engineers, but also political scientists and lawyers.

INCB has further developed a detailed program for promoting the development of human capital. INCB initiated cyber security advanced studies programs in numerous leading technological high schools and post-graduate academic programs. One such notable endeavor focuses on high schools from the country’s socio-economically weaker regions. This project, entitled “Magshimim Leumit” (“Nationally Achieving” in Hebrew) is cooperating with the Israel’s Ministry of Education in 2013-2016 to carry out a three year program focusing on educating and developing professional skills among outstanding high school students 16 to 18 years old. The program was founded under the assumption that cyber security is yet another policy avenue for the promotion of qualitative human capital within broader distributive justice dialectics.[63]

The Bureau regularly advises the Prime Minister, the government, and its committees regarding cyberspace.[64] It is further said to consolidate the government’s administrative cyberspace aspects[65] and to advance legislation and regulation in the cyber field.[66] As of 2012, the INCB declared that the first ongoing regulatory stage would incorporate four types of regulation and accompanying objectives. These were the promotion of cyber security for organizations, the industrial and civil sectors, market regulation, and, lastly, cyber security regulation through standard setting.[67] On this front, Israel’s INCB has declared its plans to lead a process to establish recommendations for the government.[68] As of July 2012, such a process was initiated by opening regular consultations with multistakeholder experts. This process took until October 2012 and focused on the limited issue of cyber law needs.[69]

Lastly, and more pertinently, there are three archetypical strategic propositions focused on establishing a measurable regulatory framework. The first strategic proposition solicits recommendations to be made “to the Prime Minister and government regarding national cyber policy.”[70] The Israeli government and the Israeli Prime Minister’s office thus assert themselves as direct participants in a cyber security policy model initiative. The second and third thematic, albeit overly general, strategic recommendations are to “promote research and development in cyberspace and supercomputing”[71] and devise a “national concept” for coping with “emergency situations in cyberspace.”[72] These three policies are the foundation for this brief’s legal positive framework.

[26] See The State of Israel, Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Council on Research and Development and the Supreme Council on Science and Technology, eds., “National Cyber Initiative—Special Report for the Prime Minister” (2011) (Hebrew).

[27] In this backdrop the Israeli government has sought to establish a national cyber policy as soon as 2002. In the same year Israel drew a list of 19 major infrastructures incorporating power production, water supply or banking, held as either public and private with purpose of standardizing core, albeit effectively limited legal and technological protection thereof. Id., at 67. Until the establishment of the Israeli National Cyber Bureau in 2011, Israel based its rather fragmented policies on Special Resolution B/84 on “The responsibility for protecting computerized systems in the State of Israel” by the ministerial committee on national security of December 11, 2002, launched the national civilian cyberdefense policy. In balance, it has been the latter Special Resolution that catalyzed the establishment of the Israeli Cyber Bureau. See Lior Tabansky, supra note 1, at 2. Israel undertook numerous other steps to address cyber threats. In 2002 a government decision established the State Authority for Information Security (Shabak unit). The Authority is accountable for the specialized guidance of the bodies under its accountability in terms of essential computer infrastructure security against threats of terrorism and sabotage. To illustrate, when the instigation of the biometric database in Israel led to an enormous public dispute, a recent law was enacted in 2009 and consequently the State Authority for Information Security received a defensive role in prevention of cyber attacks on the biometric database.

[28] Government of Israel passed Government Resolution No. 3611, titled: Advancing National Cyberspace Capabilities, Resolution No. 3611 of the Government of August 7, 2011, http://www.pmo.gov.il/English/PrimeMinistersOffice/DivisionsAndAuthorities/cyber/Documents/Advancing%20National%20Cyberspace%20Capabilities.pdf (for the non-official English version). See generally, also the State of Israel Prime Minister’s Office—The National Cyber Bureau, http://www.pmo.gov.il/.

[29] Addendum A, section 1 (titled “Bureau Mission”) states: “The Bureau functions as an advising body for the Prime Minister, the government and its committees, which recommends national policy in the cyber field and promotes its implementation, in accordance with all law and Government Resolutions.” Id.

[30] See Jerusalem Post, Herb Keinon, Gov't to establish upgraded cyber security authority (21 September 2014).

[31] Id. Resolution No. 3611, at 1 (“To improve the defense of national infrastructures which are essential for maintaining a stable and productive life in the State of Israel and to strengthen those infrastructures, as much as possible, against cyber attack”).

[32] On the immense challenges facing a traditional law enforcement reactive cyber security deterrence, see National Research Council, Proceedings of a Workshop on Deterring Cyberattacks (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010); Martin C. Libicki, Cyberdeterrence and Cyberwar (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2009). But see, Derek E. Bambauer, “Privacy Versus Security,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology vol. 103(3) (2013) (cyber security policy must focus on mitigating breaches rather than preventing them).

[33] Resolution No. 3611, supra note 28 (“[a]dvancing Israel’s status as a center for the development of information technologies”). Thus two years after the establishment of the Israeli National Cyber Bureau, the Prime Minister, the Mayor of the southern metropolitan of city Beer-Sheva and the President of Ben Gurion University announced the establishment of a national cyber complex in Beer-Sheva, to be named CyberSpark, where INCB’s command center also presides. Two giant international companies—Lockheed Martin and IBM have said to join Deutsche Telekom and EMC in setting up their research activities in the park. See Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, “Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announces Creation of CyberSpark in Beer-Sheva” (January 27, 2014), http://in.bgu.ac.il/en/Pages/news/CyberSpark.aspx.

[34] Id. (“encouraging cooperation among academia, industry and the private sector, government ministries and special bodies”).

[35] Id. at section 1, 2.

[36] Id. at section 2, 2.

[37] Id. at Addendum B, “Regulating Responsibilities for Dealing with the Cyber Field.”

[38] Id. at section B.

[39] Id. at sections C-H.

[40] Id. at section 3, 2. Two subsidiary decisions follow. The fourth is a budgetary decision has been made in section 4, stating: “The budget to implement this Resolution will be determined by the Prime Minister in consultation with the Minister of Finance, and will be submitted to the government for approval.” The fifth decision upheld in section 5, at 2, excludes archetypical “Special bodies” from the mandate of the Bureau. Section D in the Definition part defines these as follows: “Special Bodies”—the Israel Defense Forces, the Israeli Police, Israel Security Agency (“Shabak”), the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations (“Mossad”) and the defense establishment by means of the Head of Security of the Defense Establishment (DSDE).”

[41] Id. at Recommendation 14.

[42] Id. at Recommendation 12. Recommendation 14 similarly calls for the “formulation of and the wise use of cyberspace.”

[43] The Security & Defense Agenda (SDA) report, supra note 23, at 71.

[44] Id. at 83.

[45] Id. at 64.

[46] Id. at 80.

[47] Id. at 61.

[48] Id. at Recommendation 9. In particular, Recommendations 10 and 11 offers to assemble intelligence picture from all intelligence bodies and similarly reiterate a “national situation status” concerning cyber security, respectively.

[49] Id. at Recommendation 15. Substantive international cooperation is still deemed questionable by INCB, as discussed infra, Part C.2. See also Interview with Mr. Tal Goldstein from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau, supra note 3.

[50] Id. at Recommendation 5.

[51] Id. at Recommendation 13.

[52] Id. at Recommendation 13.

[53] Id.

[54] Id.

[55] Id. at Recommendation 16.

[56] See Haaretz, Anshel Pfeffer and Gili Cohen, Who protects the Israeli civilian home front from cyber attack? (5.2.2013).

[57] Id.

[58] Israel National Cyber Bureau publications, the Inauguration of the KIDMA—Promotion of R&D in Cyber Security program (November 12, 2013) (in Hebrew), http://www.pmo.gov.il/MediaCenter/Spokesman/Pages/spokeKidma131112.aspx. See also Israel’s Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS), Newsletter 02-2012 (21 Nov. 2012) (in Hebrew), http://www.moital.gov.il/NR/rdonlyres/89646959-5455-4A5A-99FD-C4B07D07E8E5/0/syber122012_3.pdf. The program includes upgraded funding for cyber security startups operating in technological incubators, a higher finance percentile in related venture capital funds, a fastened application examination process, etc.

[59] Id.

[60] Israel National Cyber Bureau publications, Announcement concerning the establishment of the joint The Israeli Ministry of Defense’s Research Authority, Development of Ammunition and Technological Infrastructure (MAFAT)-INCB MASAD project, http://www.pmo.gov.il/MediaCenter/Spokesman/Pages/spokemasad311012.aspx (in Hebrew).

[61] See, e.g., Major Cyber Security Center Launched at Tel Aviv University (16 September 2014), http://english.tau.ac.il/blavatnik_cyber_center. Two additional university research centers are presently being discussed. See Interview with Mr. Tal Goldstein from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau, supra note 3.

[62] Id.

[63] The Israeli Prime Minister’s Office, “Announcement about the inauguration of the ‘Magshimim Leumit’ project,” December 21, 2012, http://www.pmo.gov.il/MediaCenter/Events/Pages/eventmagshimim311212.aspx (in Hebrew).

[64] Id. at Recommendation 1. Notwithstanding the Bureau’s overarching mandate, in matters of foreign affairs and security, the advice provided to the government, to its committees and to the ministers, will be provided on behalf of the Bureau by means of the Israeli National Security Council. Recommendation 19 offers that the Bureau carry out any other role in the cyber field determined by the Prime Minister.

[65] Id. at Recommendation 2. The Bureau will also offer supporting cross agency coordination thereof. Recommendation 4 further adds that the Bureau will “inform all the relevant bodies, as needed, about the complementary cyberspace-related policy guidelines.”

[66] Id. at Recommendation 17. Recommendation 18 adds that the Bureau will serve as a regulating body regulating body in fields related to cyber security.

[67] See INCB’s Public Consultation with multi stakeholders in preparing cyber security regulation (in Hebrew), http://www.pmo.gov.il/sitecollectiondocuments/pmo/cyber.doc.

[68] Id.

[69] Id. It included four stages. at a start, INCB collected and processed expert testimonies. Soon after a public advisory committee was established. Then a series of open consultations as well as particular consultations took place. Lastly, INCB generated a list of recommendation which were at first open for public commentary soon to pass as INCB final regulation recommendation for the Israeli government consideration. See also interview with Mr. Amit Ashkenazi from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau (18 September 2014) (on file with author) (adding that it is clear that adapted legislation is needed yet the intention is not to opt for an overarching statute but modular and proportional set of statutory frameworks for separate cyber threats).

[70] Id. at Addendum A, section 2 (titled “Bureau Goals”), Recommendation 3 (“[t]o guide the relevant bodies regarding the policies decided upon by the government and/or the Prime Minister; to implement the policy and follow-up on the implementation.”).

[71] Id. at Recommendation 6. Such emblematic “research and development” should be promoted by what remain undefined “professional bodies.”

[72] Id. at Recommendation 8. There remains yet a fourth trade policy-related recommendation that albeit seminal in the Israeli Cyber Bureau’s mandate, is nevertheless limited to advancement of the local economy. Recommendation 7 thus flatly calls upon the Bureau to “work to encourage the cyber industry in Israel,” Recommendation 7. This important yet only loosely irrelevant to cyber security policy, will remain outside the scope this policy brief.

III. The Positive Framework

This section maps the cyber security themes that constitute national cyber security policies worldwide. It introduces and discusses these fields of law with the goal of identifying the main legal concerns any national cyber security policy might address. First, it discusses cyber security definitions, including the range of cyber threats, types of cyber security risks, and types of practices not designated as cyber security risks. Second, models of cooperation over cyber security are reviewed, including inter-governmental, public-private platform (PPP), and regional cooperation. Lastly, the brief considers specific fields of law for examination, including cyber security and international law, cyber attacks and international humanitarian law, cyber treaties and international treaty law, national responsibility for cyber attacks and state responsibility, cyber crimes and cyber security, cyber attacks and international human rights law, privacy and cyber security, cyber security and telecommunications law, and cyber security and contractual obligations.

A. Cyber Security Definitions

A cyber security policy model should adhere to three categories of definitions, as these are repeatedly present in such leading policies. Defining the range of cyber threats, ranging from deliberate attacks for military or political advantage, through the forms of cyber crime and cyber warfare, and cyber terror against civil and military objects. Defining types of cyber security risks, ranging from concealment (Trojan horse), infectious malware and malware for profit (vector, control, maintenance, and payload), Botnets, cybercrime business models (advertising, theft, support), and chokepoints (anti-malware, registrars, payments, site takedown, and blacklisting). Defining types of practices not designated as cyber security risks*, including joke software, hoaxes, scams, spam, and cookies.

B. Models of Cooperation Over Cyber Security

A cyber security policy model ought to map the possibilities and limitations regarding the creation of cooperative international arrangements, involving governments and civil society to reduce risks to cyber security. INCB to date still witnesses only a limited degree of international cooperation. Two pivotal reasons account for this. First, few countries practice cyber security policies. A small number of countries actually have standing traditions of cyber industries supported by policy-making mechanisms and cyber security administrative organs. Second, it is questionable to what extent international consensus could be achieved, against the backdrop of regional and even narrower bilateral alternatives.[73] Notwithstanding these regulatory constraints, numerous avenues for cooperation exist across countries.

[73] See Interview with Mr. Tal Goldstein from the Israeli National Cyber Bureau, supra note 3.

1. Inter-Governmental Cooperation

a. The European Union

The EU Cyber Security Strategy “Protection of an open and free Internet and opportunities in the digital world” (February 2013) and associated draft directives guide the EU’s approach to cyber security. The Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning measures to ensure a high common level of network and information security across the Union (February 2013) set the framework at the European Union for cyber security. The 2013 EU Cyber Security Strategy is being gradually implemented by EU member states with the purpose of minimizing policy fragmentation among member states. The EU’s policy resonates within the 2009 EU Commission’s issuance of a communication on Critical Information Infrastructure Protection (CIIP), titled “Protecting Europe from large scale cyber-attacks and disruptions: enhancing preparedness, security and resilience.”[74] Similar to the Israeli case, the EU Commission recently noted that the upcoming challenges for Europe are—broadly—fourfold. First, there are uneven and uncoordinated national approaches by EU member states. Second, there is a need for a new European governance model for critical information infrastructures. Third, there is limited European early warning and incident response capability. Last, there is the need for appropriate international cooperation. Collaboration with non-European national cyber security policies, such as the Israeli policies, would satisfy the European Commission’s call to engage the global community to develop a set of principles reflecting European core values for the net’s resilience.

Moreover, a cyber security policy model could reflect cooperation to the extent of the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection set forth in Directive EU COM(2006) 786. This program obliges all member states to the European Economic Area (EEA) to adopt the components of the Program into their national statutes.[75] In the Israeli case, Israel and the EU are continually discussing EEA’s integration based on a direct association agreement with Israel so a harmonized cyber security policy brief may be issued in a timely manner.

Lastly, the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA) operates for EU institutions and member states. ENISA serves as the EU’s coordinated response to cyber security issues of the European Union and offers yet another platform for inter-governmental cooperation over cyber security in the EU.[76]

[74] See EU Commission, Protecting Europe from large-scale cyber-attacks and disruptions: enhancing preparedness, security and resilience (2009), http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/policy/nis/docs/comm_ciip/comm_en.pdf.

[75] European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection set forth in a Directive EU COM(2006) 786, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/com/2006/com2006_0786en01.pdf.

[76] For ENISA’s policy, see European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA), “National Cyber Security Strategies: Practical Guide on Development and Execution,” (December 2012).

b. The United States

A cyber security policy model could further borrow from the case of the 2009 Comprehensive National Cyber-security Initiative (CNCI) put forward by the United States government and the subsequent 2011 International Strategy for Cyberspace (White House, May 2011).[77] The details of this policy will be discussed in Part C.

Equally, most elements of the United States’ policy focus on the federal government’s cyber security, instead of cyber security on the state level. In balance, however, relative to the Israeli case, the United States has still not firmly decided what the regulatory apparatus of the federal government should be regarding the protection of critical infrastructure owned and operated by the private sector. Be that as it may, the United States’ designated policy priorities include (1) economics, (2) protecting its networks, (3) law enforcement, (4) military, (5) Internet governance, (6) international development, and (7) Internet freedom, as will be discussed in Part C.

[77] The White House, President Barack Obama, “The Comprehensive National Cybersecurity Initiative,” http://www.whitehouse.gov/cybersecurity/comprehensive-national-cybersecurity-initiative.

2. Regional Cooperation

One example of a regional or inter-regional cyber security initiative is the Asia-Pacific’s regional cooperation over cyber security in the National Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) by APCERT. This initiative facilitates regional cooperation and coordination amongst CERTs and Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs).[78]

Another regional initiative is the comparable Organization of American States’ (OAS) portal aimed at augmenting cyber security and regional responses to cybercrime.[79] This rather early-stage portal was created primarily to facilitate and streamline cooperation and information exchange among government experts from OAS member states.

[78] Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP), Memorandum No. 20, Ensuring A Safer Cyber Security Environment (May 2012).

[79] See Inter-American Cooperation Portal on Cyber-Crime, http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/cyber.htm.

3. Public-Private Platform (PPP)

The business sector has taken on technological standardization initiatives since the early days of cyber security. Technological standardization has been advanced to increase the security of products, services, and networks. One such important initiative came from the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Its successful effort to promote development and adoption of security extensions for the domain name system (DNS) illustrates how a private sector-led initiative backed by government participation can significantly enhance the Internet’s security.[80]

Another important example for governmental cooperation with commercial enterprises and educational institutions, albeit with a technical orientation, are Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs). They are intended to promote information sharing and coordination among government agencies and the private sector against cyber-attacks, and identify and correct cyber-vulnerabilities.[81] The lessons from CERTs are still rather preliminary and necessitate further technical testing.

[80] See European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA), “Good Practices Guide for Deploying DNSSEC,” http://www.enisa.europa.eu/act/res/technologies/tech/gpgdnssec.

[81] See the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams, http://www.first.org. The European Government CERTs (EGC) Group (http://www.egc-group.org) has 11 member organizations.

4. Economics of Information Security Considerations

Evaluation of how different stakeholders’ incentives align should include efficiency considerations.[82] Thus, cyber security policy may offer not only direct regulation, but also indirect regulation aimed at incentivizing efficient behavior by end-users. To name but a few suggestions, these range from optimal security enhancing incentives, such as tax subsidies for compatible standards, to incentivizing whistle blowing against hazardous Internet users or even corporate espionage.

[82] Tyler Moore, Introducing the Economics of Cybersecurity: Principles and Policy Options, National Research Council, Proceedings of a Workshop (2010).

5. Administrative Responses to Cyber Crises

These offer additional possibilities regarding the creation of a cyber security policy model. This is the motivation for the Israeli Bureau’s call to define emergency cyber situations in Recommendation 8 to the INCB’s recommendations, and the Bureau’s call for definition for cyber warnings in Recommendation 13 to the INCB’s recommendations. This issue is discussed in Part C.

6. Linking International Cyber Security Policy to Domestic Law

Attention should be given to information asymmetries and principle-agent constraints when applying international cyber security regulation to the national sphere.[83] Such legal adaptations generally support the need to preserve separate national discretion, realistic and even lenient regulatory timetables, administrative safe harbors, and even restrained judicial discretion, while still evaluating local differentiated security risks and challenges.

[83] Daniel Jacob Hemel, Regulatory Consolidation and Cross-Border Coordination: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom, Yale Journal on Regulation vol. 28(1) (2011) (offering a regulatory paradox whereby in areas where a single regulatory agency enjoys consolidated control over a particular policy matter at the domestic level, that agency is less willing to restrict its policy-making discretion through an international agreement and vice-versa).

IV. A Cross-Section Comparison

Over thirty countries have thus far declared archetypical national cyber security strategies.[84] With quite a bit of similarity, countries have conducted active debates on codes of conduct for cyberspace, application of international laws, Internet governance and other aspects of functions, roles, and circumstances of cyberspace. National policies thus deal with the risks surrounding cyberspace from such viewpoints as national security and economic growth. Such national state practice has ultimately turned the functions, roles, and circumstances of cyberspace into a common international issue. Designing a cyber security policy model should therefore be especially attuned to leading national cyber security policies. This part offers a cross-sectional comparison between five such countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and the Netherlands.

[84] See, e.g., European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA), National Cyber Security Strategies in the World, http://www.enisa.europa.eu/activities/Resilience-and-CIIP/national-cyber-security-strategies-ncsss/national-cyber-security-strategies-in-the-world (last retrieved 14 July 2014).

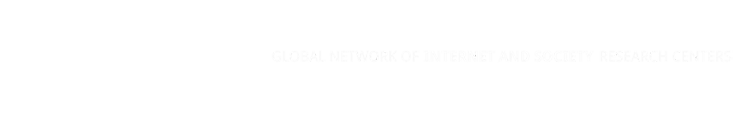

United States

[85] Id.

[86] Id.

[87] Id. at 18.

[88] Id. at 19.

[89] Id. at 20.

[90] Id. at 22.

[91] Id. at 21.

[92] Id. at 23.

[93] Id. at 24.

[94] Id.

[95] Id. at 17.

[96] Id. at 18.

[97] Id. at 20.

[98] Id. at 17.

[99] Id. at 18.

[100] Id. at 19.

[101] Id.

[102] Id.

[103] Id. at 22.

[104] Id.

[105] Id.

[106] Id.

[107] Id. at 23.

[108] Id. at 15.

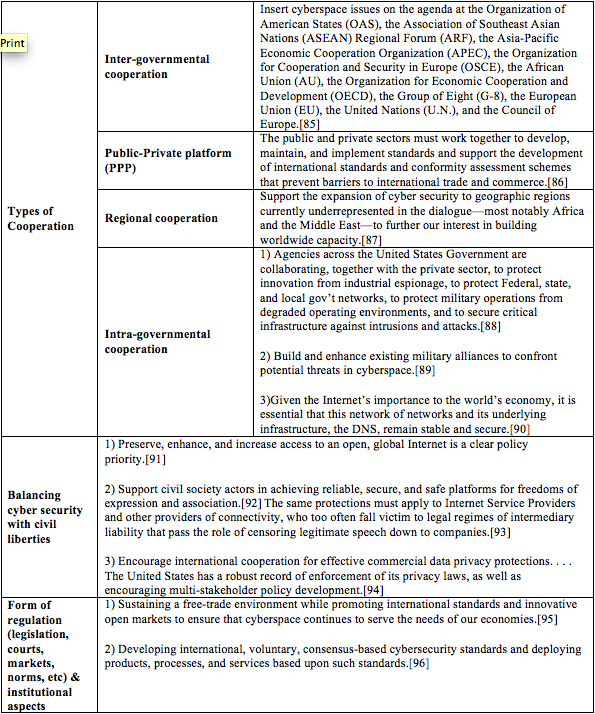

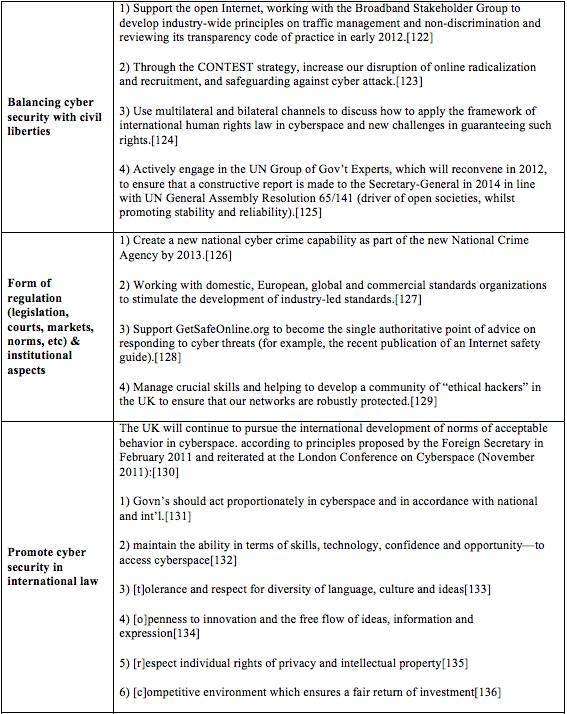

United Kingdom (2009)[109]

[109] The UK Cyber Security Strategy, Protecting and promoting the UK in a digital world (November 2011). Earlier, Great Britain published its 2009 policy initiative to promote growth via the Internet. See UK Cabinet Office, “Cyber Security Strategy of the United Kingdom: Safety, security and resilience in cyber space” (London: The Cabinet Office, CM 7642, June 2009), http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm76/7642/7642.pdf.

[110] Id. at 22.

[111] Id. at 39.

[112] Id.

[113] Id. at 22.

[114] Id.

[115] Id. at 39.

[116] Id. at 41.

[117] Id.

[118] Id. at 41.

[119] Id. at 40.

[120] Id. at 39.

[121] Id.

[122] Id. at 39.

[123] Id.

[124] Id. at 40.

[125] Id. at 41.

[126] Id. at 36.

[127] Id. at 37.

[128] Id. at 38.

[129] Id. at 42.

[130] Id. at 22.

[131] Id.

[132] Id.

[133] Id.

[134] Id.

[135] Id.

[136] Id.

[137] Id. at 36.

[138] Id.

[139] Id.

[140] Id.

[141] Id. at 22.

[142] Id. at 42.

[143] Id.

[144] Id. at 38.

[145] Id. at 42.

[146] The UK Cyber Security Strategy. Id. at 38.

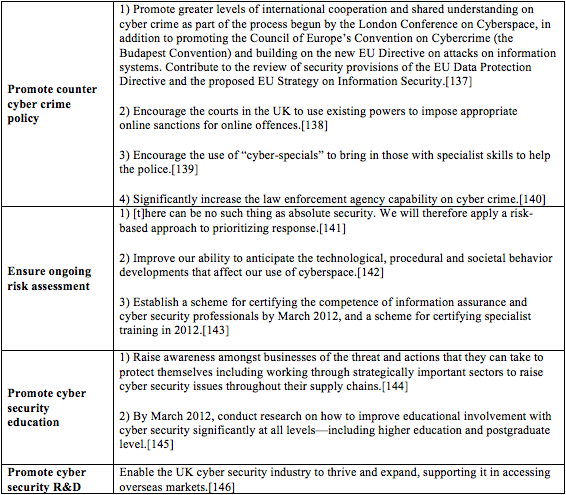

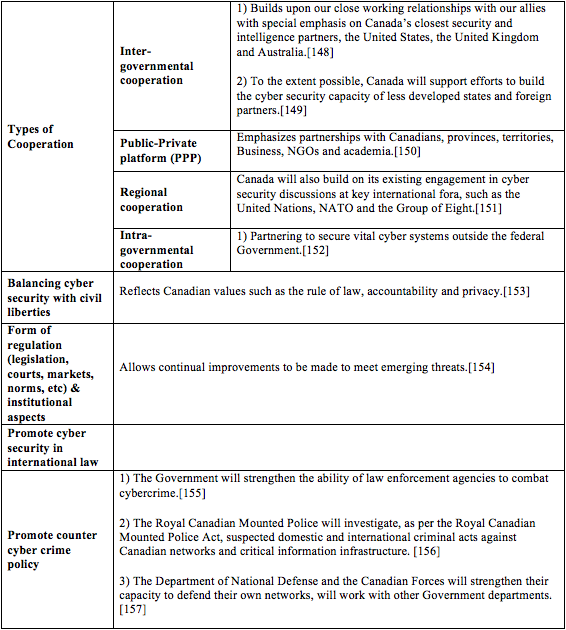

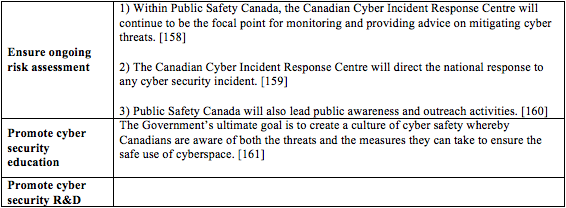

Canada[147]

[147] See Government of Canada, Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy for a Stronger and More Prosperous Canada, (2010), http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/cbr-scrt-strtgy/cbr-scrt-strtgy-eng.pdf.

[148] Id. at 8 (“Three of our closest security and intelligence partners, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, recently released their own plans to secure cyberspace. Many of the guiding principles and operational priorities set out in those reports resemble our own.”).

[149] Id. at 9.

[150] Id. at 9 (“Responsibility for digital security in the Netherlands lies with many parties. There is still insufficient cohesion between policy initiatives, public information, and operational cooperation. The Government therefore considers it essential to foster a collaborative approach between the public sector, the private sector, and knowledge institutions.”).

[151] Id. (Canada is “one of the non-European states that have signed the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime”).

[152] Id.

[153] Id.

[154] Id. at 8.

[155] Id. at 9.

[156] Id. (“The Canadian Security Intelligence Service will analyze and investigate domestic and international threats to the security of Canada.”), at 10.

[157] Id. at 10.

[158] Id. at 10.

[159] Id.

[160] Id.

[161] Id. at 13.

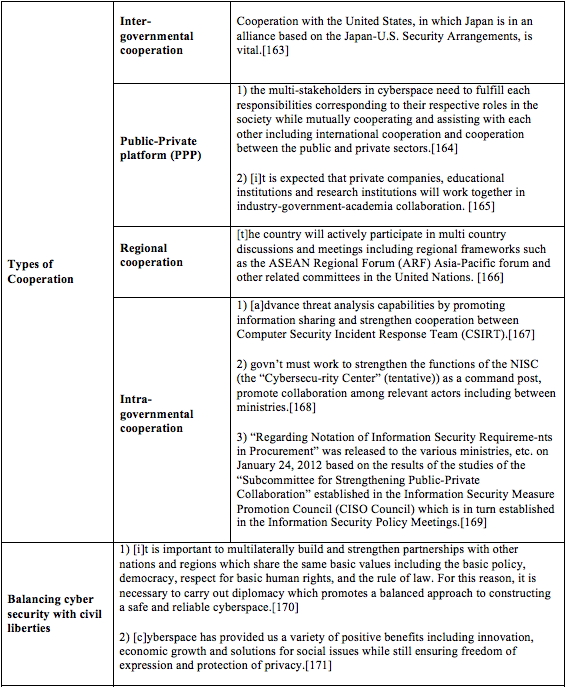

Japan[162]

[162] See Japanese Information Security Policy Council, Information Security Strategy for protecting the nation (2013). Earlier the Japanese Information Security Policy Council released the Information Security Strategy for Protecting the Nation, (May 11, 2010), at: http://www.nisc.go.jp/eng/pdf/New_Strategy_English.pdf.

[163] Id. at 50.

[164] Id. at 22.

[165] Id. at 26.

[166] Id. at 50.

[167] Id. at 22 (CSIRT is a “system at businesses and government organizations for monitoring to check if any security issues exist with information systems and for carrying out investigations including cause analysis and extent of impact in the event an incident occurs”).

[168] Id. at 24.

[169] Id. at 32.

[170] Id. at 49.

[171] Id. at 20.

[172] Id. at 22.

[173] Id.

[174] Id. at 20.

[175] Id. at 23.

[176] Id. at 28.

[177] Id. at 49-50.

[178] Id. at 40.

[179] Id. at 40 (NCFTA is “a non-profit organization established in the United States and made up of members from the FBI, private sector businesses and academic institutions.”).

[180] Id. at 52. The Convention on Cybercrime has been ratified in the Japanese Diet in April of 2004, coming into effect on November 1, 2012 through the enactment of the “Law for Partial Revision of the Penal Code, etc. to Respond to Increase in International and Organized Crimes and Advancement of Information Processing.”

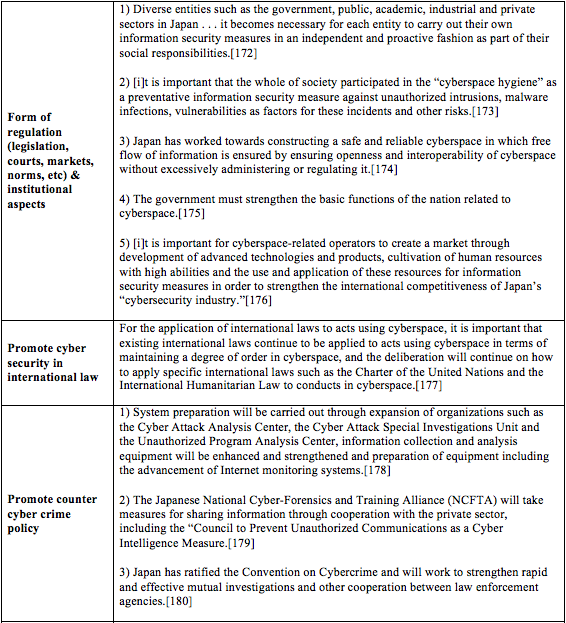

[181] Id. at 32.

[182] Japanese Information Security Policy Council, Information Security Strategy for protecting the nation (2013), at 33. Cyber incident Mobile Assistant Team (Information security emergency support team) (CYMAT) was established in in June of 2012, and provides technical support and advice related to preventing spread of damages, recovery, cause investigation and recurrence prevention in the event of cyber-attacks. ministries or other agencies under the National Information Security Center director who is the government CISO.

[183] Japanese Information Security Policy Council, Information Security Strategy for protecting the nation (2013), at 34.

[184] Id. at 27.

[185] Id. at 48.

[186] Japanese Information Security Policy Council, Information Security Strategy for protecting the nation (2013), at 45.

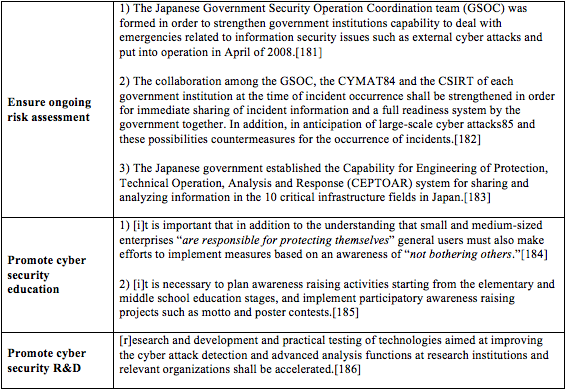

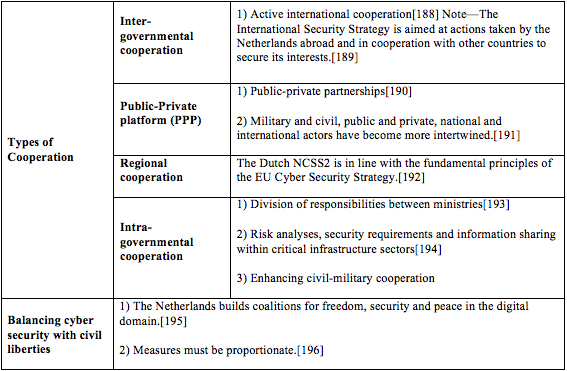

The Netherlands[187]

[187] See National Cyber Security, “Strategy 2: From awareness to capability” (2013); see also Ministry of Science and Justice, The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), “The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands” (2011).

[188] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011). See id. at 6 (“The Netherlands supports and actively contributes to efforts such as the EU’s Digital Agenda for Europe and Internal Security Strategy, NATO’s development of cyber defense policy as part of its new strategic vision, the Internet Governance Forum, and other partnerships.”).

[189] Id. at 9.

[190] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), “The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands” (2011), at 5 (“Every party concerned must gain value from participation in joint initiatives—an outcome that will be facilitated by an effective cooperation model with clearly defined tasks, responsibilities, powers, and guarantees.”).

[191] See National Cyber Security, Strategy 2: From awareness to capability (2013); id. at 14.

[192] Id. at 9.

[193] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011), Id. at 6 (“The Minister of Security and Justice is, in accordance with the National Security Strategy, responsible for coherence and cooperation on cyber security. At the same time, each party in the cyber security system has its own tasks and responsibilities.”).

[194] See National Cyber Security, Strategy 2: From awareness to capability (2013); id. at 9 (“the government, working with vital parties, identifies critical ICT-dependent systems, services and processes.”).

[195] Id. at 9.

[196] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011), Id. at 6 (“[i]t aims to protect our society’s core values, such as privacy, respect for others, and fundamental rights such as freedom of expression and information gathering. We still need a balance between our desire for public and national security and for protection of our fundamental rights.”).

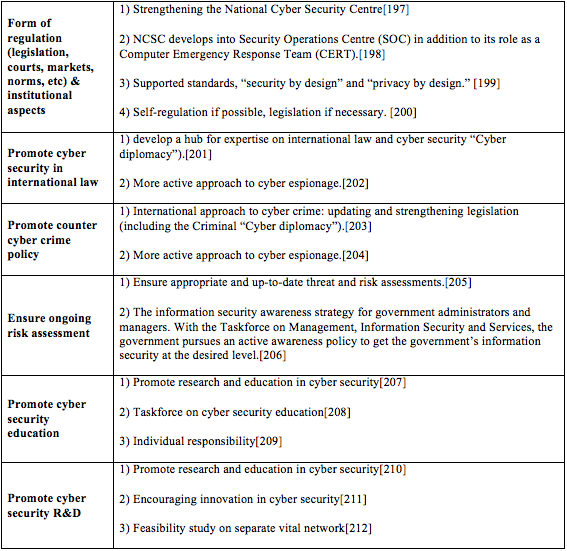

[197] Id. at 10 (“the NCSC assumes the role of expert authority, providing advice to private and public parties involved, both when asked and at its own initiative.”).

[198] Id. (“Finally, based on its own detection capability and its triage role in crises, the NCSC develops into Security Operations Centre (SOC) in addition to its role as a Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT).”).

[199] Id. (“Together with private sector partners, the government works to develop standards that can be used to protect and improve the security of ICT products and services.”).

[200] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011), Id. at 6 (“The public and private sectors will achieve the ICT security they seek primarily through self-regulation. If self-regulation does not work, the Government will examine the scope for legislation.”).

[201] Id. (“The goal of the hub for expertise is to promote the peaceful use of the digital domain. To this end, the Netherlands combines knowledge from existing centers. The centre brings together international experts and policymakers, diplomats, military personnel and NGOs.”).

[202] Id. at 9 (“To this end, the intelligence and security services have combined their cyber capabilities in the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU)”). Both 2010 (cyber conflict) and 2012 (cyber espionage) cyber security scenarios were included in the NV Strategy. Id. at 14.

[203] Id. (“The goal of the hub for expertise is to promote the peaceful use of the digital domain. To this end, the Netherlands combines knowledge from existing centers. The centre brings together international experts and policymakers, diplomats, military personnel and NGOs.”).

[204] Id. at 9 (“To this end, the intelligence and security services have combined their cyber capabilities in the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU)”). Both 2010 (cyber conflict) and 2012 (cyber espionage) cyber security scenarios were included in the NV Strategy. Id. at 14.

[205] See National Cyber Security, Strategy 2: From awareness to capability (2013); id. at 8.

[206] Id. at 14 (“This is not only an important precondition for the implementation of the government’s plans concerning the concept of the digital government 2017, but also in view of the Government-Wide Implementation Agenda for eGovernment Services until 2015 (i-NUP), in which a basic infrastructure will be realized.”).

[207] Id. at 8.

[208] Id. (“To enlarge the pool of cyber security experts and enhance users’ proficiency with cyber security, the business community and the government join forces to improve the quality and breadth of ICT education at all academic levels (primary, secondary and professional education)”).

[209] The National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS), The Ministry of Security and Justice, the Netherlands (2011), Id. at 6 (“All users (individuals, businesses, institutions, and public bodies) should take appropriate measures to secure their own ICT systems and networks and to avoid security risks to others”.).

[210] Id. at 8.

[211] Id. National Cyber Security, Strategy 2: From awareness to capability (2013) (“coordination of supply and demand, which can be achieved by linking innovation initiatives to leading sector policy. In addition, the government, the business community and the world of academia will launch a cyber security innovation platform where start-ups, established companies, students and researchers can connect, inspire one another and attune research supply and demand.”).

[212] Id. at 9 (“An exploratory study is conducted to determine whether it is possible and useful, from both a technical and organizational perspective, to create a separate ICT network for public and private vital processes.”).*

V. Best Practices and Conclusion

Israel’s establishment of the INCB cyber command and its upward national cyber policy have five facets. These are: 1) the implementation of a medium-run five-year plan to scale up the country as a world leader in cyber security; 2) the inclusion of investment in research and development (R&D) based on interdisciplinary university research centers and backed by extensive governmental funding; 3) encouraging industry to develop new technologies; 4) the setting up of a super computer center; and 5) boosting academic studies in cybernetics.

The effectiveness of Israel’s cyber policy is still unfolding, and several caveats also labeled as best practices for future national cyber security policy models apply. First, cyber security is still an evolving discipline where future cyber risks and threats are largely unknown. Any cyber security policy model should thus reflect this and include regulatory modularity and administrative flexibility. Furthermore, national cyber security policies often carry a reactive nature as they regularly emerge after equivalent cyber threats evolve, and Israel’s experience is no different. As a result, taken from the organizational angle, cyber security policies do not replace administrative organizations because these organizations end up coordinating the policies. Israel’s INCB serves as proof of this situation. INCB’s rather modest thirty-employee core scarcely has the means to battle cyber threats directly. Instead, INCB coordinates the cyber battles of myriad local defenses and civil agencies and corporations. A third caveat calling for certain restraint applies in the Israeli example. Accordingly, different than in most cyber-literate countries worldwide, Israel’s INCB materialized in reaction to momentous national security threats unfamiliar or at least moderately undemanding in relation to most of its counterparts. The fact that the cyber attacks that Israel faced were national security threats, as opposed to the less dangerous cyber crime that many other nations face, led to a different kind of regulatory regime.

That said, this comparison of policies yields some observations on commonalities between the policies of the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands and Israel:

Promoting cyber security R&D: In the experiences of the United States, Israel, and the United Kingdom, national commitment to research and development in cyber security was essential for two main reasons. Firstly, it cultivates dynamic international research communities able to take on next-generation challenges to cyber security. Secondly, it enables national cyber security industries to expand while supporting them in accessing overseas markets. In each country, such practices are adapted to the specific scientific educational frameworks and underlying national preferences.

Promote cyber security education: There seem to be three types of educational policies within the cyber security context. The first are educational programs that help nations gain the resources and skills to build core capacities in technology and cyber security. The promotion of cyber security education is meant to raise awareness among businesses of this threat and of the protective actions they may take. In recent years, the United States most noticeably helped make education around cyber security a priority at multilateral forums such as the OAS, APEC, and the UN. Cyber security-related education and training has another purpose within the related context of cyber crime. In this context cyber security, educational, and training programs are aimed at law enforcement officials, forensic specialists, jurists, and legislators. The third type of educational policy is intended to improve educational involvement at the higher education and postgraduate level, and construct a vibrant research community and related cyber security industries.

Ensuring ongoing risk assessment: All national cyber security policies reviewed have developed a detailed watch, warning, and incident response to cyber threats through exchanging information within trusted networks. Similarly, national policies systematically participate in national and international cyber security exercises to elevate and strengthen established security procedures. Lastly, national policies have established equivalent schemes for certifying the competence of information assurance and cyber security.

Promote counter cyber crime policy: Cyber crime policy has developed both multilaterally, such as through the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cyber Crime (the Budapest Convention), and bilaterally. Given cyber crime’s international character, it is important to encourage other countries to become parties to the Convention and help current non-parties use the Convention as a basis for their own laws. Within the European context, cyber crime policy further builds upon the new EU Directive on attacks on information systems. Equally, all reviewed countries have committed to increase their law enforcement capabilities to combat cybercrime. In balance, however, a cyber security policy model should carefully scale institutional preferences related to online law enforcement at large. Canada, to name one example, has delegated to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police domestic and international enforcement responsibilities. Yet the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, by the same token, is mandated to analyze and investigate domestic and international threats to the security of Canada.

Promote cyber security in international law: All countries reviewed share a unified commitment to the rule of law in cyberspace and to international law. The United Kingdom noticeably has explicitly adopted an additional international norms-based policy of tolerance and respect for diversity of language, culture, and ideas. The Netherlands added a commitment to upholding peace in cyber security enforcement. Among the individual rights mentioned are rights of privacy, freedom of speech, and intellectual property. National policies reviewed have not mentioned international humanitarian law or state responsibility policy preferences. For the application of international laws to cyberspace, it is important that existing international laws be adapted, although key binding treaties and international laws (and even mere state practice) are still missing.

Form of regulation (legislation, courts, markets, norms, etc) & institutional aspects: The United States unlike other reviewed countries has elaborated the role of technological standards in regulating cyber security. It has consequently called for industry-government cooperation over an open, voluntary, and compatible standardization of the Internet’s security. The US government further reiterates its understanding that such standard setting is not only commercially beneficial to the US economy, but should also be industry-led. There is thus a conceptual gap between the United States and Canada, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands over this issue. The latter countries implicitly undermine the role of standards in regulating the Internet’s security as they opt for either self-regulation, such as in the Netherlands, or state regulation backed by judicial review, in the case of the United Kingdom or Canada.

Balancing cyber security with civil liberties: National cyber security policies share a commitment to enhancing access to a secure, private, reliable, and safe Internet. The United States further offers to protect Internet service providers (ISPs) and other types of providers. The US national policy provides such protection while explaining that ISPs too often fall victim to legal regimes that pass off the role of censoring legitimate speech to such companies. Balancing cyber security with civil liberties is further promoted by international and regional partnerships with countries that share comparable basic values. Such values mentioned were commonly associated with freedom of speech and association, privacy, respect for basic human rights, and the rule of law.

Type of cooperation: Cyber security policies seem to be deeply intertwined with cooperation between countries internationally and regionally. Leading regional cooperative frameworks are NATO’s cyber defense policy, ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) Asia-Pacific forum, the Council of Europe, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Governments similarly collaborate with the private sector in public-private platform (PPP) initiatives in order to protect federal, state, and local governments, as cyber threats are said to be business-driven in part. The United States’ cyber security policy further calls for enhancing civil-military cooperation.

In international cooperation, national cyber security policies deem cyber threats to be strongly associated with countries that share similar socio-political values and interests. The countries reviewed were Western democratic countries, or otherwise close security and intelligence partners. Examples include Canada’s close intelligence partnerships with the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, and Japan’s strategic alliance with the United States.