Intermediary Liability – Not Just Backward but Going Back

This paper provides an analysis of the Korean “Act Regarding Promotion of Use of Information Communication Networks and Protection of Information” that governs intermediary liability in Korea for defamatory or otherwise rights-infringing contents. This paper asserts Article 44, 2, which should have created protection from liability like other intermediary liability regimes around the world, has instead become an affirmative way to impose intermediary liability.

Intermediary Liability - Not Just Backward but Going Back

Author: Kyung-Sin (K.S.) Park

Korea University Law School

Abstract: This paper provides an analysis of the Korean “Act Regarding Promotion of Use of Information Communication Networks and Protection of Information” that governs intermediary liability in Korea for defamatory or otherwise rights infringing content. This study makes the case that the Act’s Article 44, 2, which should have created protection from liability like other intermediary liability regimes around the world, has become instead a way to impose intermediary liability in Korea. The paper also gives an overview of relevant court cases, the latest (2009) of which, in author’s analysis, has had a “crushing” effect on protections from liability because it imposed liability for content that the intermediary was not aware of and was not given any notice of. This supports the argument that Article 44, 2 is unconstitutional because it imposes on intermediaries a de jure or de facto obligation to take down lawful content. Citing statistics on compliance with take down requests by the three major intermediaries in the country, the author observes that as a result of such liability-imposing regime the sheer volume of censorship has become problematic, and that politicians use requests to take down legal content that is critical of their policy decisions. This case also illustrates how intermediary liability rules that might seem benign are not necessarily so. To preserve the future of the Internet, rules that hold intermediaries responsible for removing unlawful content should be carefully considered before they are implemented. This case illustrates how Korea is a country where the special characteristics of the Internet are only considered for the sake of suffocating the power of the Internet.

[1] The author has adapted significant portions of his argument from, “Unconstitutionality of Korea`s Temporary Blinds on Internet -"Thou Shall Not Speak for 30 days What Others Do Not Like", Joongang Law Review, Vol.11 No.3 Pages 7-51 [2009] http://m.riss.kr/search/detail/DetailView.do?p_mat_type=1a0202e37d52c72d&control_no=446c374bd83dd689ffe0bdc3ef48d419.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Landscape of Korean intermediaries

A. Market Survey

B. Social Significance of Different Intermediaries

C. State Paternalism

D. Foreign Companies

III. Korea’s Intermediary Liability Regime

A. Intermediary Liability In General

B. Korean Law: Liability-Exemption or Liability-Imposition?

C. On-Demand Takedown Obligations

D. Intermediary Liability in Court

IV. Result: Private Censorship

V. People’s Response: Constitutional Challenge

VI. Conclusion and Impact Assessment

I. Introduction

This paper surveys South Korea’s landscape for intermediaries, and analyzes the regulations thereon and their impact on society in general in response to the Network of Center’s Guiding Questions on the Online Intermediaries research project. The author provides an overview of the country in section 2; discusses Korea’s intermediary liability regime in section 3; presents their impact on the industry and society in section 4; follows how law and industry have dynamically interacted in section 5; and finally concludes with suggestions for the future.

II. Landscape for Korean Intermediaries

A. Market Survey

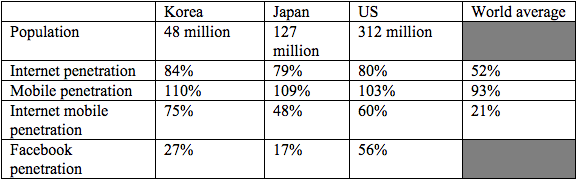

As of 2013, Korea had a total population of about 48 million people (83% urban) with an Internet penetration rate of 84%, mobile penetration rate of 110%, mobile Internet penetration rate of 75%, and Facebook penetration of 27%.[2] See below for comparison to Japan, U.S., and the world average.

Figure 1. Comparison of Internet use statistics.

Korea’s major intermediaries in each are as follows:

- Search engines: Naver, the local portal, has maintained 73% market share. Daum, the second largest local portal has roughly 21%, with GOOGLE covering the small remainder 3% (December 2012).[3]

- Micro-blogging: Twitter almost monopolizes the market, but if you include non-micro blogging, Naver still covers 80% of domestic bloggers.[4] In 2007, Naver already topped user visits per month[5] and its dominance grew over time ever since.

- Social Media: 31.3% of all people use SNS (increase by 7.8% in 2013, fast-growing). Kakao Story[6] accounts for 55.4% of users, Facebook for 23.4%, Twitter for 13.1%, and Cyworld[7] (SK Communications) for 5.5% as of January 2014.[8] However, it is the author’s opinion that Kakao Story numbers are exaggerated by the users who were given the Story accounts by default due to their membership with Kakao Talk, the dominant private messaging service, which not really a social “networking” service. Weighing the time spent using the services, it seems to this author that Facebook is by far the most widely used social networking service in Korea. This is quite a change since 2010 when Cyworld accounted for 50% of social media users.[9] Leaving out the messaging services, the rankings are as follows:

- South Korea SNS 2014: Own an Account (Monthly Active User)

- Any SNS 84% (48%)

- Facebook 75% (36%)

- Twitter 56% (22%)

- Google+ 38% (7%)

- Me2Day 33% (7%)[10]

- South Korea SNS 2014: Own an Account (Monthly Active User)

- Private messaging: Kakao Talk almost monopolizes the market.[11]

- User Created Content: YouTube has 75% but only in video contents.[12]

- Platform: Google Play 75.2%, due to the dominance of Samsung (100% Android) in phone markets (Apple 17.9%, Blackberry and Windows each 4%).[13]

As part of the overall Internet economy, the mobile Internet is most often used for search (96.8%), then for SNS (50.4%), shopping (36.4%), banking (33.1%), etc. Time-weighted, it is used most for chatting (81.2%), phone calls (visual incl, 69.7%), texting (69.%), and searches (42.8%).[14]

As expected, the top uses of mobile Internet are not typical revenue-generators. Below are the revenues of top 10 Internet companies in Korea:

- Top 10 Internet companies (by revenue)

- Naver (2.3 billion USD)

- Nexon (1.6 B USD)

- NCSoft (750 million USD)

- NHN Entertainment (640 M USD)

- eBay(640 M USD)

- Daum (530 M USD)

- Net Marle (497 M USD)

- Neo Wiz (443 M USD)

- Smilegate (360 M USD)

- Wemade (227 M USD)[15]

Notice, out of 10 companies, the majority are game companies. Only Naver and Daum are portals. Facebook, Twitter (SNS), Kakao are not major revenue-generators. Google Play revenues are not significant, either.

[2] We Are Social Singapore, “Global Digital Statistics 2014”, January 2014 http://www.slideshare.net/wearesocialsg/social-digital-mobile-around-the-world-january-2014, page 146-146 (cited sources: ITU, Facebook, U.S. Census Bureau, Global Webindex).

[3] Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning and Korea Internet & Security Agency, 2013 Korea Internet White Paper, http://isis.kisa.or.kr/mobile/ebook2/2013/download/service.pdf, p. 180.

[4] There does not seem to be statistics tracking blogging or micro-blogging separately. “80%” is usually tossed around by Internet pundits who seem to derive that number from the search engine market share for the reason that bloggers are likely to expect search engines to promote the blogs on their own services and therefore likely to use the blog platform affiliated with the most popular search engine Naver.

[5] Nielson Korean Click Co., Ltd., “Domestic Blogging Services: Growth and Change”, November 14, 2007 http://www.koreanclick.com/information/info_data_view.php?id=189.

[6] An Instagram-like SNS launched by Kakao Talk, the dominant private messaging service, opened.

[7] A My Space-like service launched by the SK conglomerate. This remains the only non-telco intermediary founded by Korean chaebols.

[8] Korea Information Society Development Institute, KISDI Stat Report “SNS Usage Analysis” (2013.12.26) http://www.kisdi.re.kr/kisdi/fp/kr/publication/selectResearch.do?cmd=fpSelectResearch&curPage=1&sMenuType=3&controlNoSer=43&controlNo=13270&langdiv=1&searchKey=TITLE&searchValue=sns&sSDate=&sEDate=.

[9] Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, http://m.korea.kr/newsWeb/ml/policyView.do?newsDataId=148703840&currPage=61.

[10] We Are Social Singapore, infra., p. 148.

[11] Newsis, “Kakao Talk’s Market Share at 92%. . Bandwagon Effects in Mobile Messenger Service, Twice That of Mobile Telecom”, September 23, 2014, http://www.newsis.com/ar_detail/view.html?ar_id=NISX20140923_0013187317&cID=10402&pID=10400.

[12] Newsis, “YouTube, Clearing the Video Market Thanks to Mandatory Identification Rule”, October 9, 2013, http://www.newsis.com/ar_detail/view.html?ar_id=NISX20131009_0012419136&cID=10301&pID=10300.

[13] 2013 Korea Internet White Paper, infra, p. 29, http://isis.kisa.or.kr/ebook/WhitePaper2013.pdf.

[14] Korea Internet and Security Agency, “Year 2013 Mobile Internet Usage Survey”, January 15, 2014. http://isis.kisa.or.kr/board/index.jsp?pageId=040000&bbsId=7&itemId=801&pageIndex=1.

[15] Blog ‘Under the Radar’, “2013 Internet Industry, Top 10 Revenue Generators”, March 7, 2014, http://undertheradar.co.kr/2014/03/07/114-2013-%EC%9D%B8%ED%84%B0%EB%84%B7%EC%97%85%EA%B3%84-%EB%A7%A4%EC%B6%9C-top10/.

B. Social Significance of Different Intermediaries

In non-economic terms, certain intermediaries are more relevant than others – e.g. in terms of market share, popularity, usage patterns, and their impact on society. Naver and Daum curate and present other agencies’ news in their own pages, host original user-created discussion pages, blogs (Naver), and cafe pages (Daum), which have become major platforms for political debates. Facebook has become the socializing platform of choice for both conservative and progressive circles. Twitter, which had become the main battleground for political discussions even prior to 2012, has become even more famous as it was revealed that National Intelligence Services – the country’s intelligence agency – had conducted major public-opinion-manipulation campaigns using Twitter before and during the Presidential election in 2012.[16]

In late 2014, the Korean intermediary Kakao Talk, the dominant messenger service provider, became the center of public attention when the Prosecutors’ Office announced a new campaign to track down and indict the postings “causing division in national unity and skepticism of the government” for criminal defamation, and in doing so, mentioned Kakao Talk as a possible target for such search and seizure. This shocked the entire nation, 90% of who use Kakao Talk, because it has been a private messenger service connecting only those who knew each other. As a result, many ‘migrated’ to a foreign service, Telegram, whose server is located overseas, apparently safe from Korean authorities’ search and seizure.[17]

[16] New York Times, “Prosecutors Detail Attempt to Sway South Koran Election”, November 21, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/22/world/asia/prosecutors-detail-bid-to-sway-south-korean-election.html?_r=0.

[17] BBC “Why South Koreans are Fleeing the Country’s Biggest Social Network”, October 10, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-29555331.

C. State Paternalism

Indeed, one significant factor affecting online intermediaries is state paternalism, which pervades the country’s industrial institutions and practices. For instance, all Internet companies with capital larger than about USD 100K are required to register and are given a “value-added telecommunication business” number, which can be taken away if they do not operate in compliance with the government’s laws and regulations or if their operation “significantly hurts consumers’ interests”.[18] This environment creates a cloud under which the domestic companies feel the pressure to comply with even extra-legal guidance of the government. For instance, as you will read below, the “temporary take-down” regulation can be read as optional but effectively works as if it is mandatory, as do several other “optional” regulations, like the Korea Communication Standards Commission’s “correction requests (to take down contents)”[19] and warrantless subscriber data requests. The compliance rates of these regulations were near 100% until a huge judgment came down on the latter in October 2012 in a consumer lawsuit filed by PSPD Law Center.[20]

[18] Article 27 Paragraph 2 of the Telecommunications Business Act.

[19] See K.S. Park, “Administrative Censorship on Internet in Korea”, http://opennetkorea.org/en/wp/administrative-censorship.

[20] See K.S. Park, “Internet Surveillance in Korea 2014”, http://opennetkorea.org/en/wp/main-privacy/Internet-surveillance-korea-2014 I myself had the fortune of initiating and directing the legal campaign for the lawsuit, which is now pending in the Supreme Court.

D. Foreign Companies

The regulations, hard and soft, apply equally to Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Microsoft, which all have local offices but whose servers are located overseas, exempting the owners from local income tax liabilities. The extraterritoriality of the servers has also provided a rationalization for the fact that the government has not applied various intermediary regulations to these overseas providers, creating what domestic competitors decry as “reverse-discrimination.”[21] The most infamous domestic-only regulation was a mandatory identity verification rule, which was snubbed only by overseas providers before it was struck down in 2012 in a constitutional challenge filed by PSPD Law Center.[22]

[21] Business Korea, “Korean ICT Companies Suffering from Reverse Discrimination due to Governmental Regulations”, http://www.businesskorea.co.kr/article/2274/%E2%80%9Creverse-discrimination%E2%80%9D-korean-ict-companies-suffering-reverse-discrimination-due.

[22] Constitutional Court's Decision 2010 Hunma 47, 252 (consolidated) announced August 28, 2012. K.S. Park, “Korean Internet Identity Verification Rule Struck Down” http://m.blog.naver.com/kyungsinpark/110145810944.

III. Korea’s Intermediary Liability Regime

A. Intermediary Liability In General

What defines the Internet? The defining feature of the Internet is its structure as an extremely distributed communication platform, so distributed that it allows almost all individuals to participate in mass scale communication. All individuals are allowed to post individual views and opinions without anyone’s approval, and all individuals are allowed to view and download all other individuals’ postings.

How some people react to questionable material found online shows how they have not accustomed themselves to this freedom of the Internet. They think that Internet companies should be responsible for the content on their services. It is true that illegal activities such as defamation and copyright infringement that abuse the power of the Internet should be combated. However, unless society wants to paralyze the freedom of unapproved uploading and viewing and therefore the power of the Internet – an intermediary should not be expected to know who posts what content and should not be held responsible for defamation or copyright infringements committed by content on its services. If intermediaries are held liable for this content, the intermediaries will have to protect themselves by constantly monitoring what gets posted on their services. If this happens, when a posting remains online it will appear to do so with the tacit consent of the intermediary in question. The power of the Internet – the freedom to post and download unapproved – will be dead.

For the same reason, no country imposes – for instance – content liability on broadband providers.[23] No common carrier would be in business if it were held liable for all the criminal conspiracies and deals taking place over its network. The same reasoning should be extended to the providers of web applications that greatly facilitate the exchange of ideas and contents, i.e. “portals” and “search engines.” The only difference with the common carriers is that the Internet companies carry the unlawful content on their servers, while the telecoms serve the contents en route. While some will surely abuse the free space created by these intermediaries, holding intermediaries liable merely for creating this space would be too threatening to the future of the Internet. Along this line of thought, on non-copyright-related matters the U.S. went further by claiming that no “interactive computer service” shall be considered a speaker or a publisher of such content.[24]

However, in other areas, many believe that there must be a limit on the exemption that intermediaries enjoy: the intermediary should not be immunized for the infringing content that it is aware, of or is given notice of and yet refuses to remove. Yet this idea of a limited liability regime is not satisfactory because intermediaries always face a stronger incentive to take down content than to keep it up. The reason for this is that, first, intermediaries are massive content processors whose interest in individual pieces of content is small and, secondly, tort liability regimes around the world are usually such that the legal implications for keeping a posting up (a malfeasance) is always greater than the legal implications for removing it (a nonfeasance).

Therefore, many countries have decided to set up “safe-harbor” regimes where intermediaries are exempt from liability if they follow certain clearly defined procedures aimed at unlawful content. The most widely popular of such regimes is the notice-and-takedown regime,[25] whereby an intermediary is given an exemption from liability as long as it removes content when it is it is given notice of the content’s infringing nature by the rights holder. Importantly, the notice-and-takedown safe harbor is not applicable to illegal content that the intermediaries have actual knowledge of before and/or without a notice provided by a rights holder or another person.

[23] Section 512 (a) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

[24] Communications Decency Act of 1996: 47 USC 230 “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

[25] DMCA section 512 (c) and (g).*

B. Korean Law: Liability-Exemption or Liability-Imposition?

In Korea, the idea that the intermediaries must be given exemption from liability in the way of safe harbors appears to have been misinterpreted: what Korea has is not an intermediary liability exemption regime but intermediary liability imposition regime. The relevant provisions of the ‘Act Regarding Promotion of Use of Information Communication Networks and Protection of Information, Article 44-2 (Request to Delete Information)’ are as follows:

- Paragraph 1. Anyone whose rights have been violated through invasion of privacy, defamation, etc., by information offered for disclosure to the general public through an information communication network may request the information communication service provider handling that information to delete the information or publish a rebuttal thereto by certifying the fact of the violations.

- Paragraph 2. The information communication service provider, upon receiving the request set forth in Section 1 shall immediately delete or temporarily blind, or take other necessary measures on the information and immediately inform the author of the information and the applicant for deleting that information. The service provider shall inform the users of the fact of having taken the necessary measures by posting on the related bulletin board.

- Paragraph 4. In spite of the request set forth in Section 1, if the service provider finds it difficult to decide whether the rights have been violated or anticipates a dispute among the interested parties, the service provider may take a measure temporarily blocking access to the information (“temporary measure”, hereinafter), which may last up to 30 days

- Paragraph 6. The service provider may reduce or be exempted from liability by taking necessary actions set forth in Paragraph 2.

As is immediately apparent, the provision is structured not with such phrases as “the service provider shall not be liable when it removes . . .” but starts out with a phrase “the service provider shall remove …” Paragraph 6, referring to the “exemption from or reduction of liability in event of compliance with the aforesaid duties,” makes a feeble attempt to turn the provisions into an exemption provision like the notice-and-takedown of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. However, the exemption here is not mandatory, but is dependent on the Courts because the law states that the intermediary “may be reduced or exempted,” rather than “shall be exempted.” In fact, none of the service providers interpret Article 44-2 as an exemption provision that they are allowed to deviate from on the simple penalty of foregoing a safe-harbor. All of them interpret it as an obligatory provision that they must comply with.

Indeed, historically, the predecessors of Article 44-2 (Article 44 Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Network Act enacted 2001.7.16, Law No. 6360)[26] simply required the service provider to take down content upon the request of a party injured by that content and did not provide any exemption. Article 44 began as a simple idea that the service provider shall at least be responsible for content that is infringing if someone had complained about that content previously. Then, many service providers complained that they were not capable of determining whether certain content was infringing or not. In response, the law was amended in 2007 (Enacted 2007.7.27 Law No. 8289) into Article 44-2 to create a “temporary (blind) measure” for “border-line” content, so the service provider can now fulfill their responsibility under the previous law.[27] Together with that amendment, the noncommittal reference to possible “reduction or exemption” found its way into the law. The central idea that remained in each version was that the intermediary must remove infringing content upon demand.

The general idea of holding the intermediaries liable for identified infringing content seems innocuous, but the Korean case compellingly illustrates below why this should be abandoned.

[26] http://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=0&subMenu=2&query=%EC%A0%95%EB%B3%B4%ED%86%B5%EC%8B%A0%EB%A7%9D#liBgcolor31.

[27] http://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=0&subMenu=2&query=%EC%A0%95%EB%B3%B4%ED%86%B5%EC%8B%A0%EB%A7%9D#liBgcolor20.

C. On-Demand Takedown Obligations

As explained below, Article 44-2 Paragraphs 1, 2 and 4 of the Act Regarding Promotion of Use of Information Communication Network and Protection of Information ("Network Act") states that service providers are required to take at least a "temporary measure" on all content upon which a takedown request has been made, regardless of the legality of the content.

The first possible interpretation is that the statute sets up such on-demand takedown obligations explicitly. Although it speaks of an obligation to remove only when someone “whose rights have been violated” makes such request, it is impossible to know ex ante whether a rights infringement has taken place. So the only feasible interpretation is that such obligation arises whenever someone thinks and proposes that his/her rights have been violated. Going further on this line of interpretation, this obligation can be filled by “temporary measure,” but this the minimum: the intermediary must take some abatement action. Now, the statute thus interpreted is in conflict with all known constitutions and international human rights treaties which allow freedom of speech to be violated only in favor of other protected rights or values.

Another more generous interpretation is possible: As you can immediately see from Paragraph 1 and 2, if someone complains of their infringed rights, the provider must take down the content if it is infringing. Now, there will be no problem if the takedown obligation applies only to that content that actually injures others. Indeed, Paragraph 1 limits its application only to “anyone whose rights have been violated.” However, even if this is the case, the service providers will have a strong incentive to remove the content regardless, because otherwise the provider must risk being found in the wrong by courts and therefore being liable as a contributor to the dissemination of the infringing content. Usually, the service providers retain editorial control over the content through their Terms of Service so that they will not be held liable by the authors of the content for removing the content. Article 44-3 of the Network Act even codifies this rule.[28] On balance, the service provider always has a stronger incentive to take down content than to keep it up.

Now, Paragraph 4 states, in paraphrase, “the service provider may take a temporary measure (instead of permanent removal) if it is difficult to know whether the contents are infringing or when a dispute is expected between the parties.” This should mean that, even if the content is later found to be infringing, the service provider will not be held liable for the content if it has taken a temporary measure. While this seems to soften the de facto censorship effects of Paragraphs 1 and 2 by providing a less drastic alternative to a permanent removal, it does exactly the opposite. What is diabolical is that the permissive “may” in Paragraph 4 will encourage the intermediaries further to remove perfectly lawful content. This further aggravates the imbalance of incentives in favor of restricting content rather than keeping it up.

Make no mistake about it: under this second interpretation, the failure to take abatement action will result in liability only if the content is later found to be actually infringing. However, the intermediaries, not knowing for sure what content is infringing, will have strong incentives to take down even lawful content instead of risking being found liable later. Maybe a better expression of the dilemma is that the providers will be “chilled” into doing so, not because the concept “rights-infringing” is vague all the time, but because it is vague ex ante. On top of that, Paragraph 4 provides yet another incentive in favor of removing content by providing exemption from any liability for doing so.

Initially, the service providers were expected to gravitate away from permanent removals, for which there is no ex ante exemption, and toward temporary measures, for which there is ex ante exemption. This prediction turned out to be true. Naver, the number one content host, has often responded to all takedown requests with only temporary measures; Daum, the number two content host, eventually caught up in 2010.

In sum, contrary to the spirit of intermediary liability regimes around the world aimed at shielding the creators of online spaces from liability for what goes on in that space, Korean law ends up imposing de facto obligations on the intermediaries to censor lawful material, an obligation that did not exist before Article 44 or 44-2. The next section examines how courts dealt with intermediary liability before the current Article 44/44-2 regime.

[28] Article 44-3 The service provider may take a temporary measure voluntarily if it is recognized that the information circulated through the network operated and managed by the provider is infringing another’s rights.

D. Intermediary Liability in Court[29]

The Korean Supreme Court has ruled three times significantly on intermediary liability. In 2001, the Court held an electronic bulletin board provider liable for refusing, even upon demands both by the injury claimant and a government censorship body, to take down for a period of 5-6 months postings deprecating a pop singer’s fan. The Court ruled that the intermediary had “a duty to take adequate measures when it knew or had reason to know of a defamatory posting.”[30] This was a fairly typical case.

In 2003, when the Court was asked to find an intermediary liable for postings defaming a local politician, the Court took that as an opportunity to further limit when the duty to take adequate measures arises. [31] The Court held that, an intermediary, even if it knew or had reason to know of the defamatory material for 52 days, should not be held responsible unless a comprehensive analysis of the following factors point to such responsibility: the posting’s purpose, content, duration and method, the damages it has caused, the relationship between the speaker and the injury-claimant, the claimant’s attitude, including whether rebuttal or takedown was requested, the size and nature of the site posted, the degree of for-profit nature of the site, when the operator knew or could have known the posting’s content, and the technological and pecuniary difficulty in taking down, etc.[32] Having said so, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court decision that imposed liability for pre-takedown exposure. The Supreme Court’s rather terse ruling sounds very generous, refusing to impose liability even upon knowledge of some indiscretion, especially given that this was before the exemption provision was added to Article 44-2. However, the ruling stands on the narrow fact that the intermediary here did comply immediately with the takedown request. Some said it made sense to require knowledge of the illegal character of the content.[33]

Then in 2009, a crushing judgment[34] came out where the Korean Supreme Court issued a decision holding web portal sites Naver, Daum, SK Communications, and Yahoo Korea liable for the defamation of the plaintiff when user postings on those sites accused him of deserting a girlfriend upon her second pregnancy after he had he talked her into aborting the first, after which the girlfriend committed suicide. The court upheld judgments of 10 million won, 7 million won, 8 million won, and 5 million won, respectively, against these services.”

Specifically, the court held that (in paraphrase):

Barring special circumstances, the intermediary shall be liable for illegal content to the same extent as a news agency and therefore shall be liable when (1) the illegality of the content is clear; (2) the provider was aware of the content; and (3) it is technically and financially possible to control the contents. On top of the duty to take down such content immediately, the intermediary has a duty to block similar postings later on. The Court will find the provider’s requisite awareness under (2) above:

a) When the victim has requested specifically and individually for the takedown of the content; b) When, even without such request, the provider was concretely aware of how and why the content was posted OR c) When, even without request, it was apparently clear that the provider could have been aware of that content.

The end result is that the intermediary will be absolutely liable for a posting later found to be “clearly” defamatory if “it was apparently clear that the provider could have been aware of that content” even if the victim did not notify the intermediary of the existence of the content.

This sets up what is probably one of the most strict intermediary liability regimes because it imposes liability for situations where content is “unknown but could-have-[been]-known.” Anupam Chander plainly describes this ruling as stating that a web service “must delete slanderous posts or block searches of offending posts, even if not requested to do so by the victim.”[35] It is true that the intermediary may be held liable for the content that looks clearly illegal ex ante, but should this liability exist even when the intermediary did not know?

True, DMCA notice-and-takedown immunity[36] does not apply to content that OSP had “actual knowledge” of the infringing nature of, or “awareness of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent.” However, the DMCA is a safe harbor provision. It merely says that the safe harbor will not apply in case of “actual knowledge” or “awareness.” It does not say that the OSP will be held liable in cases of such knowledge or awareness.

Furthermore, there is a world of difference between possible awareness – encompassed by the phrase “could have been aware” in the Korean ruling – on one hand, and “actual knowledge” or “awareness” on the other. The intermediaries, when facing such a liability regime, will have strong incentives to monitor all the content in order to make sure that there are no unknown clearly defamatory postings that it “could have been aware” of, but that they did not remove. This sets up a general monitoring obligation that kills the power of the Internet. Indeed, the Court does state that “[if the three conditions are met], the intermediary has a duty to take down such contents immediately AND block similar postings later.”

What is more, this was not even a case interpreting the Article 44/44-2 regime because the cases here are concerned the intermediary’s role when the victim did not make a takedown request or before such a request was made. The Court was already ready to impose a publisher-like liability on the intermediary and a monitoring obligation.

[29] Woo Ji-Suk, “A Critical Analysis of the Practical Applicability and Implication of the

Korean Supreme Court Case on the ISP Liability of Defamation” LAW & TECHNOLOGY, Vol.5, No.4: pp78-98. July 2009 <http://plan2work.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/ebaa85ec9888ed9bbcec8690ec9790-eb8c80ed959c-ec9db8ed84b0eb84b7ec849cebb984ec8aa4eca09ceab3b5ec9e90isp-ecb185ec9e84-ec9ab0eca780ec8899.pdf>.

[30] Supreme Court, 2001.9.7 Judgment, 2001Da36801.

[31] Supreme Court 2003.6.27 Judgment, 2002Da72194.

[32] Supreme Court, 2003.6.27 Judgment, 2002Da72194.

[33] Hwang Sung-Gi, http://m.riss.kr/search/detail/DetailView.do?p_mat_type=1a0202e37d52c72d&control_no=12cb6a3625533040ffe0bdc3ef48d419.

[34] Please review a foreign scholar’s response to this ruling. Anupam Chander, “How Law Made Silicon Valley” EMORY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 63:639 (2014), http://www.law.emory.edu/fileadmin/journals/elj/63/63.3/Chander.pdf

[35] Supreme Court, 2008Da53812, Apr. 16, 2009 (S. Kor.).

[36] Section 512(c)(1)(A)(ii), 512(d)(1)(A).*

IV. Result: Private Censorship

In summary, Article 44-2 states that all content should be taken down upon demand even if lawful. The Supreme Court decisions state that all unlawful content should be taken down even if unknown to the intermediaries. Together, the Court decisions encourage private censorship by intermediaries. On top of the censorship system triggered by private notices, Korean law provides for the Korean Communication Standards Commission which issues “correction requests” to all intermediaries, including telecoms, to take down or block domestically the content the Commission finds to be illegal. What is significant for now is that these injunctive functions, together with monetary damages, anticipated by the above-described liability regime, will provide stronger incentives to the intermediaries to take a heavy-handed approach toward censorship.[37] We will now look at some numbers and cases for illustration.

We will not look at copyright-related takedown notices, which may make up more than 90% of takedown requests in other countries, because the Korean Copyright Act sets up a different liability scheme for copyright-related takedown requests. The Network Act’s liability scheme affects only takedown requests related to defamation, privacy, interference with business, etc. Although the Network Act’s liability scheme on its face covers copyright as well, the Copyright Act’s scheme takes precedence in copyright issues in accordance with the principle of generalia specialibus non derogant. Although there will be issues with copyright-related on-demand takedowns, the Copyright Act’s liability scheme was quite similar to the American DMCA and is now more so under the KORUS FTA-triggered amendment that closed the final loophole by making the liability exemption mandatory.

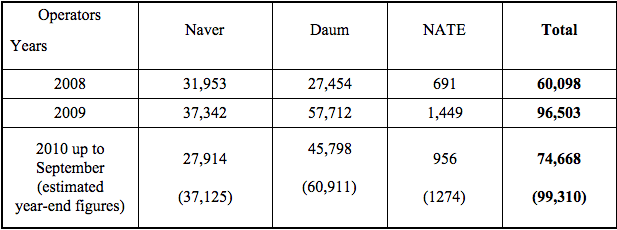

There is nothing similar to the Transparency Reports of U.S. OSP’s that are published by Korean intermediaries. There are only statistics occasionally obtained through private sources along with legislators who exercise their clout with agencies, which can in turn make various disclosure demands to the intermediaries licensed or registered with them. MP Choi Moon-Soon obtained the relevant data from the top three top content host intermediaries though the Korea Communications Commission and made the following disclosure in November 2010.[38]

Figure 2. Non-copyright related takedowns pursuant to Article 44-2

Figure 2. Non-copyright related takedowns pursuant to Article 44-2

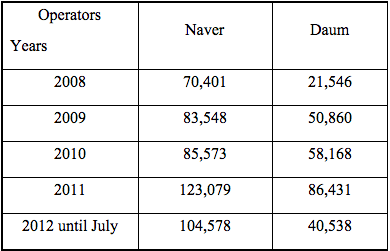

After learning that the number of takedowns executed by the top two content hosts exceeded that of other hosts greatly, MP Nam Kyung-pil obtained similar data on the two content hosts in October 2012,[39] shown below.

Figure 3. Non-copyright related takedowns pursuant to Article 44-2

Although the differences in the two tables need some explanations,[40] the following facts are uncontested:

- The number of URL takedowns privately requested under Article 44-2 of the Network Act for non-copyright purposes has increased over time.

- The annual number of URLs taken down by Naver hover above 100,000 and for Daum is about 50-70% of Navers’ number.

How serious is this? There is nothing here that we can compare to the situation in the U.S. because Section 230 of CDA insulates the intermediaries from liability for defamation and other non-copyright related laws. However, we can compare these Korean numbers to government-originating takedowns in other countries. Google received only about 4,000 takedown requests in 2012 from the whole world, only about half of which Google complied with.[41] So, 100,000 in Korea vs. 2,000 the whole world vis-à-vis Google! As another example, the Korean government’s censorship body – the Korean Communication Standards Commission – issued 54,385 takedown requests to various intermediaries in 2011, out of which only 668 were related to defamation and other rights infringement.[42] Although the number of URLs is usually greater than the number of requests – for each request may cover more than one URL – the rights-infringement category of KCSC activities usually covers less than 10 URLs. This means that private censorship takedowns through Article 44-2 is more than 10 times the number of rights-infringement takedowns executed by the Korean government.

It is not just the volume of censorship that is problematic. Politicians and government officials often make the takedown requests on postings critical of their policy decisions that are clearly lawful as illustrated below. Takedown requests were made for the following:

- A posting[43] critical of a Seoul City mayor’s ban on assemblies in the Seoul Square;

- A posting[44] critical of a legislator’s drinking habits and introducing his social media account;

- Clips of a television news report on the Seoul Police Chief’s brother who allegedly runs an illegal brothel-hotel;[45]

- A posting critical of politicians’ pejorative remarks on the recent deaths of squatters and police officers in a redevelopment dispute;[46]

- A posting calling for immunity from criminal prosecutions and civil damage suits on labor strikes;[47] and

- A posting by an opposition party legislator questioning a conservative media executive’s involvement in a sex exploitation scandal related to an actress and her suicide.[48]

[37] Park, Ahran. "Internet Service Provider’s Liability for Defamation: South Korea’s Balancing of Free Speech with Reputation" Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, The Denver Sheraton, Denver, CO, Aug 04, 2010.

[38] http://moonsoonc.tistory.com/attachment/cfile23.uf@133D7F0F4CE1EF660D3B87.hwp.

[39] http://www.ggetv.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=16781.

[40] Naver’s numbers in the first table represent the number of requests, which can cover more than one URL, while the Naver numbers in the second table represent the number of URLs taken down. Daum’s numbers in the first table include both permanent removals and temporary measures, i.e., blinds while Daum’s numbers in the second include only temporary measures. Daum’s numbers in the second table more and more came to represent the total number of takedowns as Daum cancelled its policy of undoing the blinds after 30 days, i.e., all temporary measures became permanent.

[41] https://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/government/.

[42] https://www.kocsc.or.kr/02_infoCenter/info_Communition_View.php?ko_board=info_Communition&ba_id=4909.

[43] http://blog.ohmynews.com/savenature/199381.

[44] The original posting now taken down is shown here. http://wnsgud313.tistory.com/156.

[45] http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/300688.html.

[46] http://blog.jinbo.net/gimche/?pid=668.

[47] http://blog.jinbo.net/gimche/?pid=492.

[48] http://bbs1.agora.media.daum.net/gaia/do/debate/read?bbsId=D115&articleId=610524.

V. People’s Response: Constitutional Challenge

It is okay not to institute intermediary immunity regimes such as the United States’ CDA Section 230 or DMCA Section 512 that shield intermediaries from liability for even unlawful content. However, Korea does much worse: it chills the intermediaries into taking down even lawful content as evidenced by the examples above. The PSPD Public Interest Law Center and others filed a constitutional challenge against Article 44-2 of the Network Act on the theory that the total result of the aforesaid provisions is that “Thou Shall Delay Saying What Others Dislike, As Long As 30 days.”[49] The Korean Constitution does not authorize suppressing speech that does not violate others' rights, the aforesaid provisions de facto require even lawful contents to be removed for up to 30 days therefore are unconstitutional.

Under the current statutory scheme, the temporary removal can be up to 30 days. Daum set it at the maximum of 30 days, while Naver set a period lasting until the publisher requests reposting. Naver's system looks a lot like a notice-and-takedown without mandatory exemption. However, the statute requires even Naver to take down content that is clearly lawful at least once. The rule "Thou Shall Not Say What Others Dislike Unless Thou Have Courage to Say Twice" is equally unconstitutional.

In 2012, the Constitutional Court rejected the challenges as follows:[50]

"The instant provisions are purported to prevent indiscriminate circulation of the information defaming or infringing privacy and other rights of another, and therefore have a legitimate purpose . . .Temporary blocking of the circulation or diffusion of the information that has the possibility of such infringement is an appropriate means to accomplish the purpose…

Freedom of speech requires absence of restriction in form, method, and timing of speech. Especially, in relation to publishing one’s opinions on a certain issue or event, the ‘temporal pertinence’ i.e. making a remark appropriate to the event in a time proximately related to the subject of that opinion is an important component of free speech and should be maximally guaranteed. This is an important function of freedom of speech that calls for self-correction through rebuttal and discussions about that speech, conducted at ‘the marketplace of ideas.’ Therefore, the instant provisions’ ‘temporary measure’ depriving the speech of the temporal pertinence by blocking access through information communication network presents a grave restriction on free speech…

However, . . .when another’s personal rights such as privacy or reputation are infringed or are anticipated to be infringed, a need to temporarily block the infringing information is greater than the need to guarantee the temporal pertinence of the information. The fact that the content was disclosed may be further propagated through other means, and may cause privacy-infringement and defamation to an equal extent. In such situation, publishing a rebuttal by the infringement complainant, blocking of the links, search restrictions, expeditious dispute resolution, etc., cannot be effective alternatives to accomplish the legislative purpose…

When a temporary measure is taken for the reason that “it is difficult to judge whether the rights have been infringed or when a dispute between the interested parties is anticipated”, the degree of restriction on the poster’s freedom of speech becomes greater. . . .However, in this situation, such measure has the effect of preventing frivolous improvised attacks or the spreading of information that as a result infringe on another’s rights in anonymous cyberspace . . ."

What was encouraging was that the Constitutional Court saw through to the practical effects of the provisions and recognized that the provisions are in fact tantamount to requiring the takedown of content that is not illegal. The Court itself states: “if the prerequisites are met, the service provider must without hesitation take the temporary measure.”

However, the opinion takes a curious turn and rationalizes the blocking of content on the basis of the mere “anticipation” of infringement. That speech can be banned on the basis of a possible illegality is a far departure from the established rules of free speech, such as a clear and present doctrine, void-for-vagueness, prior restraint ban, etc. The reason for such leniency is found in the earlier portions of the decision emphasizing how fast, far, and wide defamatory information travels through the Internet. However, the decision does not mention how fast, far, and wide corrective information can travel. Sure, the Internet’s self-corrective nature cannot be the basis for exempting all unlawful activities on the Internet. However, communicative efficiency of a medium cannot be a justification for taking down content that is lawful on that medium.

In all other types of media, only proven illegality can form the basis of liability, intermediary or primary. The Korean intermediary liability regime will impose liability for only provisional illegality if it takes place on the Internet. This constitutes discrimination against the Internet as a medium. It is not a frivolous question how humanity should deal with the special characteristics of the Internet, which calls for more research.

[49] Park Kyung-sin, “Unconstitutionality of Korea's Temporary Blinds on Internet - "Thou Shall Not Speak for 30 days What Others Do Not Like", Chung-Ang-Bub-Hak (Korean) <http://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001387276>

[50] Constitutional Court 2012.5.31 Decision 2010 Hun-ma 88.

VI. Conclusion and Impact Assessment

The Korean liability regime starts out with an innocent-sounding rule that an intermediary shall remove any user-created content infringing on the rights of another. The regime adds yet another innocent-sounding rule that an intermediary is free to remove a UCC temporarily as long as the intermediary anticipates a dispute or faces difficulty in deciding on the lawfulness. Such a regime, exempting not posting but only the removal of a post, has caused in Korea rampant private censorship, and the removal a significant amount of content duly informative to the public on civic affairs. The courts have not behaved better, imposing liabilities on the intermediaries for not taking down unknown content for which a takedown request did not even exist. Civil society has responded with a constitutional challenge, which ended with a surprising decision by the Constitutional Court that the Internet, due to its hyper-efficient mediating power, must be discriminated against so that even lawful content is subject to temporary removal if there are people who allege an injury.