Intermediary Liability in the United States

This paper describes and assesses the intermediary liability landscape in the United States, providing an overview of major US legal regimes that protect online intermediaries from liability for user content. It then offers a series of case studies describing ways in which US-based companies and other organizations have structured their operations in compliance with and in response to US law.

Intermediary Liability in the United States

Authors: Adam Holland, Chris Bavitz, Jeff Hermes, Andy Sellars, Ryan Budish, Michael Lambert, and Nick Decoster

Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University

Abstract: This paper describes and assesses the intermediary liability landscape in the United States. It provides an overview of major US legal regimes that protect online intermediaries in cases where third-parties seek to hold them liable for the conduct of their users, addressing both the Digital Millennium Copyright Act safe harbor enshrined in Section 512 of the United States Copyright Act and Section 230(c) of the Communications Decency Act. It then offers a series of case studies describing ways in which US-based companies and other organizations have structured their operations in compliance with and in response to US law. The paper describes Craiglist’s response to efforts to hold it responsible for sex trafficking that occurred on the site; the ContentID copyright and VERO trademark programs implemented by YouTube and eBay, respectively; and the reactions of intermediaries to allegations of wrongdoing by Wikileaks. It provides an assessment of the importance of transparency reporting for online intermediaries as they seek to address tensions between requirements of legal compliance and the need to secure users’ trust. And, it concludes with a detailed and thematically-organized literature review that summarizes the state of scholarship in this space.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Legal Landscape Primer

A. General Content Liability

1. Traditional Defamation Liability for Intermediaries

2. Traditional Privacy Liability for Intermediaries

3. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

B. Copyright

1. A General Overview of Secondary Liability for Copyright Infringement

2. The DMCA’s Safe Harbor

C. Other Intellectual Property Laws

1. Trademark

2. Misappropriation and Right of Publicity Laws

3. The Espionage Act

4. Surveillance Law

III. Case Studies

A. Sex Trafficking in Online Classified Advertising – Craigslist.org and Backpage.com

1. Introduction

2. “Erotic” and “Adult” Advertisements on Craigslist – Negotiation Leads to Concession

3. “Adult Content” on Backpage.com – State Legislation and Defiance

4. Attention Turns to Section 230 Itself – The Current Legislative Debate

5. Conclusion

B. Private Ordering to Respond to Copyright Concerns: YouTube’s ContentID Program

1. YouTube Is Created

2. What Is Content ID?

3. What Can An Examination Of YouTube And ContentID Tell Us About Online Intermediaries And Private Ordering?

4. What Has Content ID Made Possible?

5. Negative Outcomes

6. Conclusion

C. Private Ordering to Respond to Trademark Concerns – eBay’s VERO Program

1. Tiffany v. eBay

2. Moving Forward

3. The VeRO Program

4. History of VeRO

5. Outcomes

D. The State as Soft Power – The Intermediaries Around Wikileaks

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Legal Liability

4. Online Intermediaries React

5. Analysis

E. Online Intermediaries and Transparency Reporting

1. Introduction

2. Legal Background

3. Transparency Reporting: Resolving the Tension Between Compliance and Trust?

4. National Security Data is Complicated

5. Transparency Reports Describe a Passive Event

6. Companies Are Competing With Transparency Reports

7. Conclusion

F. Appendix A: Literature Review

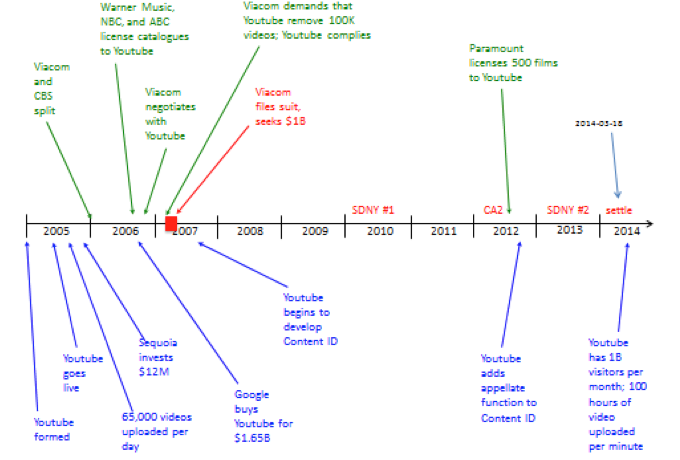

G. Appendix B: Youtube and ContentID Timeline

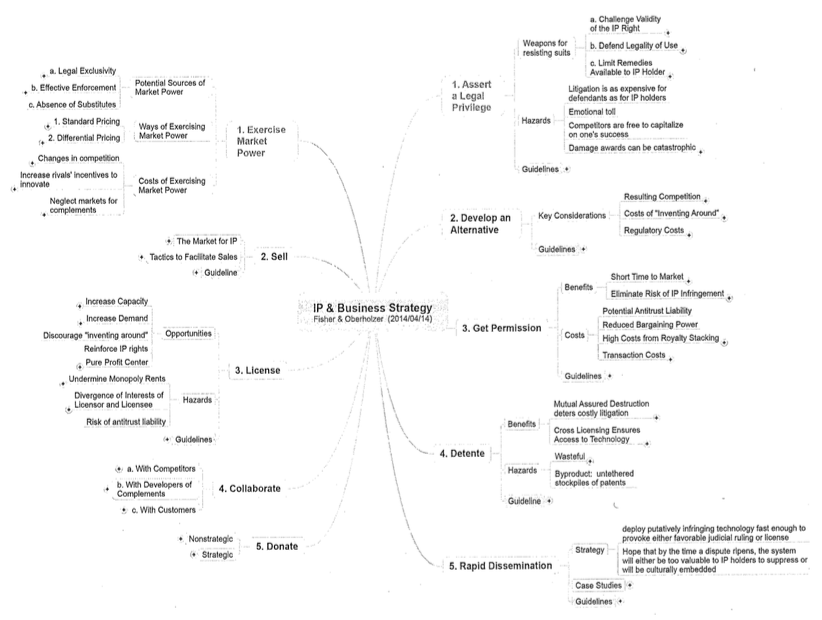

H. Appendix C: Business Strategies Mind-Map

I. Introduction

The United States offers a unique and interesting case, from both a legal and policy perspective, for study of the governance landscape for online intermediaries. This is true for at least two major reasons.

First, the US is the birthplace of, and home to, many major global Internet platforms that host content and make this content available to users. It is thus unsurprising that US law incorporates significant protections for such online intermediaries in cases where third parties seek to hold them liable for the conduct of their users. At the same time, the US is also home to a significant and robust content industry that has played a major role in shaping its intellectual property – particularly copyright – regimes. The tension between content owners (who place a premium on preventing infringement of the content that drives their traditional business models) and intermediaries (which require immunity from third-party claims in order to avoid crippling financial liability) raises fundamental questions about the role of government and the prioritization of business interests.

Second, US law provides robust protections for speech, rooted in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Government-sanctioned restraints on speech – particularly prior restraints imposed without significant consideration to due process – are very strongly disfavored under US law. A court order requiring that a piece of content – e.g., a blog post or image or video – be removed from an online platform implicates the free speech rights of the person who created that content. State and federal legislatures crafting laws (and courts applying and interpreting them) must consider the rights of that speaker, along with the rights of the subject of the speech in question and the role of the intermediary, in crafting appropriate remedies.

This paper offers a short legal primer describing the two major provisions of federal law – the “Digital Millennium Copyright Act” or “DMCA”, and the safe harbors embodied in Section 512 of the United States Copyright Act and Section 230(c) of the “Communications Decency Act” or “CDA” – that govern liability and immunity of online intermediaries in the United States, and the common law provisions that fill gaps not addressed by these two statutory regimes. After mapping the landscape for intermediary liability in the US, the paper turns to a series of case studies that highlight how a range of actors in various sectors of the Internet ecosystem have grappled with intermediary liability concerns in addressing their business and related needs. These case studies demonstrate both the importance and the limitations of existing intermediary liability regimes and the creative ways in which companies and others have worked within (and around) existing law to allocate liability in ways that work for them. Finally, the paper turns to a discussion of the role of transparency for intermediaries attempting to balance the competing interests described above and the need to maintain positive relationships with both the public and their user base.

II. Legal Landscape Primer

A. General Content Liability

1. Traditional Defamation Liability for Intermediaries

Publishing a false factual statement about a person that harms their reputation can lead to a civil (and, extremely rarely, criminal[1]) claim of defamation.[2] Defamation has a complicated structure; the tort evolved from the common law of the individual states, with a series of United States Supreme Court cases adding some specific, nationwide carve-outs and requirements deemed to be necessary in light of the First Amendment.[3] The law still varies considerably across each state, but to make out a claim of defamation today a plaintiff generally needs to show, among other things, (1) that a defendant published a statement; (2) that the statement was a false statement of fact (as opposed to true facts or an opinion); and (3) that the defendant acted with a certain level of fault (depending on the person involved, either negligence or “actual malice,” a term of art roughly meaning the defendant knew the statement was false at the time it was published).[4]

Claims against content intermediaries need to satisfy these elements as well, but any party against whom all of the elements of a defamation claim exist is potentially liable.[5] Prior to the advent of the Internet, courts limited the universe of possible defendants by requiring that an intermediary only be held liable if they “know[] or ha[ve] reason to know” of the statement’s defamatory character.[6]

This leads to different results based on different intermediaries in the offline world. Newspapers and magazines tend to be held responsible for their content, even when the content clearly owes its origin to a third party – e.g., with a letter to the editor.[7] The opposite result is usually reached when considering contract printing shops or “vanity presses.”[8] Those who distribute or host physical copies of defamatory publications are usually protected for the same reason, and scholars openly question whether a library or bookseller could ever be held liable for distributing defamatory books, even if they had reason to know of the book’s character.[9] Telegraph and telephone companies have generally been protected against claims for transmitting defamatory statements, though often with a stated exception for when the company knew of the message’s defamatory nature.[10]

Radio and television stations are generally held responsible for pre-recorded content, but live broadcasting presents a curious analytical challenge, as the station may not have the time to harbor any knowledge of a statement’s defamatory and false nature between when it is spoken and when it is aired.[11] At least one court has held that open solicitation of content without a broadcast delay system could lead to liability under a recklessness standard,[12] but most other courts take the opposite approach.[13]

Even when an intermediary publisher or conduit is held responsible for the content it is disseminating, other doctrines in defamation law provide protection to avoid inappropriate results. States adopt variations on a “fair report privilege,” which allows for the fair and accurate republication of statements made in official public documents or proceedings.[14] Many states also provide a “wire service defense,” which allows for the republication of defamatory content from a reputable news agency, provided the re-publisher did not know or have reason to know the information was defamatory and did not substantially alter the content.[15] Some states have also adopted a “neutral reportage” defense, to protect the republication of statements that are worthy of public discussion because they were made, even if the re-publisher believes them to be false – e.g., a wild allegation made by one politician against another during an election.[16] Such defenses, in particular cases, could extend to intermediaries hosting or republishing the content of others.

In the early days of Internet’s widespread adoption, commentators and cases sought to analogize re-publisher and distributor liability when considering bulletin boards and other online content platforms.[17] After one court assigned liability for the Internet service provider Prodigy Services Co. for content on one of its bulletin boards, based on the fact that Prodigy exercised general editorial control over the platform, Congress opted to define a different standard for online intermediary liability.[18]

[1] See David Pritchard, Rethinking Criminal Libel: An Empirical Study, 14 Comm. L. & Policy 303, 313 (2009) (finding 2-9 prosecutions a year in the state of Wisconsin, but noting this to be significantly a significantly higher rate than commonly thought). The Media Law Resource Center reported no criminal defamation cases in 2013. See New Developments 2013, Media L. Resource Ctr. Bulletin 90 (December 2013).

[2] See generally http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/defamation.

[3] Robert C. Post, The Social Foundation of Defamation Law: Reputation and the Constitution, 74 Cal. L. Rev. 691 (1986).

[4] Parties must also show that the statement was about the plaintiff and that the statement harmed the plaintiff’s reputation. Most states also require a plaintiff to show that they suffered “actual damages” based on the statement, or that the statement falls into one of several categories where damages are presumed. See Defamation, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/defamation (last updated Aug. 12, 2008). When discussing public officials and figures, the First Amendment case law requires a plaintiff to show that the defendant acted with “actual malice,” a term of art meaning that the defendant knew the statement was false when they published it, or acted with reckless disregard of the truth. For more on private and public figures, see Proving Fault: Actual Malice and Negligence, Digital Media Law Project http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/proving-fault-actual-malice-and-negligence (last updated Aug. 7, 2008). There are other overlapping claims that may be asserted in conjunction with defamation, but they are usually confined to the same general requirements as to falsity and fault. See Other Falsity-Based Legal Claims, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/other-falsity-based-legal-claims (last updated Aug. 15, 2008).

[5] Rodney Smolla, Law of Defamation § 4:87.

[6] Restatement (Second) Torts § 581. This scienter requirement has now spread to all claims of defamation through Supreme Court precedent, but nevertheless serves as a useful heuristic for separating parties traditionally liable for defamation from those who were not. See Smolla, supra note [[x]], at § 4:92.

[7] Sack on Defamation § 7.1; Marc A. Franklin, Libel and Letters to the Editor: Toward an Open Forum, 57 U. Colo. L. Rev. 651 (1986).

[8] Sack on Defamation § 7.3.4.

[9] Sack on Defamation § 7.3.4 (“Suppose a person were to inform public libraries and news vendors that a book, newspaper, or newsmagazine they are distributing contains false and defamatory statements . . . . May the libraries or vendors then be held liable for continuing to sell or circulate the offending material? That is possible, although the potential for use of that tactic to turn financially vulnerable distributors into censors . . . argues strongly for a complete distributors’ immunity from suit.”); Prosser and Keeton on Torts § 113 (1984) (“It would be rather ridiculous, under most circumstances, to expect a bookseller or a library to withhold distribution of a good book because of a belief that a derogatory statement contained in the book was both false and defamatory . . . .”); Loftus E. Becker, Jr., The Liability of Computer Bulletin Board Operators for Defamation Posted by Others, 22 Conn. L. Rev. 203, 227 (1989) (“[N]o one seems to have sued a library for defamation in this century.”). For an example of a case that held a bookseller liable based on this theory, see Janklow v. Viking Press, 378 N.W.2d 875 (S.D. 1988); Restatement (Second) Torts § 581 cmt. e (acknowledging possible liability for libraries and bookstores in exceptional cases).

[10] See Liability of Telegraph or Telephone Company for Transmitting or Permitting Transmission of Libelous or Slanderous Messages, 91 A.L.R.3d 1015 (1979) (citing numerous cases where courts applied the Restatement’s knowledge requirement or found categorical immunity for telegraph and telephone companies). Courts acknowledge the policy reasons for giving telegraph companies the leniency in deciding whether they should have known that a dispatch was defamatory. Gray v. W. Union Tel. Co., 13 S.E. 562 (Ga. 1891); but see Paton v. Great N.W. Tel. Co., 170 N.W. 511 (Minn. 1919) (finding potential liability for telegraph company for transmission).

[11] See Sack on Defamation § 7.3.5.A.2.

[12] Snowden v. Pearl River Broad. Corp., 251 So. 2d 405 (La. Ct. App. 1971).

[13] Sack on Defamation § 7.3.5.A.2 n. 66 (gathering cases).

[14] See Fair Report Privilege, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/fair-report-privilege (last updated July 22, 2008).

[15] Wire Service Defense, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/wire-service-defense (last updated July 22, 2008).

[16] See Neutral Report Privilege, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/neutral-report-privilege (last updated July 22, 2008); Sack on Defamation § 7.3.5.D.

[17] See, e.g., Becker, supra note [[x]].

[18] See David Ardia, Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: an Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, 43 Loyola of L.A. L. Rev., 373, 407-11 (2010) (chronicling the history of the lead-up to Section 230, including the Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Servs. Co., 1995 WL 323710 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. May 24, 1995)).

2. Traditional Privacy Liability for Intermediaries

Privacy laws in the United States consist of a patchwork of common law torts and specific statutory enactments, overlaid with nationwide exceptions made in light of the First Amendment.[19] Intermediaries primarily concern themselves with privacy law to the extent it impacts their own businesses operations and practices – for example, how they represent their data handling practices to the public, and how they handle their own data security.

A second form of privacy liability for intermediaries stems instead from the actions taken on behalf of others, and whether the intermediary can ever be held liable for contributing (willingly or not) to those actions. The laws around such invasions of privacy can be generally clustered into two categories: those that address the unlawful gathering of information (e.g., intruding into one’s private spaces or unlawfully recording conversations), and those that address publishing private information (e.g., the “public disclosure of private facts” tort or publishing specific information proscribed by statute[20]). The First Amendment plays a role in this space by both limiting the universe of defendants for intrusion claims[21] and by substantially limiting the types of claims that can be brought regarding the disclosure of private information.[22]

With respect to information gathering, many states recognize a tort called “intrusion upon seclusion,” which punishes one who intrudes into the solitude or seclusion of another in a way that is highly offensive to a reasonable person.[23] Because the defendant’s conduct usually must be intentional for liability to attach, it is rare to see liability extend to disinterested intermediaries.[24] At least one court has found secondary liability could attach to a newspaper for running a classified ad that facilitated intrusion of another, though in that case the plaintiff pleaded that the newspaper published the ad with the intent to invade the plaintiff’s privacy.[25]

Some intrusion laws attempt to indirectly target intrusion by punishing those who later disclose or receive the information that was unlawfully acquired. But First Amendment doctrine prevents the application of such laws to those who did not actively participate in the unlawful acquisition, at least when the information is true and a matter of public concern.[26] This would seem to preclude most information intermediaries from liability for transmitting content that was unlawfully acquired by others.

Laws concerning the disclosure of private information directly can vary considerably, but most states have some form of the tort called “public disclosure of private facts,” which concerns the intentional disclosure to the public[27] of non-newsworthy information about an individual that is highly offensive to a reasonable person.[28]

Unlike defamation or intrusion, the specific mental state of defendants varies considerably between states, so the mens rea does not generally limit liability for disinterested intermediaries in the same way as other torts.[29] That said, the few cases that consider a distributor’s liability tend to impart the same requirement from defamation cases that the distributor know the information to be tortious in order to be held liable.[30] Also, information obtained from public sources are considered protected under the First Amendment,[31] and republishing content originally published widely by others does not lead to liability in most cases, as the fact that the content was published previously means that the information is no longer considered private.[32]

The traditional standards for intermediary liability in privacy are applied in a radically different manner online, in large part due to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which is discussed in the following section.

[19] Daniel J. Solove & Paul M. Schwartz, Information Privacy Law 77 (3d ed. 2009).

[20] For an example of this, see 18 U.S.C. § 2710 (governing when and how a customer’s video rental history may be disclosed).

[21] See notes x–y, infra, and accompanying text.

[22] While the states that recognize a public disclosure tort include a definitional balance that precludes claims against newsworthy information, the Supreme Court has yet to directly consider a challenge to public disclosure torts in other cases. See Geoffrey R. Stone, Privacy, the First Amendment, and the Internet, in The Offensive Internet (Saul Levmore & Martha C. Nussbaum eds. 2010). For more on the history of balancing between free speech and privacy has had a complicated century of history. See Geoffrey R. Stone, Anthony Lewis, Freedom for the Thought That we Hate 59-80 (2009).

[23] Restatement (Second) Torts § 652B.

[24] See, e.g., Marich v. MGM/UA Telecomm., Inc., 113 Cal. App. 4th 415 (2003) (defining intent for California’s intrusion tort). For examples of cases where parties were liable as aiders or abettors of another’s intrusion, see David A. Elder, Privacy Torts § 2:9.

[25] Vescovo v. New Way Enters., Ltd., 60 Cal. App. 3d 582 (1976).

[26] See, e.g., Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514, 526 (2001) (The First Amendment prevents a radio broadcaster from being punished for disclosing the contents of an unlawfully-intercepted communication); Smith v. Daily Mail Publ'g Co., 443 U.S. 97, 104 (1979); Food Lion, Inc. v. Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 194 F.3d 505 (4th Cir. 1999) (refusing to escalate damages for breach of duty of loyalty based on subsequent disclosure of information); Doe v. Mills, 536 N.W.2d 824 (Mich. 1995) (knowing receipt of information unlawfully obtained does not lead to intrusion claim for the recipient). Scholars have been mindful to point out that the exact meaning and scope of the “Daily Mail principle” is not entirely clear. Janelle Allen, Assessing the First Amendment as a Defense for Wikileaks and Other Publishers of Previously Undisclosed Government Information, 46 U.S.F. L. Rev. 783, 798 (2012).

[27] This is deliberately made a wider audience than defamation, for which liability attaches when a statement is “published” to a single person. Restatement (Second) Torts § 652D cmt. a.

[28] Restatement (Second) Torts § 652D.

[29] David A. Elder, Privacy Torts § 3:7.

[30] See, e.g., Steinbuch v. Hachette Book Grp., 2009 WL 963588 at 3 (E.D. Ark. April 8, 2009); Lee v. Penthouse Int’l Ltd., 1997 WL 33384309 at 8 (C.D. Cal. March 19, 1997).

[31] See, e.g., The Florida Star v. B.J.F., 491 U.S. 524 (1989).

[32] See, e.g., Ritzmann v. Weekly World News, 614 F. Supp. 1336 (N.D. Tex. 1985); Heath v. Playboy Enters., Inc., 732 F. Supp. 1145 (S.D. Fla. 1990); but see Michaels v. Internet Ent. Grp., Inc., 5 F. Supp. 2d 823 (C.D. Cal. 1998) (disclosure of more than the ways originally revealed in first publication can give rise to claim for republication).

3. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

As noted in the preceding sections, liability for offline content distributors or hosts largely turns on whether the host knows or has reason to know that they are hosting tortious content. In the earliest days of the Internet, courts used these standards to assess liability of online intermediaries, but found that the law created a perverse result. Online intermediaries possessed the technical ability to filter or screen content in the way an offline intermediary never could, but under existing standards this meant that the intermediary would assume liability for all the content over which they had supervisory control. In the most famous case on point, this included a service that was trying specifically to curate a family friendly environment, at a time when the public was greatly concerned about the adult content on the Internet.[33] In order to “to promote the continued development of the Internet and other interactive computer services and other interactive media [and] to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet and other interactive computer services,” Congress enacted Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.[34]

Section 230 prevents online intermediaries from being treated as the publisher of content from users of the intermediaries. By the terms of the statute, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” [35] An “interactive computer service” under Section 230 is defined as “any information service, system, or access software provider that provides or enables computer access by multiple users to a computer server . . . ”[36] Online intermediaries of all sorts meet this definition, including Internet service providers, social media websites, blogging platforms, message boards, and search engines.[37] An “information content provider” in turn is defined as “any person or entity that is responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.”[38]

Section 230 covers claims of defamation, invasion of privacy, tortious interference, civil liability for criminal law violations, and general negligence claims based on third-party content,[39] but it expressly excludes federal criminal law, intellectual property law, and the federal Electronic Communications Privacy Act or any state analogues.[40] Its terms also specify that the coverage is for “another’s” content, thus not protecting statements published by the interactive computer service directly.[41] Thus, to apply Section 230’s protection, a defendant must show (1) that it is a provider or user of an interactive computer service; (2) that it is being treated as the publisher of content (though not with respect to a federal crimes, intellectual property, or communications privacy law); and (3) that the content is provided by another information content provider.

The law was designed in part to foster curation of online content, and courts have found that a wide array of actions can be taken by “interactive computer services” over third-party content are covered by Section 230. These include basic editorial functions, such as deciding whether to publish, remove, or edit content;[42] soliciting users to submit legal content;[43] paying a third party to create or submit content;[44] allowing users to respond to forms or drop-downs to submit content;[45] and keeping content online even after being notified the material is unlawful.[46] This applies to both claims rooted in defamation and those rooted in invasion of privacy.[47]

On the other hand, if the intermediary creates actionable content itself, it will be liable for that content.[48] Courts are also unlikely to find that Section 230 applies when an interactive computer service edits the content of a third party and materially altering its meaning to make it actionable;[49] requires users to submit unlawful content;[50] or if the service promises to remove material and then fails to do so.[51] When an intermediary takes these actions, it is deemed to have “developed” the content by “materially contributing to the alleged illegality of the conduct.”[52]

While stated very simply, the law upsets decades of precedent in the areas of content liability law, and radically alters the burdens on online services for claims based on user content.[53] By limiting any assumed liability for a wide range of content-based claims (and given the other content areas discussed below), Section 230 effectively removes any duty for an interactive computer service to monitor content on its platforms, a tremendous boon for the development of new intermediaries and services.[54] Virtually all liability for content-based torts is pushed from the service to others, often the user. In practical terms, however, this has yet to manifest a windfall for online services; many claims are still brought against online intermediaries, and the question is often litigated extensively and at great expense before courts find that claims are invalid.[55]

As noted above, Section 230 does not cover intellectual property laws, and thus different rules apply in these cases. These are now addressed.

[33] Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Servs. Co., 1995 WL 323710 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. May 24, 1995). See also Lawrence Lessig, Code 2.0 249-52 (2006) (discussing the Internet anti-pornography efforts happening around the time of the Communications Decency Act debate).

[34] 47 U.S.C. § 230. The section was part of a greater law that sought to relegate the transmission of offensive content to minors, the majority of which was later struck by the Supreme Court. See Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844 (1997).

[35] 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1).

[36] § 230(f)(2).

[37] See Ardia, supra note [[x]], at 387-89.

[38] § 230(f)(3).

[39] See Ardia, supra note [[x]], at 452.

[40] § 230(e)(1)–(4). The Electronic Communications Privacy Act governs the voluntary and compelled disclosure of electronic communications by electronic communications services.

[41] See § 230(c)(1).

[42] See Donato v. Moldow, 865 A.2d 711 (N.J. Super. Ct. 2005).

[43] See Corbis Corporation v. Amazon.com, Inc., 351 F.Supp.2d 1090 (W.D. Wash. 2004); see also Global Royalties, Ltd. v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 544 F. Supp. 2d 929, 933 (D. Ariz. 2008) (holding that even though a website “encourages the publication of defamatory content,” the website is not responsible for the “creation or development” of the posts on the site).

[44] See Blumenthal v. Drudge, 992 F. Supp. 44 (D.D.C. 1998).

[45] See Carafano v. Metrosplash.com, 339 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2003).

[46] See Zeran v. America Online, Inc., 129 F.3d 327 (4th Cir. 1997). Promising to remove content and then declining to do so, however, can expose an interactive computer service to liability. See Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc., 570 F.3d 1096 (9th Cir. 2009). For more examples of actions likely to be covered under Section 230, see Online Activities Covered by Section 230, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/online-activities-covered-section-230 (last updated Nov. 10, 2011).

[47] See, e.g., Jones v. Dirty World Entertainment Recordings, LLC, 2014 WL 2694184 (6th Cir. 2014) (defamation claim preempted by Section 230); Doe v. Friendfinder Network, 540 F. Supp. 2d 288, 302–303 (D.N.H. 2008) (intrusion upon seclusion and public disclosure of private facts claims preempted).

[48] See MCW, Inc. v. Badbusinessbureau.com, LLC, 2004 WL 833595, No. 3:02-CV-2727-G at * 9 (N.D. Tex. April 19, 2004) (the operator of a website may be liable when it is alleged that “the defendants themselves create, develop, and post original, defamatory information concerning” the plaintiff).

[49] See Online Activities Not Covered by Section 230, Digital Media Law Project, http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/online-activities-not-covered-section-230 (last updated Nov. 10, 2011).

[50] See Fair Housing Council v. Roommates.com, LLC, 521 F.3d 1157, 1175 (9th Cir. 2008) (en banc).

[51] See Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc, 570 F.3d 1096 (9th Cir. 2009).

[52] See Jones v. Dirty World Entertainment Recordings, LLC, 2014 WL 2694184 (6th Cir. 2014).

[53] See Ardia, supra note [[x]], at 411.

[54] See, e.g., Jack M. Balkin, Old-School/New-School Speech Regulation, 127 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 17 (2014) (“Section 230 immunity . . . ha[s] been among the most important protections for free expression in the United States in the digital age. [It] has made possible the development of a wide range of telecommunications systems, search engines, platforms, and cloud services without fear of crippling liability.”).

[55] Id. at 493.

B. Copyright

1. A General Overview of Secondary Liability for Copyright Infringement

In U.S. law, copyright liability comes in two main forms, “primary” or “direct” liability, and “secondary liability”.[56] The first, direct liability, is the liability that attaches to an actual infringer of the copyright(s) in question, whether by copying without authorization or by violating any of the other rights that copyright owners possess, as described in 17 U.S.C. 106 of U.S. law. Direct liability, although it can become more complex depending on the facts surrounding an alleged infringement, is generally quite straightforward. Either copyright was infringed or it wasn’t.

The second type of liability, secondary liability, is more nuanced, in large part because there is nothing in U.S. copyright statute that expressly provides for such liability. Secondary liability in the United States is therefore what is known as “judge-made” law, a set of rules and guidelines, rising out of other areas of liability law[57], that have accumulated over time on a case-by-case basis, that then exist as binding precedent. This makes secondary liability more fact specific and also potentially more prone to evolve based on changes in technology and normative behaviors.[58]

Within this framework, secondary liability is conceptualized as taking on one of two forms[59]: that resulting from “vicarious infringement” and that resulting from “contributory infringement.” Each version requires that there first be a direct infringement. The remaining differences are subtle but critical, especially with respect to the implicit incentives for potential secondary infringers, and address a potential secondary infringer’s “knowledge” of any direct infringement, the degree to which the infringer has the ability to control the direct infringement, and their financial benefit, if any. Each of these facets are critical to understanding the competing imperatives that online intermediaries (“OI”s) face, and it is with respect to OIs that this section’s further discussion will proceed.

[56] There are mentions in the literature and case law of a concept of “tertiary liability, “those who help the helpers”; see, e.g. Mark A. Lemley & R. Anthony Reese “Reducing Digital Copyright Infringement Without Restricting Innovation” 56 Stan. L. Rev. 1345, 1345-54, 1373-1426 (2004); Benjamin H. Glatstein “Tertiary Copyright Liability” The University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 71, No. 4 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 1605-1635, as well as Eric Goldman “Offering P2P File-Sharing Software for Downloading May Be Copyright Inducement–David v. CBS Interactive” http://blog.ericgoldman.org/archives/2012/07/inducement_as_a.htm (discussing how courts may view P2P filesharing as a special case) but this theory of liability has typically been dismissed as representing too diffuse a chain of causality, and unsupported by case law.*

[57] See, e.g., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005), 930 (2005).: “[T]hese doctrines of secondary liability emerged from common law principles and are well established in the law.” (quoting Blackmun’s dissent in Sony).

[58] “[T]he lines between direct infringement, contributory infringement, and vicarious liability are not clearly drawn”

Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 435(1984).

[59] Pamela Samuelson has hypothesized that the “active inducement” theory laid out in the MGM Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005), case may amount to a new form of secondary liability. See Pamela Samuelson,

Three Reactions to MGM v. Grokster, 13 Mich. Telecomm. Tech. L. Rev. (2006).

i. Contributory Infringement

For an OI to be liable for “contributory infringement,” the OI must have actual or constructive knowledge of the direct infringement[60] and make a “material contribution” to the direct infringement as well.[61] As can easily be imagined, cases on this turn on the nature of “knowledge” and what sort of contribution is “material”. For example, in Perfect 10 v. Visa International,[62] the majority found that the role of credit card companies in processing payment transactions for infringing material was too attenuated from the infringing activity to be considered a "material contribution."[63] With respect to knowledge, ignorance of the direct infringement does not necessarily immunize an OI to a claim of secondary liability, since courts have also introduced the idea of “willful blindness”[64] for situations in which a defendant “should have” known about the direct infringement, but deliberately chose not to know about it, or at least to not take notice oo act upon facts or circumstances that pointed into the direction of infringement.

Important cases addressing contributory infringement, especially with respect to online intermediaries, are Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., and the recently settled Viacom International, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc.[65] Critically for OIs whose business model or technology may involve copyright infringement, but may also be used in non-infringing ways, the Sony case gave rise to the “substantial non-infringing uses” test, borrowed from patent law’s “staple article” doctrine, with respect to intermediary technologies that only make direct infringement possible rather than definite. [66]

The court in Sony held that in the case of an infringer selling a technology that makes infringement possible, (here, through copying) if a substantial non-infringing use for the technology exists, then the vendor of the technology cannot be found liable[67] because constructive knowledge of the (potential) direct infringement cannot and should not be imputed to the OI. However, the Grokster case expanded on and modified this theory, holding that simply because an OI’s technology was merely capable of substantial non-infringing uses did not categorically immunize the OI from liability, and that contributory liability may still be found if there is clear evidence of an OI’s intent to induce and facilitate infringement.[68] This has become known as the Grokster “inducement rule.”[69]

[60] Compare the DMCA’s “actual knowledge” requirement 17 USC 512(c)(1)(A)(i)

[61] The classic case on this topic is Fonovisa, Inc. v. Cherry Auction, Inc., 76 F.3d 259, 264 (9th Cir. 1996), although this does not have to do with OIs. The lodestar case for OIs is now Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005), which also adopted the doctrine of “inducement” for copyright liability.

[62] 494 F.3d 788 (9th Cir. 2007)

[63] “Copyright: Infringement Issues - Internet Law Treatise,” accessed June 18, 2014, https://ilt.eff.org/index.php/Copyright:_Infringement_Issues.

[64] In re Aimster Copyright Litigation 334 F.3d 643, 650 (C.A.7 (Ill.),2003) (“Willful blindness is knowledge, in copyright law (where indeed it may be enough that the defendant should have known of the direct infringement”)

[65] See: <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/19/business/media/viacom-and-youtube-settle-lawsuit-over-copyright.html>

[66] Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. 464 U.S. 417, 442 (1984)

[67] “The so-called “Sony safe harbor”. See (“the sale of copying equipment, like the sale of other articles of commerce, does not constitute contributory infringement if the product is widely used for legitimate, unobjectionable purposes. Indeed, it need merely be capable of substantial noninfringing uses.”)

[68] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 934-935 (2005) (“Thus, where evidence goes beyond a product's characteristics or the knowledge that it may be put to infringing uses, and shows statements or actions directed to promoting infringement, Sony's staple-article rule will not preclude liability.”); See also Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. v. Fung, 710 F.3d 1020 (9th Cir. 2013)

[69] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 936-937 (2005) (“[O]ne who distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright, as shown by clear expression or other affirmative steps taken to foster infringement, is liable for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties.”)

ii. Vicarious Infringement

For an OI to be liable for vicarious infringement, it must benefit financially from the direct infringement and have both the right and ability to supervise the direct infringer,[70] a concept rooted in the “respondeat superior” doctrine of agency law. Critically for OIs, especially those that are so large that they cannot monitor all the content that they host or is under their purview, actual knowledge of the infringing conduct is not a requirement.[71] It is the OI’s ability to supervise the direct infringer that becomes dispositive.

Whether or not an OI has benefitted financially from another’s direct infringement may seem like a clear dichotomy. There must be a “causal relationship between the infringing activity and any financial benefit [the] defendant reaps.”[72] However, this question has become quite nuanced with respect to the many disparate revenue streams that attach to an OI. As just one example, if an OI hosts third party content, and typically serves advertisements next to that content, for which the OI receives payments, and the content in question proves to infringe copyright, the revenue from that advertising may well be enough to render the OI liable,[73] whether those advertisements appear automatically or are curated.

Whether an OI has the ability to supervise the direct infringer is a fact-specific question, focusing on the relationship between the direct infringer and the would-be secondary infringer. Key cases here are Fonovisa v Cherry Auction,[74] where a flea market was held liable for a vendor’s infringing sales and A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.[75] So far, most definitions of “supervision” have been imported from non-Internet fact patterns[76], and no online-specific variation of what it means to be able to “supervise” that might be uniquely applicable to OIs has emerged from the case law. Note, though, that the U.S. Supreme Court in Grokster described an OI’s failure to deploy “filtering tools or other mechanisms to diminish the infringing activity using their software” as giving added significance to other evidence of unlawful objectives and "underscore[ing] Grokster's and StreamCast's intentional facilitation of their users' infringement.”[77]

A final note on one of the most basic features of the modern Internet: linking.[78] Whether an OI, such as a search engine, link aggregator, or some other variety of OI can be held secondarily liable for merely linking to directly infringing material is typically described as “unsettled” law.[79] Certainly rights holders, especially large institutional ones, would like to be able to sue wealthy OIs rather than individuals for damages, and OIs who link to content would prefer to be shielded from liability if that content turns out to infringe, but courts have described both a “general principle that linking does not amount to copying,” and stated that “Although hyper-linking per se does not constitute direct copyright infringement because there is no copying, in some instances there may be a tenable claim of contributory infringement or vicarious liability.”[80] The Supreme Court has also, in a longer discussion of “inducement,” unfavorably mentioned providing links to known infringing content.[81] Compare the 2014 European Court of Justice ruling that linking to publicly available material is not infringement, but that linking to restricted or unauthorized material may well be.[82]

[70] Compare 47 U.S.C §230(f)(3)’s “responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.” as well as 47 U.S.C §230(f)(4); See Grokster, 545 U.S. at 930, for a variant of the definition. (“One ... infringes vicariously by profiting from direct infringement while declining to exercise a right to stop or limit it.”)

[71] 3 Nimmer § 12.04[A][1].

[72] “It may also be established by evidence showing that users are attracted to a defendant's product because it enables infringement, and that use of the product for infringement financially benefits the defendant. “Arista Records LLC v. Lime Grp. LLC, 784 F. Supp. 2d 398, 435 (S.D.N.Y. 2011)

[73] Columbia Pictures Indus. v. Gary Fung, 710 F.3d 1020 (“Under these circumstances, we hold the connection between the infringing activity and Fung's income stream derived from advertising is sufficiently direct to meet the direct "financial benefit" prong of § 512(c)(1)(B).). but see Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 487 F.3d 701, 730 C.A.9 (Cal.), (2007) (Google’s ability to terminate an AdSense partnership did not amount to a right or ability to control an infringing AdSense participant.)

[74] Fonovisa v. Cherry Auction, 76 F. 3d 259 (9th Cir. 1996).

[75] “Fonovisa essentially viewed “supervision” in this context in terms of the swap meet operator's ability to control the activities of the vendors, 76 F.3d at 262, and Napster essentially viewed it in terms of Napster's ability to police activities of its users, 239 F.3d at 1023.” Perfect 10, Inc. v. Visa Intern. Service Ass'n 494 F.3d 788, 802 (C.A.9 (Cal.),2007)

[76] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster Ltd. 380 F.3d 1154, 1164 -1165 (C.A.9 (Cal.), 2004) (“A salient characteristic of that relationship often, though not always, is a formal licensing agreement between the defendant and the direct infringer”) (internal cites omitted)

[77] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 939, 125 S. Ct. 2764, 2781, 162 L. Ed. 2d 781 (2005)

[78] C.f. 17 U.S.C. 512(d)’s “information location tools”

[79] “Copyright: Infringement Issues - Internet Law Treatise.”

[80] Online Policy Grp. v. Diebold, Inc., 337 F. Supp. 2d 1195, 1202 n.12 (N.D. Cal. 2004) ( referencing as notable the DMCA’s 512(d).)

[81] Columbia Pictures Indus., Inc. v. Fung, 710 F.3d 1020, 1036-1038 (9th Cir. 2013) cert. dismissed, 134 S. Ct. 624, 187 L. Ed. 2d 398 (U.S. 2013)

[82] http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=147847&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=req&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=7778 “On the other hand, where a clickable link makes it possible for users of the site on which that link appears to circumvent restrictions put in place by the site on which the protected work appears in order to restrict public access to that work to the latter site’s subscribers only, and the link accordingly constitutes an intervention without which those users would not be able to access the works transmitted, all those users must be deemed to be a new public, which was not taken into account by the copyright holders when they authorised the initial communication, and accordingly the holders’ authorisation is required for such a communication to the public. This is the case, in particular, where the work is no longer available to the public on the site on which it was initially communicated or where it is henceforth available on that site only to a restricted public, while being accessible on another Internet site without the copyright holders’ authorisation.”).

2. The DMCA’s Safe Harbor

Section 512(c) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, “Limitations on liability relating to material online,” provides for four separate sets of circumstances in which a “service provider”[83] “shall not be liable for monetary relief.” This shield from liability has come to be known as the DMCA’s “safe harbor”, and these four circumstances are: transitory digital communications, system caching, information residing on systems or networks at direction of users, and information location tools. Of these, the latter two are most germane to a discussion of online intermediaries. It is the “user” explicitly referenced in the “direction of users” that renders the service provider an intermediary, and “information location tools” involve a provider “referring or linking users to an online location”.

In each case, the protection from liability that an OI can enjoy is predicated on meeting certain conditions. To enjoy 512(c) immunity regarding infringing “information residing on an OI’s system or network at the direction of a user”, it must be true that the OI:

- (A)(i) does not have actual knowledge that the material or an activity using the material on the system or network is infringing;

- (ii) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

- (iii) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to the material;

- (B) does not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity, in a case in which the service provider has the right and ability to control such activity; and

- (C) upon notification of claimed infringement as described in paragraph (3), responds expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material that is claimed to be infringing or to be the subject of infringing activity.

Note the inclusion of the phrases that are similar to the requirements in the two forms of secondary liability. To summarize, an OI is not liable for monetary damages or for injunctive relief, except for the specific types of the latter outlined in 512(j), or for any (allegedly) infringing material on their systems or networks unless they know or have been told it is there and have failed to remove it. It is important to note that if the material in question is not removed, that does not render the OI liable, it simply means they could be found liable, whereas if the material in question is removed, there can be no liability regardless of the outcome of a suit against the user.

The language describing the conditions for Section 512(d)’s safe harbor are virtually identical to those in 512(c), in fact using identical language to that of 512(c) regarding notifications, simply clarifying the new variety of information to which the notification refers.[84] It is a DMCA notice submitted under 512(d) that leads to results being removed from Google Search. There are a also few further requirements described in 512(i) that apply to all of Section 512’s safe harbors. An OI should have a “repeat infringer policy” that aims to terminate users of the service that repeatedly infringe and an OI should also accommodate and not interfere with “standard technical measures.” In short, an online intermediary can enjoy the Section 512(c) and (d) “safe harbor” and avoid all liability for any copyright infringement committed by its users as long as it expeditiously removes allegedly infringing material once notified of that material’s presence, and fulfills Section 512’s requirements that apply to all safe harbors. However, the OI may still be subject to the injunctions described in 512(j).

The system’s general weighting is therefore toward easy and unquestioned removal. Section 512(f)’s penalties for a sender’s misrepresentation in a notice apply only when the misrepresentation is material and knowing, and even then, the only available penalties are attorneys’ fees.[85] Section 512(g) absolves the OI from any liability for mistakenly removing material as long as it was done in good faith; under 512(g)(3) a counter-notice sender must swear on penalty of perjury that the material was removed in error; and even in the event of a counter-notice, restoring material that has been removed can happen only after a 10 day period.

[83] 17 U.S.C. 512(k) (“(1) Service provider. — (A) As used in subsection (a), the term “service provider” means an entity offering the transmission, routing, or providing of connections for digital online communications, between or among points specified by a user, of material of the user's choosing, without modification to the content of the material as sent or received.

(B) As used in this section, other than subsection (a), the term “service provider” means a provider of online services or network access, or the operator of facilities therefor, and includes an entity described in subparagraph (A).”

[84] 512(d)(3) upon notification of claimed infringement as described in subsection (c)(3), responds expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material that is claimed to be infringing or to be the subject of infringing activity, except that, for purposes of this paragraph, the information described in subsection (c)(3)(A)(iii) shall be identification of the reference or link, to material or activity claimed to be infringing, that is to be removed or access to which is to be disabled, and information reasonably sufficient to permit the service provider to locate that reference or link.”

[85] The standard for misrepresentation is quite high as it requires “actual knowledge” of misrepresentation on the part of the copyright owner: Rossi v. Motion Picture Association of America, Inc., 391 F.3d 1000 (9th Cir. 2004), 1005 (2004).: “A copyright owner cannot be liable simply because an unknowing mistake is made, even if the copyright owner acted unreasonably in making the mistake.”

C. Other Intellectual Property Laws

1. Trademark

Trademarks are words, phrases, symbols, and other indicia used to identify the source or sponsorship of goods or services. The law allows trademark owners to prevent commercial uses by others that would likely cause customer confusion. Trademark law is recognized at the federal level in the Lanham Act, and every state has an analogous trademark or “unfair competition” law.[86]. To establish ownership of a mark, an aspiring trademark owner must use their trademark in commerce in connection with goods or services.[87]

After ownership is established, the Lanham Act authorizes an owner to bring lawsuits to prevent others from using the mark in a manner that would confuse consumers, or, with respect to more famous marks, to “dilute” mark’s distinctiveness across all goods and services.[88] Defenses to a claim of trademark infringement or dilution include that the defendant was selling the plaintiff’s genuine goods,[89] that the defendant was using the words that make up the plaintiff’s trade name for their normal meaning,[90] and that the defendant was using the plaintiff’s mark to refer to the plaintiff directly.[91]

Trademark law is unique in this study, as there is no equivalent to general content liability’s Section 230 or copyright’s Section 512 “safe harbor” to address online intermediary liabilities. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act does not protect online intermediaries from trademark liability under the Lanham Act,[92] and courts are split as to whether it protects against claims under state trademark laws.[93] As a result, much of recent trademark law reflects a judicial attempt to reinterpret existing tests in light of online activity, which has led to less legal certainty. Because trademark draws from both state and federal laws, precedent in this area is especially complex.

Existing Supreme Court precedent recognized secondary trademark liability for those who intentionally induce another to infringe a trademark, as well as those who manufacture or distribute supplies to another, knowing that person is engaging in trademark infringement.[94] Lower courts have extended that to cases where the defendant supplies a platform for the sale of trademark-infringing goods, such as the operator of a flea market, when a plaintiff can show that platform operator knew about infringing activity. These courts, however, have not imposed an affirmative duty to take precautions against counterfeits.[95]

Applying these principles to the online context, courts generally agree that online intermediaries can be held liable for infringement, but establishing clear standards for that liability has been more divisive.[96] In one early case, a court stated that an Internet company could be liable under a theory of contributory trademark infringement if it possessed “direct control and monitoring” over the infringing activity of third parties on the site, though it declined to extend that theory to the defendant, a domain name resolution service.[97] In a prominent 2010 case, Tiffany v. eBay (discussed in the “Private Ordering to Respond to Trademark Concerns – eBay’s VERO Program” case study below) a federal appellate court upheld the infringement-management practices of the online auction website eBay, who took down infringements upon receipt of specific rights holder complaints.[98] Critically, the court held that general knowledge that the defendant’s platform was being used for infringing activity on the platform was not sufficient; plaintiffs would have to show that a defendant has knowledge of specific infringing conduct.[99] For online auction sites, the holding in Tiffany likely means increased industry homogeneity as competitors attempt to craft their own business as in the mold of eBay’s judicially accepted model. For other online intermediaries, the lack of a legal standard means increased risk and wary innovation. For an enterprising online intermediary with a service susceptible to a claim of contributory trademark infringement, looking to the policies and standards underlying the CDA and DMCA are likely the best barometers of legal guidance.[100]

[86] See State Trademark Information and Links, U.S.P.T.O., <http://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/process/State_Trademark_Links.jsp> (last updated July 24, 2012).

[87] See Restatement (Third) Unfair Competition § 18.

[88] See What Trademark Covers, Digital Media Law Project, <http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/what-trademark-covers> (last updated April 30, 2008). A trademark owner can also bring a claim of dilution by “tarnishment,” or the use of a trade name that harms the reputation of a famous mark. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(C).

[89] See, e.g., Prestonettes, Inc. v. Coty, 264 U.S. 359 (1924).

[90] This is sometimes called a “descriptive fair use.” See, e.g., KP Permanent Make-Up, Inc. v. Lasting Impression I, Inc., 543 U.S. 111 (2004).

[91] This is called a “nominative fair use, and tends to also include the requirement that the mark at issue must not be readily identifiable without use of the mark’s name, the use of the mark must be limited to as much as is necessary to identify the mark, and the user must do nothing that would suggest sponsorship or endorsement by the trademark owner. The New Kids on the Block v. News America Publ’g, Inc., 971 F.2d 302 (9th Cir. 1992). Critics note that this is, in effect, the same test as the general likelihood of confusion test. See William McGeveran, Rethinking Trademark Fair Use, 94 Iowa L. Rev. 49, 90-97 (2008).

[92] See, e.g., Parker v. Google, Inc. 442 F. Supp. 2d 492, 502 n.8 (E.D. Pa. 2006).

[93] Compare Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill, LLC 488 F.3d 1102, 1118-19 (9th Cir. 2007) (Section 230’s exception for “intellectual property” only covers federal intellectual property laws); with Doe v. Friendfinder Network, Inc., 540 F. Supp. 2d 288, 298-302 (D.N.H. 2008) (extensively analyzing Perfect 10 and deciding that Section 230 does extend to state intellectual property laws).

[94] Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 853-54 (1982).

[95] Hard Rock Cafe Licensing Corp. v. Concession Services, Inc., 955 F.2d 1143, 1149 (7th Cir. 1992); Fonovisa Inc. v. Cherry Auction Inc., 76 F.3d 259, 265 (9th Cir. 1996).

[96] See e.g., Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Network Solutions, Inc., 194 F.3d 980, 984 (9th Cir. 1999); Rescuecom Corp. v. Google Inc., 562 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2009); Playboy Ent., Inc. v. Netscape Comm’ns Corp., 354 F.3d 1020, 1024 (9th Cir. 2004); Tiffany (NJ) Inc. v. eBay Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2010); Rosetta Stone Ltd. v. Google, Inc., 676 F.3d 144, 149 (4th Cir. 2012).

[97] Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Network Solutions, Inc., 194 F.3d 980, 984 (9th Cir. 1999).

[98] Tiffany (NJ) Inc. v. eBay Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2d Cir. 2010).

[99] Id. at 107.

[100] At present, the most considerable legal attention to intermediaries has come not for actions they take with respect to user content, but to their own direct liability. This is in contrast to earlier times, where direct liability was rarely found with online service providers. Emily Favre, Online Auction Houses: How Trademark Owners Protect Brand Integrity Against Counterfeiting, 15 J.L. & Pol'y 165, 179 (2007). Two recent federal appellate cases have taken issue with Google’s AdWords program, which allows companies to buy advertisement to display alongside searches for certain words, including the names of competing companies. See Rescuecom Corp. v. Google, Inc., 562 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2009); Rosetta Stone Ltd. v. Google, Inc., 676 F.3d 144, 149 (4th Cir. 2012). Both cases subsequently settled.

2. Misappropriation and Right of Publicity Laws

Two overlapping types of laws govern the use of a person’s name or likeness for commercial or exploitative purposes without the person’s consent: right of publicity laws and laws against misappropriation of a person’s name or likeness.[101] While the two types of laws cover the same conduct, they are meant to remedy different harms: misappropriation is meant to remedy the damage to human dignity for unauthorized commercialization, while right of publicity is meant to compensate for commercial damage for lost licensing revenue.[102] Like the privacy torts discussed above, knowing participation in another’s violation could lead to intermediary liability, though there are very few cases on point.[103]

Courts unanimously agree that federal intellectual property claims are not covered by the CDA, but there is ongoing disagreement over whether the exception also extends to state intellectual property claims, particularly claims involving states’ right of publicity laws.[104] Other courts have taken the middle path, noting the difficulty of the issue and refusing to consider whether state intellectual property rights are exempted by the CDA when other means of settling the claim exist.[105] This echoes a concern articulated in the discussion of CDA 230 above: while Section 230 by its terms provides a clear and direct means for foreclosing intermediary liability, courts have allowed extensive and costly litigation on the question, undercutting its positive effects for intermediaries.[106]

[101] See generally Using The Name or Likeness of Another, Digital Media Law Project, <http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/using-name-or-likeness-another> (last updated July 30, 2008).

[102] J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition § 28:6 (4th ed. 2014).

[103] Perfect 10, Inc. v. Cybernet Ventures, Inc., 213 F. Supp. 2d 1146, 1183 (C.D. Cal. 2002) (finding a likelihood of success on an claim for aiding another’s right of publicity violation); but see Perfect 10, Inc. v. Visa Int’l Serv. Ass’n, 494 F.3d 788, 809 (9th Cir. 2007) (declining to find authority for a credit card processor for aiding and abetting a right of publicity violation, “[e]ven if such liability is possible under California law – a proposition for which [plaintiff] has provided no clear authority”); Keller v. Electronic Arts, Inc., No. 09-cv-1967, 2010 WL 530108 at * 2 (N.D. Cal. 2010) aff’d on other grounds sub nom. In re NCAA Student-Athlete Name & Likeness Licensing Litigation, 724 F.3d 1268 (9th Cir. 2013) (finding no theory of liability for those who enable another’s right of publicity violation).

[104] Compare Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill, LLC 488 F.3d 1102, 1118-19 (9th Cir. 2007) (Section 230’s exception for “intellectual property” only covers federal intellectual property laws); with Doe v. Friendfinder Network, Inc., 540 F. Supp. 2d 288, 298-302 (D.N.H. 2008) (extensively analyzing Perfect 10 and deciding that Section 230 does extend to state intellectual property laws).

[105] Almeida v. Amazon.com, Inc., 456 F.3d 1316 (11th Cir. 2006).

[106] See generally Ardia, supra note [[x]].

3. The Espionage Act

Because of the considerable attention given toward the dissemination of classified government information through the documents released by Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden, and the profound policy implications of both the information they conveyed and the treatment of those who handle and disseminate such documents to the public, special attention should be given to a particular federal crime that implicates the disclosure of classified information. The Espionage Act of 1917 contains many provisions intended to prohibit interference with military operations and protect national security.[107] These include provisions that criminalize obtaining, collecting, or communicating information that would harm the harm the national defense of the United States.[108] This section was used by the United States government to go after the New York Times and Washington Post for their publication of “The Pentagon Papers,” a classified and damning assessment of United States involvement in the Vietnam War.[109] Most recently, it was used to convict former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning for leaking classified documents to the organization WikiLeaks.[110]

While all federal criminal law includes the possibility for a charge of aiding and abetting another’s violation of the law,[111] the United States has never successfully prosecuted an information intermediary for disseminating classified information under the Espionage Act.[112] Such a theory would present profound First Amendment issues, and ultimately an intermediary may only be found liable if the intermediary bribed, coerced, or defrauded a government employee to disclose classified information.[113]

[107] See 18 U.S.C. §§ 793–798.

[108] 18 U.S.C. § 793(e).

[109] New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

[110] Cora Currier, Charting Obama’s Crackdown on National Security Leaks, Pro Publica, July 30, 2013, <http://www.propublica.org/special/sealing-loose-lips-charting-obamas-crackdown-on-national-security-leaks>. Many others have been charged but not ultimately convicted for violating the Espionage Act or conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act.

[111] 18 U.S.C. § 2; see also § 793(g) (“If two or more persons conspire to violate any of the foregoing provisions of this section, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each of the parties to such conspiracy shall be subject to the punishment provided for the offense which is the object of such conspiracy.”).

[112] See Emily Peterson, WikiLeaks and the Espionage Act of 1917: Can Congress Make It a Crime for Journalists to Publish Classified Information?, The New Media and the Law Vol. 35 No. 3, Summer 2011, available at <http://www.rcfp.org/browse-media-law-resources/news-media-law/wikileaks-and-espionage-act-1917>.

[113] See Geoffrey R. Stone, Government Secrecy vs. Freedom of the Press, 1 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 185, 217. For more on the general First Amendment right to disclose true matters of public concern, see supra notes x-y and accompanying text.

4. Surveillance Law

A patchwork of federal law enables both law enforcement and intelligence agencies to compel online intermediaries (as well as others) to disclose data about their users, sometimes including the content of their communications. The federal requirements for the disclosure of user data are mainly found in two places. The primary authority enabling the federal government to compel companies to surrender customer data in criminal investigations is found in the Stored Communications Act (SCA). The authority for intelligence investigations is found primarily in the Foreign Intelligence and Surveillance Act (FISA) and related amendments to the SCA. The authority used to compel the data disclosure is important for several reasons: it determines the legal standard that must be used, the kind of data that can be collected, and even how companies can write their transparency reports.

The SCA is an outdated law, enacted well before high-speed Internet or gigabytes of free cloud storage was the norm. The SCA gives law enforcement agencies the ability to collect substantial personal data, often with minimal court supervision. Under the framework of the SCA, there are three primary methods for compelling data collection: warrants, court orders, and subpoenas.

The easiest form of legal process to obtain is a subpoena. Instead of going before a court or a judge, a law enforcement agent can directly issue a subpoena to a company if there is any reasonable possibility that the materials will produce information relevant to the general subject of the investigation. Because it is so easy to obtain a subpoena, the types of information that law enforcement can obtain subject to a subpoena are fairly circumscribed. Using a subpoena, law enforcement can obtain what is known as “basic subscriber information.” This includes the user’s name, address, connection records (including session times and durations), the date the user began using services, the types of services used, the IP address or other instrument number, and payment information (including credit card and bank account numbers).

The next type of legal process, slightly more difficult to obtain, is a 2703(d) order, called that because it is described in section 2703(d) of the SCA. A “d order” is a court order, meaning that unlike a subpoena it requires a law enforcement agent to go before a court and show that there are “specific and articulable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe” that the requested data is “relevant and material to an on-going criminal investigation.”[114] The d order allows law enforcement to collect non-content information, which includes data such as e-mail headers, recipient e-mail addresses, and any other account logs that the provider may maintain.

As described above, both subpoenas and d orders can be used to get data other than content. However, the data that law enforcement is most likely to be interested in would be classified as “content,” and includes things such as e-mail subject lines, e-mail content, and instant message text. Under the letter of the law, both subpoenas and d orders may be used in certain limited circumstances to also get content information. For instance, the law allows law enforcement to obtain opened e-mails or other stored files, or unopened e-mail in storage for more than 180 days, using just a subpoena or a d order, as long as law enforcement provides notice to the user.[115]

Although the text of the law enables law enforcement to obtain content information, in limited circumstances, with only a d order or a subpoena, in actuality, law enforcement generally needs to use a third type of process to get content information: a warrant. Despite the text of the SCA, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, with jurisdiction over the states of Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee, held in United States v. Warshak that the government needs a warrant to obtain e-mail content.[116] Although that holding is technically limited to the geographic region of the 6th Circuit, almost all the major Internet companies rely upon the Warshak decision to require a warrant before providing any content information, despite the fact that such a conclusion is seemingly inconsistent with the SCA itself.[117]

Because a search warrant allows for the collection of content, and is therefore more invasive than subpoenas and d orders, it is also harder to obtain. To obtain a warrant, a law enforcement agent must demonstrate to a court that there is “probable cause” that information related to a crime is in the specific place to be searched. In addition to content information, warrants can obtain all the non-content data that a d order and subpoena can collect (and a d order can collect all the subscriber information that a subpoena can collect).

For terrorism or national security related investigations, the government has three additional levers for the collection of data from online intermediaries. National Security Letters (NSLs) allow the FBI to obtain telephone and e-mail records (and associated billing records), “relevant to an authorized investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities,” but not the content of the messages themselves.[118] Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act amended FISA to enable secret court orders, approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), to require third parties, such as ISPs or telephone providers, to provide business records deemed relevant to terrorism or intelligence investigations. The government used the Section 215 authority, for example, to compel Verizon to provide all cell phone metadata.[119] The third lever is Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act, which allows the government to collect both the content and non-content information of targeted non-U.S. persons reasonably believed to be outside of the United States.

Subpoenas, d orders, warrants, 215, and 702 orders represent just some of the wide array of legal tools at the disposal of American law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Additional tools include wiretaps and pen-registers, which enable law enforcement to obtain prospective, instead of retrospective, data. With this array of tools and the treasure trove of personal information that online intermediaries may store, it means that once intermediaries reach a sufficiently large size, it is only a matter of time before law enforcement or intelligence agencies will serve legal process.

[114] 18 U.S.C. § 2703(d).

[115] See 18 U.S.C. § 2703(a), (b).

[116] See 631 F.3d 266 (6th Cir. 2010).

[117] See, e.g., Twitter Transparency Report at <https://transparency.twitter.com/country/us> (“A properly executed warrant is required for the disclosure of the contents of communications (e.g., Tweets, DMs).”).

[118] 18 U.S.C. § 2709(b)(2).

[119] Full text of Section 215 Order the government served on Verizon. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/jun/06/verizon-telephone-data-court-order>

III. Case Studies

A. Sex Trafficking in Online Classified Advertising – Craigslist.org and Backpage.com

1. Introduction

As discussed in the Legal Landscape Primer of this report, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act enables a wide array of online intermediaries to operate within the United States without the burdens of either monitoring user-generated content or (except in the case of certain intellectual property claims) implementing a system for removal for such content.

While this has facilitated the creation of many platforms for user-generated content, Section 230’s protections are controversial. Many believe that the rule protects what is worst about the Internet and social media rather than what is best about it. Plaintiffs who legitimately claim to be harmed, as well as law enforcement officials attempting to protect the public, are often frustrated by their inability to stem unlawful online content at the obvious source, the intermediary. This frustration is particularly acute when the websites that provide access to such content seem to revel in (and profit from) their users posting content that is tawdry or mean-spirited, or even illegal under state laws.

This case study examines a six-year effort by officials of state (rather than federal) government to hold intermediaries accountable for a specific activity: namely, the hosting of online advertisements alleged to facilitate prostitution and sex trafficking. A recurring theme throughout this case study is the barrier that Section 230 poses to efforts by state governments to shut down these advertisements, and the ways that these governments have attempted to circumvent Section 230 through public pressure, judicial action, and legislation.

This case study focuses on two websites in particular, Craigslist and Backpage.com:

- Craigslist is a classified advertisements service that has been available via the Internet since 1996, and currently the largest such online service in the United States. Craigslist hosts separate sub-domains for separate geographic regions; more than 700 regions in seventy countries currently have Craigslist sites, with content available in multiple languages. Listings on the site include advertisements and solicitations for jobs, housing, the sale of personal items, and various services. The listings for services originally included a section for “erotic services.” Craigslist’s terms of service expressly prohibit the use of the site to advertise illegal activities.

- Backpage.com, launched in 2004, is the second largest online classified advertisements service in the United States after Craigslist. Like Craigslist, it offers listings for a wide range of proposed transactions and is available in multiple countries and languages. Backpage.com was originally owned by Village Voice Media. The site contains a section for “adult entertainment services,” but, like Craigslist, prohibits the use of the site to advertise illegal activities.

2. “Erotic” and “Adult” Advertisements on Craigslist – Negotiation Leads to Concession

As a general classified advertising service, Craigslist had hosted a section of “erotic services” content on its service, created by its users and over which Craigslist could plausibly claim immunity for intermediary liability under Section 230. While Craigslist’s protection under Section 230 was never pierced and adult content had been on the site for years, a series of events taking place from March 2008 to September 2010 lead to the rapid shutdown of these listings on the site.