Online Intermediary Liability in Thailand

This paper discusses the instability of the Thai government and society, and how this affects the implementation and creation of laws and policies relevant to Internet intermediaries. The paper discusses related laws and cases, along with primary survey data from Internet intermediaries.

Internet Intermediary Liability in Thailand

Author: Pirongrong Ramasoota

Thai Media Policy Centre, Faculty of Communication Arts,

Chulalongkorn University

Abstract: This paper discusses the instability of the Thai government and society, and how this affects the implementation and creation of laws and policies relevant to Internet intermediaries. The paper discusses related laws and cases, along with primary survey data from Internet intermediaries. The 7-year-old computer crime law, the centerpiece of intermediary liability provisions, does not make the distinction between different types of intermediaries – those that deal directly with content as opposed to those that are merely conduits for content. Additionally, while only one case has been prosecuted so far in association with the controversial lèse majesté law, there has been a visible chilling effect on Internet operators as a result of this law, substantiated by primary research. Although most surveyed intermediaries tend to accept the burden imposed by the provision, some members of this group – together with online activists – are mobilizing in support of an amendment to the computer crime law, particularly with respect to the differentiation of types of intermediaries, the proportionality of penalties to the offence, and the tendency of government agencies to ask for “cooperation” from intermediaries in monitoring Internet content. Under the current interim government, which was installed under a military coup, intermediaries are compelled to carry out more censorship and surveillance, while passing on more regulatory constraints to users than ever before.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Background Context

A. Political Context

B. Social Development Related to Online Intermediaries

C. Regime of Internet Content Regulation

D. Internet Control in Pre- and Post-2014 Coup

III. Laws, Past Prosecution, and Recommendations for Change

A. Computer-Related Offences Act B.E. 2550 (2007)

B. National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)’s Announcements

C. Past Prosecution and Regulatory Measures on Internet Intermediaries

1. Chiranuch Premchaiporn and Prachatai case

D. Recommendation From Civil Society on Alleviating Impacts from Intermediary Liability

IV. Research on Local Intermediaries and Their Content Practices

A. Burdens Imposed on Intermediaries

B. Content Filtering Practices

C. Types of Content Filtered

D. Transparency and Accountability of Content Regulation Process

E. Impacts of Intermediary Liability Provisions

F. Recommendations for Change in Intermediary Liability Provisions

G. Impacts on Content Regulation After Announcement of Martial law and the July 2014 Coup

1. Network and Access Providers

2. Content Providers

V. Conclusion

I. Introduction

Online intermediary liability is an emerging area for Internet studies in general and challenging terrain for research in Thailand, a country beset by chronic political instability and a media policy process uniquely rooted in the country’s political and economic circumstances. To attempt to provide a comprehensive understanding of intermediary liability in such a setting, this paper will delve into the background context surrounding Internet intermediaries, review key intermediary liability provisions together with relevant legal experiences, and provide empirical data from a first-hand survey of how different groups of Internet intermediaries in Thailand are coping with the liability scheme, and the consequences thereof.

II. Background Context

This section explores the political context, social developments, regimes of Internet content regulation, and the nature of Internet control related to online intermediaries before and after the 2014 coup.

A. Political Context

Thailand is a country located in Southeast Asia, with a population of 67.44 million. Since 1932, the country has been governed by a constitutional monarchy. Democratic rule and general elections have been interspersed with military dictatorships and coups. The last coup, the sixteenth to date, was staged on May 22nd, 2014 by a military junta known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), following months of protests against the civilian government of the populist Pheu Thai Party due to allegations of corruption and attempts to pass an amnesty law[1] that would provide blanket protection for wrongdoers in past political conflicts.

Since November 2013, anti-government forces led by the so-called People Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC), composed of opposition politicians, urban elites, sympathizers of the palace, and conservative academics, as well as millions of supporters, mainly from Bangkok and the Southern provinces, have staged rallies at major thoroughfares in the capital city, seizing the Government House and paralyzing many government offices. Their demand was the reform of Thai politics by removing the influence of the so-called Thaksin regime. Thaksin Shinawatra[2] is a former Thai leader who was ousted in another coup in 2006. He is also the older brother of then Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, who led the Pheu Thai Party to an election’s victory in 2011 and had been running the country’s administration ever since.

After sustained protests, Yingluck dissolved parliament in December 2013 and called an election. However, opposition MPs from the Democrat Party, which formed the core of the PDRC, led mass movements to boycott the elections, which were eventually nullified by the Election Commission on grounds of inadequate participation. Nevertheless, the protesters, led by the PDRC, vowed to continue demonstrating, claiming that her brother, ousted leader Thaksin Shinawatra, controlled the Yingluck government and that Yingluck lacked legitimacy to rule due to many charges of corruption. As a result of the House dissolution, the Yingluck administration became a caretaker government.

Meanwhile, Yingluck and members of the Cabinet were investigated by an anti-graft body and faced trial for a policy discrepancy related to the controversial rice mortgage scheme and abuse of power. In early May 2014, the Constitutional Court ruled that Yingluck had acted illegally when she transferred her national security chief, and ordered her and nine other cabinet members to step down, resulting in the Commerce Minister being reinstated as acting Prime Minister and creating a political void. Many viewed the verdict as a judicial intervention.

Amidst this impasse, the Army chief stepped in to resolve the situation by organizing talks between different the conflicting factions. The talk ended in another deadlock, prompting the army chief, who later became leader of the NCPO, to announce a seizure of power. It merits observation that the coup was announced a few days after the enforcement of martial law to curb sporadic violence in the capital city. To many, the bloodless coup in May was welcomed and seen as inevitable to end the stalemate between the conflicting factions, as well as the rising violence that accompanied the political conflict in many rally venues. Notably, the political conflict in Thailand in the last decade was often dubbed as “color-coded politics” to describe the ideological clash between the yellow-shirts[3] and the red-shirts,[4] who represent two opposing poles in the contemporary political divide. Media – big and small, online and offline – have been used to propagate and widen this political polarization, sometimes resorting to hate speech.

After the coup, a series of coup notifications were released to the public, including about a dozen that put tight controls on communication, including online social media. Internet service operators were summoned to meet with the junta, who requested cooperation in reporting and dissemination of junta information, and barred these operators from instigating unrest and criticism of the junta and their work. There was also a brief period of inaccessibility to Facebook, which was suspected to be coup-related, although the NCPO denied any involvement.

[1] The final draft of the bill, passed by the House of Parliament at unusual hour (4 a.m.) on October 31, 2013, would have pardoned protesters involved in various incidents of political unrest since 2004, dismissed corruption convictions of powerful politicians and annulled the murder charges against past national leaders that might have been responsible for the deaths of protesters in anti-government rallies.

[2] Thaksin Shinawatra, founder of the deposed Thai Rak Thai (TRT) Party, was a famous telecommunications tycoon, having made his fortune from satellite and mobile phone concessions through his family business, Shin Corporation. Thaksin is also a popular political leader who led the longest democratic and civilian rule — six years — in contemporary Thai history. Thaksin’s popularity was largely attributed to populist policies that featured income redistribution, cheap health care, microcredit schemes, and many policy innovations in support of globalization and neoliberal economy. However, he is not well liked by a large number of urban or middle-class voters who are repulsed by his arrogance, authoritarian tendencies, and policy discrepancy that benefit only his cronies. He was also widely accused of disloyalty to the crown, an accusation that was largely used as a justification for the September 19, 2006 coup. Even after he was deposed, Thaksin continued to be an influential figure in Thai politics. He reportedly masterminded several revolts including the red-shirt protest in 2010 which led to a House dissolution under then Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and a violent clash with the armed forces that led to more than 90 in casualties, both military and civilian.

[3] The “yellow-shirts” is another name for the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), a mass movement preceding the September 2006 coup that ousted Thaksin from the premiership. The PAD spent much of 2008 protesting against two successive Thaksin-nominated governments that arose from the December 2007 election. The PAD’s 190-day protest in 2008 was marked by the seizure of the Government House and the Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok. In 2009, leaders of the PAD entered electoral politics by establishing the New Politics Party. One of the PAD’s leaders, Sonthi Limthongkul, is a media mogul who has been instrumental in using his media corporation particularly a satellite television station called ASTV as a main tool to galvanize mass movements in support of the PAD. After the 2017 coup in May, ASTV was banned from airing signals.

[4] The “red shirts” is the informal name for the United Front of Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), a major political organization in the post-coup period. Members of the UDD are known for wearing red clothes during anti-government protests. Established in 2006 as Democratic Alliance against Dictatorship (DAAD), the main objective of the red shirts then was to fight against its arch rival -- the PAD -- and to support the ousted former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Supporters of the UDD are not only rural grassroots people who benefited from Thaksin’s populist welfare policy, but also include the urban middle class who admire Thaksin’s business-oriented administrative policy and action, and those who disapproved of the status quo that formed the core of the yellow-shirts.

B. Social Development Related to Online Intermediaries

In terms of Internet statistics, there are 23.8 million Internet users in Thailand, representing 35% of the population.[5] Mobile telephone users are numbered at around 120 million, based on the number of SIM cards distributed.[6] Around 40% of mobile users access the Internet via their smart phones, which most use to view online social media like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.[7] Bangkok has been ranked as the capital city with the highest number of Facebook users in the world.[8] Meanwhile, “LINE,” a mobile chat app that was developed by Japan-based LINE Corporation, is also extremely popular in Thailand. The country has the most LINE users of any country outside of Japan, with 61.1% of social media users – about 18 million – said to be using the application.[9]

Online intermediaries play a critical role in social development in Thailand, particularly in the protracted political conflict that the country has been embroiled in since 2005. In the latest political crisis that has developed since October 2013, social media became a key online channel for people to keep abreast of the current political climate, as well as to mobilize resources in support, as well as in defiance of the protest movements.

During the seven month-long protest against the popular but polarizing government of Yingluck Shinawatra, online media usage across services like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LINE, and Pantip.com (a popular online discussion form) in Thailand was very dynamic. In the first month after the protest began, for instance, Twitter was found to be the most used social media channel for protesting the controversial draft amnesty bill – the catalyst of the lengthy protest – with over 800,000 messages sent in one peak day in November 2013.

[5] 2014 Asia-Pacific digital overview from http://wearesocial.sg/

[6] Survey of Thailand’s communications market 2012-2013, Center for Telecommunications Economy Data and Research, National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission.

[7] Info graphics of Thailand mobile users, 2013. See http://www.veedvil.com/news/thailand-mobile-in-review-q3-2013/

[8] http://www.socialbakers.com/facebook-statistics/thailand

[9] http://www.veedvil.com/news/thailand-mobile-in-review-q3-2013/

C. Regime of Internet Content Regulation

As for Internet regulation in Thailand, a number of entities are involved. The Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (MICT), established in 2002, is the central organization that implements the Computer-related Offences Act B.E. 2550 (2007), better known as the computer crime law, along with the Technological Crime Suppression Division (TCSD) of the Office of National Police. The National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) regulates licenses for Internet services and International Internet Gateways. Therefore, all Internet service providers report to the NBTC under licensing obligations, while also being subject to the MICT’s Internet content filtering scheme.

Apart from prosecuting offences under the computer crime law, the MICT has also conducted constant surveillance and censorship of online content through specially recruited cyber-scouts and URL blocking via ISPs. Since the arrival of the computer crime law in 2007, court orders to block Internet content have increased from two URLs in 2007 to over 74,000 in 2012.[10] Examples of content targeted for filtering include lèse majesté or defamation of the royal family, drug trafficking, gambling, and prostitution – which are not necessarily offences as stipulated in Section 14 of the computer crime law that addresses content offences.[11]

According to a report published by iLaw, an online rights-based NGO, most of the offences prosecuted under the computer crime law are content-related.[12] Since the law came into effect in 2007, both the number of cases prosecuted and the number of websites that have had access blocked have increased, which coincided with the looming political conflict and polarization that has characterized Thai society in recent years. Cases involving lèse majesté, which is a serious crime in Thailand, were also on the rise in both online and offline communications during this period.

[10] Suksri, Sawatree, et al., Situational Report on Control and Censorship of Online Media through

the Use of Laws and the Imposition of Thai State Policies (Bangkok: iLaw and Heinrich Böll Foundation Southeast

Asia, 2010).

[11] Section 14 of the law provides for imprisonment for up to five years and/or a fine of up to 100,000 baht (approximately US $3,000) for these content-related offences. These offences are referred to as “import into a computer system,” of the following: 1) false data in a manner likely to cause damage to a third party or the public; 2) false data in a manner likely to damage national security or to cause public panic; 3) data constituting an offence against national security under the Criminal Code; and 4) pornographic data that is publicly accessible. The dissemination or forwarding of computer data in the nature under 1), 2), 3), and 4) are also offences and subject to the same criminality.

[12] Suksri, Sawatree, et al., Situational Report on Control and Censorship of Online Media, p. 5.

D. Internet Control in Pre- and Post-2014 Coup

During the highly volatile period under the Yingluck administration, the TCSD was pro-active in policing websites and online social media. In one instance in August 2013, the TCSD reportedly attempted to probe the conversations and comments posted on the highly popular social-media application, ‘Line’, to see if they violated the law or threatened national security. This incident was preceded by the summoning of four suspects for allegedly breaching Section 14 of the computer crime law and Section 116 of the Criminal Code by posting messages via social media, saying they anticipated a coup and urged people to stock up on food and water. These statements, according to the TCSD chief, could put people in a state of panic, and those who "liked" or "shared" the messages could be considered violators of the law as well. An open letter of opposition from four professional media organizations and an online rights-based group met the TCSD’s action. Meanwhile, the National Human Rights Commission also issued a statement warning police to exercise their authority carefully and not violate people's fundamental rights and freedoms.[13]

Since the coup on May 22nd, 2014 that toppled the Yingluck government and ended the months-long political crisis, the surprisingly popular junta known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has taken steps to restrict the spread of anti-coup sentiment. First, an order known as the NCPO Announcement was released on the day of the coup that called on ISPs to monitor and deter the publication of online information that might incite unrest in the country.

Then, another order was launched that summoned all 105 local ISPs to meet with the junta-appointed Cyber Security Operation Center (CSOC), in addition to representatives from major online intermediary services in the country, including Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and LINE, to discuss “cooperation” on the issue. That meeting, however, did not materialize as the invited companies failed to show up. Another scheduled trip to Singapore of the CSOC staff to meet with Facebook, Google, and LINE was also called off after it was deemed unnecessary.

Notably, Facebook was the first social media platform to experience blocking on May 28th, when it was inaccessible for about one hour. The outage was initially blamed on technical issues at the country’s gateway, but an MICT spokesperson later said that the action was intended to stop the spread of anti-coup messages. A Norwegian telecom firm, Telenor, which owns majority shares in the country’s second largest GSM mobile phone provider, later confirmed this.

[13] http://www.nationmultimedia.com/politics/Police-seek-to-check-Line-posts-30212462.html

III. Laws, Past Prosecution, and Recommendations for Change

This section reviews relevant legislations and measures that contain provision(s) related to Internet intermediary liability; a case study on intermediary liability prosecution; and recommendations by a key civil society stakeholder on ways to alleviate the impacts from Internet Thailand’s intermediary liability scheme.

A. Computer-Related Offences Act B.E. 2550 (2007)

This law (better known as the computer crime law), the first of its kind in Thailand, was enacted in 2007 by the National Legislative Assembly (NLA), an interim legislature that was installed by the military junta in the aftermath of the 2006 military coup that toppled the civilian government of Thaksin Shinawatra. Although there had been many versions of the draft law before, its passage immediately after the coup was seen by many as a direct effort to curb online dissent that formed largely in cyberspace since the conventional media sector – print and broadcasting – was tightly controlled by the coup-leaders.

Apart from sections that address crimes to computer systems, such as hacking, viruses, and electronic sabotage, the law also has specific provisions that address content offences. Section 14 of the law provides for imprisonment for up to five years and/or a fine of up to 100,000 baht (approximately US $3,000) for these content-related offences. These offences are referred to as “import into a computer system,” of the following: 1) false data in a manner likely to cause damage to a third party or the public; 2) false data in a manner likely to damage national security or to cause public panic; 3) data constituting an offence against national security under the Criminal Code; and 4) pornographic data that is publicly accessible. The dissemination or forwarding of computer data under 1-4 are also offences and subject to the same criminality.[14]

Section 15 of the law is the centerpiece of the intermediary liability provision. It states that, “A service provider who intentionally supports or gives consent to the commission of the offences under section 14 to a computer system under his control shall be liable to the same criminality as the offender under section 14.”[15]

While the two sections in the law deal exclusively with content offences, they do not make any distinction between the different types of intermediaries – those that deal directly with content – online service providers – and those that are merely conduits for the content – network and access providers. In other words, all Internet intermediaries are subject to the same liability for offences they do not commit, but take place within the network or communication space provided by them.

In a related vein, critics have also attacked the lack of clarity in the definition and implementation of the law.[16] Usually a public law would entail the subsequent issuance of a ministerial order that would provide more detail about how the law may be enforced. For instance, a ministerial order on the computer crime law might spell out what constitutes false information, or what the categories of information are constitute causing harm to national security, or the reasonable period of time that an intermediary is provided to remove illegal content after having been given a notice before being considered negligent or giving consent to the offence. Unfortunately, such a ministerial order does not exist in this situation.

Since the law came into effect, a few tangible impacts can be observed: the legalization of Internet blocking, indirect regulation via intermediary providers, and self-censorship of online content providers. Based on primary research findings,[17] Internet intermediaries of all types have set up new measures to regulate content and, in the process, are passing regulatory constraints onto users. These measures include the following:

- Keeping a log file of Internet traffic, including users’ IP addresses, for 90 days;

- Identification and certification clearance requirements for users at institutional servers and for subscribers to online discussion forums;

- Installing filtering software at organizational servers to enable content filtering;

- Setting up a 24-hour monitoring system for online discussion forums; and

- Incorporation of provisions of the law into codes of ethics/practice and terms of services.

Although the law has only been enforced for a few years, it has come under heavy criticism largely by Internet providers and online activists, both locally and internationally. Local rights-based NGOs have been mobilizing for an amendment to the law but, with the chronic instability of Thai politics in recent years, this amendment has been pushed back. And in the current coup-controlled environment in which free expression is the exception rather than the rule, it is unlikely the amended version of the law, if it proceeds, will reflect a more liberal tone than the existing law.

[14] Translation of the Computer-Related Offenses Act, Vol. 124, Section 27 KOR, Royal Gazette. 18 June 2007, p. 7. Available at http://www.itac.co.th/index.php?option=com_content&view=article & id=90.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sinfah Tunsarawuth and Toby Mendel, Analysis of the Computer Crime Act of Thailand , http://www.law-democracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/10.05.Thai_.Computer-Act-Analysis.pdf .

[17] See more in Pirongrong Ramasoota. Internet Politics in Thailand after the 2006 Coup: Regulation by Code and a Contested Ideological Terrain. In Ronald Deibert, John Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski, and Jonathan Zittrain (eds.), Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace, pp. 83-114. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012.

B. National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)’s Announcements

Historically, revolutionary decrees and coup announcements in Thailand have been seen as equivalent to laws and have had lasting effects. Because of the need for social control during such periods, many of these legal statutes are designed to specifically curb the right to free speech, particularly that of the media. Such a notion of control might have been understandable in the context of conventional media like newspapers or broadcasting, where centralized outlets of dissemination may be controlled during such problematic times. However, with the highly distributed nature of network technology like the Internet, particularly online social media that relies almost entirely on users to generate content, it is almost unthinkable to impose control upon these communication platforms.

Nevertheless, such was the case with two of the NCPO’s Announcements that emerged on the day of the coup itself, May 22nd, 2014. In Announcement No. 17/2014 entitled “The Dissemination of information via the Internet,” all Internet service providers were instructed to comply with the following:

- Monitor, investigate, and halt the dissemination of any information that may distort, incite, or instigate unrest in the kingdom or that might affect national security or public morality;

- Appear at the 2nd floor meeting room of the Office of the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) on 23 May 2014 at 10.30 hours.[18]

As a result of the second provision in the above announcement, a total of 108 Internet service providers were summoned to meet with NCPO staff at the Office of the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) on the specified date.

At the meeting, attending representatives of the ISPs were told to block public access to the Internet addresses of web pages or content deemed to be violating the coup orders, and to IPTV or live TV broadcasts relayed via Internet that were similarly in violation.

Based on news reports of the meeting, a working committee of the NCPO would inform the ISPs to block access to certain Internet addresses on a case by case basis, as the coup maker did not plan to block general online communications but rather wanted to block access only to content that violated the coup orders.[19]

In another announcement, No. 18/2014, on the topic of “Dissemination of information to the public,” all operators of mass media – print, broadcasting (terrestrial, cable, and satellite), electronic, and online social media – were asked to refrain from presenting information in the following manner:

- False information that may be defamatory, and foster hatred directed towards the royal family;

- Information that may be harmful to national security, and defamatory to another person;

- Criticism of the operations of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), its staff, and related persons;

- Voice, picture, video that may be official secrets;

- Information that may cause confusion, incitement, or instigation of unrest or division in society

- Invitation to participate in or assembly that may lead to protest against the NCPO and its staff;

- Threats to harm a person that may lead to public panic and fear.[20]

According to this Announcement, it is also mandatory for all media to disseminate information issued by the NCPO.

On July 19th, 2014, the NCPO issued another announcement which in effect merged the above two announcements into one, but with an added clause threatening sanctions. This controversial NCPO Announcement No. 97/2017 has the perceived “chilling effect” paragraph at the end, which says that, “failure to comply with orders in the announcement will result in an immediate ban of the media in question and, subsequently, legal action.”[21] This order was widely frowned upon by members of the media and general media users, who viewed the announcement not only as curbing free expression, but also as limiting individuals’ right to knowledge. After a few days of negative feedback, the NCPO decided to issue another announcement in replacement – NCPO Announcement No.103/2017 – that did away with the media ban and legal action but replaced it with a provision that forwarded problematic cases to related professional media organizations for immediate action. Additionally, the problematic content must be false and exhibit intent to discredit the NCPO to warrant action.

[18] National Council for Peace and Order Announcement No. 17/2014. In Thai (Translated by author)

[19] http://www.nationmultimedia.com/politics/ISPs-told-to-block-pages-content-seen-as-violating-30234447.html

[20] National Council for Peace and Order Announcement No. 18/2014. In Thai (Translated by author)

[21] National Council for Peace and Order Announcement No. 97/2014. In Thai (Translated by author)

C. Past Prosecution and Regulatory Measures on Internet Intermediaries

Thus far, only one case has been prosecuted relating to intermediary liability in Thailand. This was the case of the moderator of a progressive online discussion forum who was prosecuted for intermediary liability under lèse majesté - defaming members of the royal family. A summary of her arrest and trial is provided below.

1. Chiranuch Premchaiporn and Prachatai Case

Chiranuch Premchaiporn was moderator of the online discussion forum attached to an online newspaper called Prachatai. In September 2010, Chiranuch was arrested and later charged with committing an offence under Section 15 of the computer crime law, and with lèse majesté, as a result of 10 comments posted in the forum’s board that were deemed royally defamatory. According to reports, the police had notified Prachatai staff to take down the illegal content and most of the content was deleted except for a few that remained for several days.

As Chiranuch recounted in some news reports, there were too many postings to keep pace with as the forum became very dynamic in the highly volatile context following the crackdown on red-shirt protesters in May 2010. Many red-shirt supporters were frustrated and vented their anger on the Prachatai web forum, which was known to be an alternative and rather left-wing space. Participants on this board were also known to be sympathetic towards the red-shirt movements. Chiranuch went to trial in 2011, facing criminal charges since lèse majesté is an offence against national security under Section 112 of the Criminal Code. One year after the beginning of the trail, which drew significant international attention but little local coverage, in 2012 the Criminal Court found Chiranuch to be guilty and handed down a one-year prison sentence, then reduced it to an 8-month suspended prison term and a 20,000 baht (about US$680) fine.

The verdict stated that since the provision in the computer crime law did not specifically give a clear timeframe for taking down problematic content, it would be unfair to expect the web operator to preemptively delete the content. Yet, the court did not uphold the claim by the defendant (Chiranuch) that she had no knowledge of the defaming content being imported into the system because the police had notified Prachatai, yet one of the comments was left for more than 10 days before being deleted. As a web moderator, the defendant (Chiranuch) was expected to perform her duty by taking into account the intermediary liability provision. According to the verdict, illegal content that is left up for too long could lead to damages to related persons and – if disseminated irresponsibly – could cause adverse impacts to national security.

The court pointed out that there was one posting that was left on the forum’s board for a total of 20 days, which is an extensive period. The web moderator’s failure to act swiftly enough was construed as giving consent for the illegal content to remain, despite being notified. For this reason, the court ruled that the defendant was guilty as charged.

Compared to previous lèse majesté cases, this court’s ruling reflected leniency for Chiranuch, who could have faced up to 20 years in prison. For international observers from rights-based groups, the case was seen as a test of free expression involving online intermediaries in Thailand. After the eight-month suspended sentence ended, Chiranuch lodged an appeal against the verdict in 2013 and is now awaiting the result. Meanwhile, the Prachatai web board has become defunct, as the organization could not bear the costs of around-the-clock monitoring with its limited funding and staff.

D. Recommendation From Civil Society on Alleviating Impacts from Intermediary Liability

The Thai Netizen Network (TNN), a local NGO that advocates for Internet freedom and online communication rights, gave the following recommendations regarding Internet intermediary liability enforcement in Thailand:

- Internet service providers and caretakers must be classified into two groups – content-related and not content-related;

- Those providers and caretakers that are not content-related must be exempt from liability;

- A proper regulatory framework must place the liability of providers and caretakers of content-related entities in accordance with their proximity to the content;

- Regulators and law enforcement agencies must minimize the scope of impact when issuing notifications for blocking content. Those with the most proximity to the problematic content should be notified first; followed by those with less proximity. This is so that those that are closest to the content can most effectively manage the situation, while minimizing the impacts on others that are not directly related;

- Blocking access to content must be a temporary measure to alleviate the damage. Block orders can only be enforced in the presence of a court order, as a result of a charge or a lawsuit in trial. The block period must also be defined explicitly (although expandable within a time limit);

- In blocking access to content, service providers must clearly show the number of the court order on the website for public verification; and

- Content blocking must cease in cases where there is no arraignment or trial, or the lawsuit ends with a not guilty verdict. All details of the lawsuit and trial must also be publicized.[22]

IV. Research on Local Intermediaries and Their Content Practices

In order to explore first-hand how different intermediaries view the intermediary liability law and the ways that they are coping with the scheme, questionnaire-based interviews were carried out between April and June 2014 with 20 Internet intermediaries in Thailand. Of these, five were network providers, four were Internet service providers (ISPs) or access providers, and 12 were content providers.[23] The last group was comprised of hosting services, online news websites, online discussion forums, social networking services, electronic commerce websites, specialty content providers, and web portals. Names of all interviewed organizations and the interviewees cannot be provided as they agreed to be participants provided that their personal information and information about their organizations be kept anonymous. For the sake of academics, however, it may be useful to note that all the interviewed intermediaries were local operators. Effort was made to tap US-based providers of major online social networking services, but this was unsuccessful.

The interviews were structured around many salient points as experienced by network, service, and online intermediaries on content regulation, burdens incurred from intermediary liability provision, content-filtering practices, perceived impacts from the computer crime law, and the assessment of impacts from the current coup-controlled regime.

The following is a summary of these important points and the opinions of interviewees that represent the Internet/online provider sector.

- Burdens imposed on intermediaries;

- Content filtering practices;

- Types of content filtered;

- Transparency and accountability in content regulation;

- Impacts of intermediary liability provision; and

- Impacts of Internet control under coup.

[23] Network providers here refer to those operators of Internet Gateway (IIGs) as well as National Information Exchange (NIX) which rent out their networks to ISPs or general users and the scale of their service can affect the public interest. Access providers are ISPs that do not have their own infrastructure but provide access to the Internet to organizations or entities or individual users. Content providers are those that provide a variable of content services to online users and do not need to own a network to provide the services.

A. Burdens Imposed on Intermediaries

The interviewed intermediaries were asked to rate the perceived level of burden imposed on them as a result of intermediary liability provision in two aspects – allocation of resources and legal responsibility.

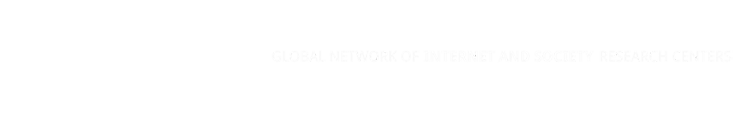

Most of tthose interviewed feel that the current burden being imposed on them regarding intermediary liability in ordinary periods is acceptable and only a few think that they are being overburdened. See Figure 1 for details.

Figure 1: level of intermediary liability burden as perceived by Internet intermediaries

However, a couple of ISPs made a critical note of the high and quite unproductive costs of having to keep traffic logs for 90 days, as well as having to install content filtering systems. In terms of human resources to patrol for content offences, at least five providers across several categories reported that specialized personnel were needed for this task. According to a couple of network and access providers, they needed to recruit new engineering staff and to develop new filtering tools to guard against problematic content. Meanwhile, operators of two online newspapers reported that they had to assign senior reporters/editors with sufficient legal knowledge to help supervise content.

As for the legal responsibility compelled by the intermediary liability provision, all access providers interviewed felt that the law is quite unreasonable to impose such liability conditions. Considering that intermediaries are not the offenders and thus could not have the intent to the commit crime, to hold them liable is unfair, according to one access provider. Most of the interviewed content providers also hold this view. While operators are expected to be vigilant to guard against problematic content, it is quite impossible in practice for this monitoring to be completely foolproof. As with any reasonable deliberation in a criminal case, they strongly feel that “the intent to commit a crime” should be a necessary basis for judicial judgment.

In addition, the interviewed providers feel that the penalties – imprisonment and fines – are not proportionate to the “offence”, which is oftentimes an unintentional error or oversight. Among the content providers, which are the category of intermediaries most apprehensive of the law, those that appear most antagonistic are those that deal with relatively sensitive content like investigative reporting and those ISPs or hosting services with online forums that thrive upon content generated by users. As reported by these interviewed content providers, most of the problematic intermediary cases they have faced are state-intermediary-user cases, rather than user-user conflicts. The latter is manifested more viably in online forums, and stems mostly from copyright infringements and defamatory remarks. However, most of these cases were sorted out or settled with the intervention of the forum moderator and very few progressed to litigation, though usually not on intermediary liability charges.

B. Content Filtering Practices

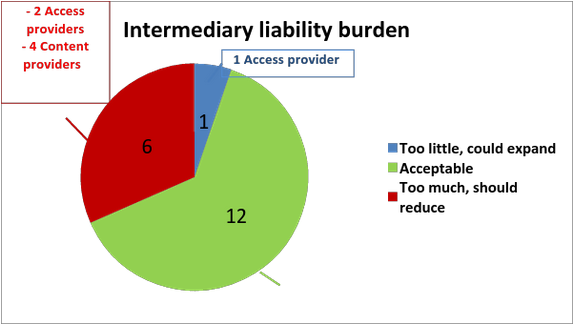

When asked about content filtering practices, it is interesting to find that network and access providers are the group that reports the highest frequency of content blocking in accordance with court orders. All the content providers interviewed said they never block content from court orders because they have never been served with one. This is understandable given the structure of Internet regulation in Thailand, in which only network providers and access providers are licensees under the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission’s system and are thus identifiable to the authority.[24] See Figure 2 for details.

In any case, court orders are usually administered through the Ministry of ICT (MICT), which is in charge of content regulation in Thailand. But since MICT does not control the licensing system, they cooperate closely with the NBTC to whom ISPs directly report.

Figure 2: Frequency in blocking websites according to court orders

Another interesting finding is that the larger the scale of the provider, the higher the rate of website blocking in accordance with court orders. From the interview in which the operators were asked to rate the frequency of the blocking based on court orders, the country’s two largest network providers both give the highest score. This correlates with a revelation about the likelihood of being served with a notice and takedown request from the authorities. The larger the operator (in terms of customer base and popularity), the more likely they are to have received notification from the authorities. Many smaller and less known websites and operators reported never having been served with a notice and take down request.

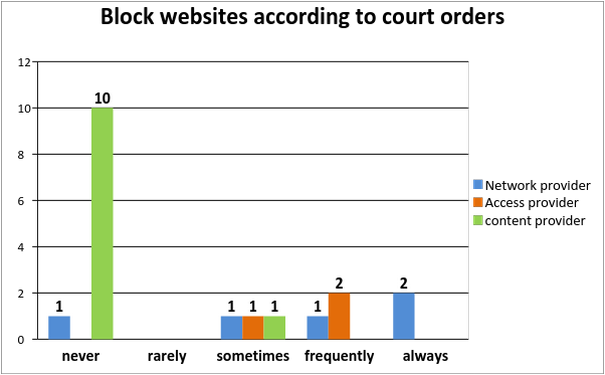

On the other hand, when asked about their content blocking and take down practices that stem from notification by officials or general users of not illegal that is not illegal (but potentially harmful) in the absence of a court order, most of the providers in all categories (though principally in the network and access provider categories) reported that they never comply with such notifications. See Figure 3 for details.

Figure 3: Taking down problematic but not illegal content according to notification by users or officials in charge, without a court order

However, some content providers that operate services with an extensive amount of user interaction, like online discussion forums, operators of the Facebook page of an online newspaper, or news blogs with readers’ comments, said that they occasionally remove content that is reported by their users who constitute a community of sorts. In this community, a certain form of self-regulation based on ethical guidelines and terms of use published by the website has taken shape, and played a role in guarding against unwanted content.

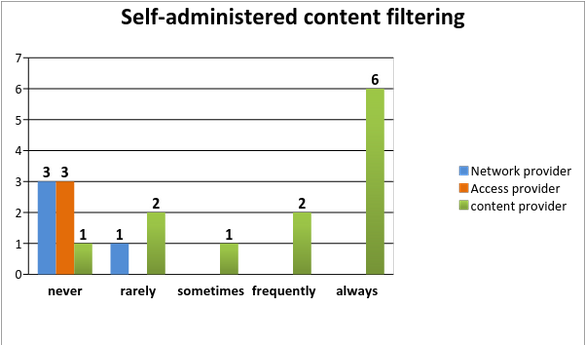

Apart from blocking as a result of court orders and taking down content without court orders, the intermediaries were also questioned about whether they administer their own content filtering systems voluntarily. See Figure 4 for details.

Figure 4: Frequency in self-administering of content filtering by intermediaries

Eight out of nineteen interviewees reported that they frequently to always administer their own content filtering. This includes three online news website operators, two online discussion forums, one specialty website, and one electronic commerce website. Their most common reason for this content filtering was to minimize the risk of lawsuits, not only stemming from content crimes but also copyright infringement and defamation.

As for network and access providers, all except one do not administer their own filtering or use their own judgment in blocking out content. This is because they feel that it is beyond their role and authority to make such decisions. The access provider that was the exception is a state enterprise, which installed a filtering system on their network many years ago. Yet, a representative from this organization reported that content is rarely blocked as a result of their independent filtering system.

[24] Under the NBTC’s Internet providers licensing system, there are two types of licenses. Type 1 license refers to license for operators who do not have their own network infrastructure and must strictly concentrate on concentrate on providing only Internet access and related services to users who are individuals, organizations, or entities, both public and private. Type 2 license is subdivided into three classes: 1) license for operators of international Internet gateway (IIGs) and national information interchange (NIX) without their own network infrastructure that render services to specific groups of customers in such a way that may not affect the larger public interest; 2) license for operators of international Internet gateway (IIGs) and national information interchange (NIX) with their own network infrastructure that service specific groups of customers in such a way that may not affect the larger public interest; 3) license for large Internet Service Providers, that may perform as IIGs or NIXs, but have a large scale of customers and their services may affect the larger public interest or free and fair competition in the market.

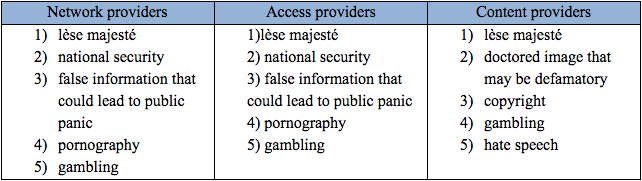

C. Types of Content Filtered

The types of content – illegal or otherwise – which different types of intermediaries report to have filtered varies somewhat in accordance with the priorities of each operator. However, lèse majesté, which is a severe offence and deeply rooted in Thai society, topped the charts of all three types of intermediaries for takedowns, followed by national security. Overall, the block list of network and access providers is indicative of the content offences outlined in Section 14 of the computer crime law. See Figure 5 for details.

Figure 5: List of top content categories blocked or removed by different types of Internet intermediaries

The similarities shared by network and access providers may be attributed to the fact that both function mainly as conduits for information and are governed under the licensing system, and are therefore in closer proximity to government’s structural regulation of the Internet. Their forbidden content list us in effect derived from the block lists issued by MICT, with or without court orders.

Meanwhile, the variation reported in the content providers’ list, with the exception of lèse majesté, can be accounted for by the specific content orientation of each website and the fact that they operate more closely to the content than network and access providers, while being more distant from the official structure of Internet regulation. In some cases, providers also take down content that is not illegal but may be harmful, such as hate speech or content related to drugs. An operator of a popular online discussion forum, for instance, gave high priority to hate speech, which has been a growing online phenomenon in Thailand despite the fact that this is not a crime under Thai law.

Another interesting observation that emerged from this part of the survey is that other than following court orders, most network and access providers usually consult with the MICT in any dubious content take down decisions. Most content providers make such decisions independently, though the few are big enough to host a legal unit will consult with their lawyers before making such decision.

D. Transparency and Accountability of Content Regulation Process

Although most interviewed intermediaries assure that they operate their content handling with transparency, only about half of those surveyed publicize or make available their content regulation guidelines or filtering process to their users. Those that do have the information available claimed to have content guidelines incorporated into their terms of use, while only a couple provide the users with information about content filtering process.

Interestingly, neither of the two network providers interviewed – a state enterprise and a private corporation – have such information available for their customers. Both justified this absence by the fact that all filtering protocols and practices are done as part of the working procedure of the Ministry of ICT. The intermediaries’ role is to just comply and render the sought co-operation. The same is true of all the interviewed access providers who claimed that all necessary information about blocking/filtering was publicly provided in the block pages of the MICT, and now the NCPO’s block page.

Most of the intermediaries studied have many channels (e.g. telephone, mailing address, online social media, and website) for users to file a complaint about their services, including a notice for content take down. However, very few provide a channel for complaints or petitions against blocked or removed content. For those network providers that do not provide such channels, they claim that the decision to block content is final as it is a legal action in accordance with court orders. If any complaint on such procedures is to be made, it must be directed to the authority that ordered the blocking, whether it is the court or the MICT-appointed officials.

Similarly, the usual content filtering procedures carried out by these intermediaries do not include notification to users or websites in cases that their content may be blocked or removed. All network and access providers state that they do not have this policy and practice in place for the same reason as above. They also feel that since they have a large base of users, it would not be feasible to circulate such notifications and that this should be the duty of content provider, not the intermediary, to do this.

Meanwhile, most content providers that do perform their own filtering also do not routinely give notification before taking down content. This is because they feel that the reason for their decision is already indicated in the terms of use and content guidelines. Of all the interviewed content providers, four claimed to occasionally notify their clients or users about content removal in cases where the offence is not legally conclusive. But in cases where the content falls clearly under the law, they will automatically remove without notifying.

Notably, of all the studied intermediaries, only the operator of a famous online discussion forum website has a standard practice of notifying users before and after content removal. Prior notice is sent directly to the individual user, with an explanation as to why his or her posting is being removed. A notice after the content takedown is also sent to each individual user after a certain number of wrongdoings are committed. This is to remind the problematic user that his or her account may be revoked as a result of these wrongdoings.

In addition, most intermediaries in the study also claimed they have in place preventive measures against business bullying or discrediting in cases of notice for content takedown from users. Some intermediaries require that the person(s) who lodged the complaint to press charges with the police to help verify the identification and credentials of the complaint filer. Others use an in-house committee to help scrutinize the complaints more thoroughly. Some content providers also have their staff investigate into past use records of the complaint filer to check their reliability. But there are quite a significant number of intermediaries, mostly network and access types, that do not have such procedures in place as they do not respond to users’ takedown notice and act only under the instruction of the MICT or a related authority.

When questioned about the integrity of their content regulation system, all intermediaries assured that they maintain good practice and good governance. While the studied network and access providers tend to emphasize data security, technological safeguards, and quality assurance systems, the content providers are more inclined to show that they adhere to professional ethics, particularly those in the online news sector. As for those non-journalistic content providers, they claim to have a transparent system that is open to scrutiny, both internally and externally. However, a couple of the intermediaries in the study feel that ensuring integrity of content regulation process should be the duty of the regulator or the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC), while another intermediary sees compliance with court orders as already sufficient to show integrity in this regard.

E. Impacts of Intermediary Liability Provisions

All intermediaries in the study admitted that the intermediary liability provision has had an impact on their work and the way they conduct their business. Apart from the increased burden mentioned earlier, many intermediaries also expressed frustration in complying with the law, which they feel is incongruous with the open and participatory nature of the Internet. According to one access provider, the main discrepancy in the law lies in holding intermediaries liable for content that is imported into the system under their care, but not giving access providers the right to filter the content independently. The authority to take down content is centralized under the court system.

Meanwhile, another access provider objected to the idea of access providers having to monitor and filter content, as this would entail tremendous and unnecessary costs. If anyone in the supply chain of Internet content should be responsible, it should be the content providers who are closest to the content.

Since the law came into effect seven years ago, at least three of the surveyed content providers said they had held regular training for their staff to educate them about provisions in the law, while a blog hosting service provider has had to assign a blog editor to supervise content within their hosting space. For online newspapers, 24-hour content monitoring became mandatory, particularly for the users’ comment section. Those who could not cope with the rising costs and burden would have to discontinue interactive functions like online forums, while others who did not have interactive features decided to maintain their online services’ one-way communication structure to minimize risks.

Over all, most of the intermediaries studied object to having the intermediary liability provision in the computer crime law. This includes almost all the network and access providers, with the exception of two that feel holding intermediaries liable is fair and will lead to more responsible use of the widely diffused and all-encompassing Internet. Those who object to the law see intermediaries as messengers or conduits of information and, thus, believe they should naturally be exempted from legal responsibility. One of the network providers argued in support of an international principle imbued in the European Cybercrime Convention that protects intermediaries, and urged that this be adopted in the new and amended version of the computer crime law.

Within the content providers’ segment, the view is split into two poles. There are those that disagree with holding intermediaries liable under any circumstances, and those that see intermediary liability as necessary, particularly for Internet applications and space that rely on user-generated content, like online public forum and comments sections. For the latter group, the malleability of the Internet, which makes it highly flexible to copy, share, and disseminate information to the widest scope of audience, is a sufficient justification for imposing liability. For this group, a website operator is comparable to a landlord. The duty of the landlord is to make sure that all tenants take good care of their own space and do not break the law while in residence.

F. Recommendations for Change in Intermediary Liability Provisions

Most of the intermediaries propose that if the law is to be amended, it should adopt an approach that protects intermediaries. These are some such suggestions as proposed by members of the intermediaries interviewed in the survey:

- Intermediaries should play a preventive role against content offences but should not be held liable;

- There should be a systematic process in proving the intent of the intermediaries in giving consent or allowing content offences to take place;

- A clarification should be made about the wording “intentionally” and “false information,” which overlap with Section 14 of the law;

- A committee or taskforce should be set up to help protect Internet intermediaries in litigation;

- If a trial takes place, there should be an injunction to protect intermediaries, possibly as witness; and

- Adaption or partial emulation of substance and implementation procedure of the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is recommended.

G. Impacts on Content Regulation After Announcement of Martial Law and the July 2014 Coup

Since the staging of the coup on 22 May 2014 and the enforcement of martial law prior to that, the Thai political and communications sector have been markedly affected. Insofar as Internet intermediaries are concerned, the impacts can be analyzed from the vantage point of two groups of providers, based on first-hand assessment, as follows.

1. Network and Access Providers

Large network providers appear to be the ones suffering the least from the change in political regime. To them, the most evident impact is the increased burden in blocking websites. However, since this is carried out under an existing scheme of content filtering, the task has been quite manageable. Moreover, network providers that are state enterprises feel that they are obliged to support the policy of the coup makers, which, to them, signifies a much-needed intervention for the sake of the country. Likewise, the state-owned provider that has a content monitoring and filtering system in place has been cooperating fully with the new authority in surveillance and censorship of content offences or misdeeds against the NCPO in the online sphere. But for a privately owned network provider, the intervention of the coup means harder and more tedious work. With more rules and regulations, political content that was not classified as an offence before has become forbidden and has risen to top priority in the block list.

As for access providers, the assessment of the post-coup impact is quite similar to network providers although with more misgivings, as most of the access providers are private enterprises. Apart from shouldering a bigger burden in blocking websites, these providers have been compelled to keep pace with new announcements of the NCPO that are related to their operation, assign more staff to do round-the-clock patrolling of the network, and attend meetings with different authorities, including the NBTC and MICT. A foreign-owned access provider voiced the opinion that, despite their objection to the NCPO’s blocking scheme that came in place of the court orders of the past, they are not in a position to defy it. Although they could clearly see the unfairness in blocking certain websites, they have had to comply and reserve their judgment.

2. Content Providers

The situation is quite different for content providers, particularly those that deal with political content and user-generated content. Two online newspapers and one web portal had to close down an interactive section for readers’ comments, and the operator of an online discussion forum has been forced to remove an unprecedentedly high number of postings from the political discussion board. As a result, the scope of political discussions has become very limited and constrained. While the operator wishes to keep the forum open so that people would have space for exchange and release of political tension, people have become reluctant to participate because of the high level of censorship and the climate of fear. In addition, this operator has also tightened up the self-regulation scheme enforceable through the website’s online community to guard against objectionable materials.

Meanwhile, the operator of a Facebook page for an online newspaper admitted that a much more meticulous process has been introduced to filter content prior to publication. All news, articles and commentaries must refrain from criticism of the NCPO to avoid being shut down. The basic rule is to stick to the facts, and avoid opinions and comments. Therefore, self-censorship has become the mantra of the day.

For those content providers with no interactive function, the impact has been quite minimal but they still proceed with much care. Two online investigative reporting websites reported that their news production and workflow had not been much affected, but they had to exercise extreme caution in choosing topics for investigation and in wording political content. For those specialty websites, electronic commerce, and web portals that have no bearing on politics, the only tangible impact is that there are more users and greater traffic than ever before. This is attributed to the fact that the spaces for political exchange and dialogue have shrunk, so websites that appeal to human interest have taken over in prominence.

V. Conclusion

On the one hand, the wording in Section 15 of the Thai computer crime law may be enough to exercise a chilling effect on every Internet intermediary. On the other hand, one prosecution after seven years does sound like a track record of leniency on the part of law enforcement. Intermediary liability in Thailand is indeed more complex than it seems for many reasons.

First, the structure of the Internet industry still contains viable remnants of state ownership and control from the past. While the survey data may not be all telling due to the need to comply with the interviewee’s anonymity requirements, major Internet service providers in Thailand largely comprises of state enterprises, private corporations that have thrived on government concessions since the 1990s, and new players that came after the frequency reform in the mid-2000s. Within this context, these dominant players have been well disciplined to cooperate with the state’s Internet regulation scheme that favors surveillance and censorship.

Over the course of the past two decades, a culture of censorship has gradually been established in which the Ministry of ICT is highly instrumental. Since this culture has been breeding an air of control and co-optation with the state, the emergence of the computer crime law and the provision on intermediary liability did not seem to represent a major change or pose as a major threat to these operators. So long as they are disciplined partners with the state on content-related issues complying with the culture of surveillance and censorship, they will not be targets of intimidation and control under the new law.

Unfortunately, such is not the case with the new wave of Internet content providers or online service providers that focus on providing content, as well as spaces where users can generate content on an open and participatory architecture of Web 2.0 Internet platforms – blogs, online forum, social networking services, among others. In the context of Web 2.0 communications, online content intermediaries have become important agents of control. So, governments – democratic and dictatorial – are passing on the censorship and surveillance role to these agents, whether they like it or not. The grave concern expressed and the real impacts felt by the studied content intermediaries after the May 2014 coup reflect the tremendous challenges facing this sector of intermediaries, who are generally smaller and less endowed with resources than the network and access providers to consistently cope with demands of the authority to guard against objectionable content.

Secondly, laws and the market regulate the Internet consistent with prevailing norms in Thailand, particularly ones that are inherent and socially shaping, like reverence for the monarchy. This is clearly reflected in the only case of intermediary liability prosecution involving the Prachatai online discussion forum. Not only does Prachatai represent a new wave of online content intermediaries that are markedly different from the conventional network and access providers as mentioned above, but Prachatai also represents a dissident online medium, since much of the website’s content reflects progressive thinking and advocacy for changes from the status quo. And, perhaps it is for this reason that Prachatai was chosen to be an exemplar of the chilling effects of the computer crime law in the Thai Internet landscape.

It must not be forgotten that the charges filed against Prachatai covered both intermediary liability and lèse majesté, which is a severe offense in Thailand. The lèse majesté offence is also indicative of the underlying norms and values in Thai society – reverence of the monarchy and intolerance of criticism. This largely explains why local media or critics have not been very vocal in advocating for the cause of free expression in the trial of Prachatai’s web forum moderator. While free speech is high on the priority list of mainstream media in Thailand, Prachatai was not viewed as part of the group warranting such protection. As an alternative online media accused of breaching a draconian law, the case has slipped from the public eye. In effect, intermediary liability was superseded and overshadowed by lèse majesté, and the conventional and dominant understanding about what constitutes the media.

Nevertheless, the looming chilling effects brought upon by the intermediary liability provision are still real and made even more real by the recent change of political regime, and the unprecedented curbing of people’s free expression. To recap, NCPO issued a couple of announcements targeting dissemination of information via online social media.

Overall, since the recent coup the mode of regulation for online intermediary has shifted markedly from self-regulation to top-down sanction through an ad hoc body – the CSOC – that operates in a highly command and control fashion. The governance mechanism has also shifted from a criminal liability approach, as would be the case under the computer crime law, to upfront prior restraints associated with surveillance and censorship schemes. These constraining mechanisms appear to be more ex ante than ex post.

Under coup-shaped conditions, it is viable that coup announcements – which are equivalent to laws – have prevailed over other regulatory elements – market, code, or social norms – in the governance of Thai cyberspace. In this unusual and often regarded as temporary context, freedom of expression is not viewed necessarily as a crime, but more as something that needs to be curbed for the good of the country in its transitory path towards national reform.