Online Intermediaries in India

This case study by the National Law University, Delhi maps and analyzes online intermediary liability in India by describing the landscape, highlighting intermediaries of special interest such a platforms used to arrange marriages, mapping the online intermediary governance mechanisms, and assessing the impact of the governance framework.

Online Intermediaries in India

Authors: Chinmayi Arun and Sarvjeet Singh

National Law University, Delhi

Abstract: This case study maps and analyzes online intermediary liability in India. It begins with the landscape of online intermediaries in India, highlighting intermediaries of special interest. This includes, for instance, platforms used to arrange marriages, which are much more popular in India than dating platforms because of Indian social norms. The second section of the paper attempts to map in detail the governance mechanism applicable to online intermediaries in India – this includes the licensing system used for internet service providers, the Information Technology Act, and the Copyright Act. The likelihood of generally applicable criminal law in India (such as the Indian Penal Code) as a potential source of intermediary liability is also discussed briefly. The final part of the paper assesses the impact of the governance framework, ties together its different themes of content blocking, interception of data, and notice and takedown of content. It analyzes the law under which these activities take place, from the perspective of good governance principles such as transparency and accountability. It also considers whether the governance framework for online intermediaries treats online speech in a manner that is consistent with the Indian constitution. The serious flaws in the systems followed in India are apparent through this assessment – the lack of transparency and accountability suggest that over-regulation of constitutionally protected speech is likely to result in very little protection of primary speakers’ rights.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

A. Top Websites in India

1. Search Engines

2. Social Media Websites

B. Intermediaries of Interest in India

II. Governance mechanism & Legal Framework for Intermediary Liability in India

A. Licensing System for Internet Service Providers

B. The Information Technology Act, 2000

1. Safe Harbor, ‘Due Diligence’ and Editorial Control

2. Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules, 2011

3. Blocking Orders Under the IT Act

4. Interception Under the IT Act

C. The Copyright Act, 1957

III. Impact Assessment

A. Government-Ordered Blocking of Content

B. Notice and Takedown

C. Interception of Information by Intermediaries

IV. Cases currently before the Supreme Court

A. Rajeev Chandrasekhar

1. Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules, 2011

B. Common Cause

1. Section 69A and the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009

C. Moutshut.com

D. Peoples' Union for Civil Liberties

1. Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009

2. Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011

E. Internet and Mobile Association of India

1. Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011

F. Kamlesh Vaswani

I. Introduction

The intermediary eco-system in India is still evolving. At a glance, it is apparent that the major online intermediaries in India are familiar global names. This is not surprising given the demographic that is currently accessing the Internet in India: digital access is concentrated in urban areas, and among literate people who are familiar with the languages used by international online platforms.

This paper begins with an attempt to outline the significant online intermediaries operating in India and the market share held by each. It also highlights some interesting online intermediaries, like CGNet Swara, that are significant for reasons other than market share. CGNet Swara is a hybrid platform catering to parts of rural India, allowing tribal people to create news reports using a simple voice mobile phone connection. Indian social norms also generate their own versions of global online platforms. While dating websites are ubiquitous globally, their Indian counterparts focus on ‘arranging’ marriages using criteria like caste, religion and skin-color, which are significant factors in what is referred to popularly as the ‘marriage market’.

The second part of the paper discusses the regulatory framework that governs intermediary liability in India. It outlines very briefly the constitutional framework within which intermediaries operate. It then proceeds to offer an indication of the criminal and civil liability that might apply to intermediaries without safe harbor protection. This safe harbor protection comes from the Information Technology Act, which offers conditional immunity to intermediaries. This immunity and the conditions attached to it – including intermediaries’ obligations in the context of content blocking, interception of information, and notice and takedown – are discussed in some detail in this part. Also discussed is the Copyright Act’s different safe harbor framework and the ex parte court copyright-infringement related orders that are increasingly prevalent in India.

The third part of this paper builds on the facts set out in the second part by offering an analysis, supported with data wherever possible, of the impact that the regulatory framework has on online intermediaries and the content that they are willing to host. This part of the paper considers the transparency and accessibility of the legal rules, in order to assess whether intermediaries are easily able to understand what they need to do to comply. It examines the framework’s incentives to see whether a chilling effect is created. It also considers the transparency and accountability of government ordered blocking and interception to evaluate whether this liability regime offers any safeguards from censorship or surveillance by proxy.

The notice and takedown process set up under the Information Technology Act (IT Act) and the Copyright Act are controversial especially in terms of the chilling effect that they have on speech. Also of concern are several petitions currently before the Supreme Court of India. While some of these petitions seek to strike down the notice and takedown regime set up by the IT Act on grounds that it violates constitutional rights, others seek to reinstate a strict liability regime for obscene content online. The Supreme Court’s ruling in these cases will shape the future of intermediary liability law in India. They are introduced at the end of this piece.

India currently has the world's third largest Internet consumer base after China and the United States[1], with a total of 238.71 million subscribers as of December 2013[2] and 205 million users as of October 2013[3]. However, the number of active Internet users (i.e. users accessing the Internet at least once a month) was a much lower 149 million as of June 2013[4]. The users’ engagement with the online space is also low, with Internet users in India spending only 20 to 25 hours on average online per month.[5]

[1] Moulishree Srivastava, Internet base in India crosses 200 million mark, Mint (Nov. 13, 2013), http://www.livemint.com/Consumer/9pWsphmYL2YjdisfO7bGLM/Internet-base-in-India-crosses-200-million-mark.html.s

[2] Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators: April - June, 2013, xii, 27 (Dec. 2013), available at http://www.trai.gov.in/WriteReadData/PIRReport/Documents/Indicator%20Reports%20-%20Jun-02122013.pdf.

[3] Internet Users in India Crosses 200 Million Mark, IAMAI (Nov. 13, 2013), http://www.iamai.in/PRelease_detail.aspx?nid=3222&NMonth=11&NYear=2013.

[4] IAMAI Internet in India 2013, Internet and Mobile Association of India, 2 (2013).

[5] Chandra Gnanasambandam and Anu Madgavkar, Online and upcoming: The Internet’s impact on India, McKinsey & Company (Dec. 2012), available at http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_Internet/indias_Internet_opportunity.

A. Top Websites in India

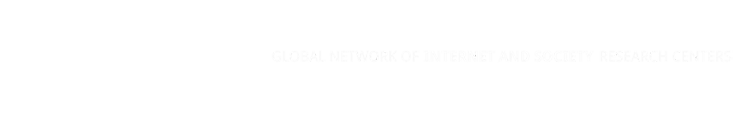

The top websites in India, according to commercial web traffic data collected by Alexa, an analytical website, are as follows:[6]

Figure 1. Top Websites in India

This data indicates that thirteen of the top fifteen websites are based outside India. The two exceptions are flipkart.com (an online retailer that reaches markets similar to those targeted by Amazon) and indiatimes.com (a content portal owned by Indian media company Bennett, Coleman and Co. Ltd.).

[6] Top sites in India, Alexa (July 24, 2014), available at http://www.alexa.com/topsites/countries/IN.

1. Search Engines

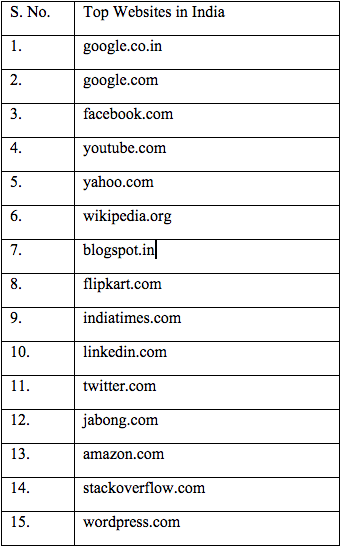

Figure 2. Search Engines (Data from StatCounter)

[7] Top 5 Search Engines in India from June 2013 to June 2014, available at http://gs.statcounter.com/#all-search_engine-IN-monthly-201306-201406.

2. Social Media Websites

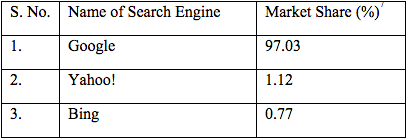

Figure 3. Social Media Websites (Data from StatCounter)

Facebook has the largest user base in India with 93 million users, followed by Twitter with its estimated 33 million accounts,[10] and LinkedIn, which has 24 million users.[11] According to the Comscore India Digital Future in Focus Report 2013, Facebook is the most popular social media site in India, capturing the maximum screen time with access to 86% of the user base in India and 59,642,000 unique visitors in 2012-2013.[12] The report suggests that Facebook is followed by LinkedIn, which is the next most popular, with 11,127,000 visitors, followed by Twitter, which had 3,884,000 unique visitors.[13] An IAMAI report suggests that 96% of the total number of social media users use Facebook, while 57% use Google plus, and 49% use Orkut.[14] The video-sharing platform YouTube has over 55 million unique users a month in India[15], and is used by 58% of 137 million Internet users in the country.[16]

[8] The data combines Micro blogs, Social media; User generated content platforms types of intermediaries as provided in the guiding questions document.

[9] Top 7 Social Media sites in India from June 2013 to June 2014, available at http://gs.statcounter.com/#all-social_media-IN-monthly-201306-201406.

[10] Atish Patel, India's social media election battle, BBC News India (Mar. 31, 2014), http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-26762391.

[11] LinkedIn India user base crosses 24 million; 277 million members worldwide, NDTV (Feb. 12, 2014), http://gadgets.ndtv.com/social-networking/news/linkedin-india-user-base-crosses-24-million-277-million-members-worldwide-482512.

[12] India Digital Future in 2013, ComScore, 24 (Aug. 22 2013), available at http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Presentations_and_Whitepapers/2013/2013_India_Digital_Future_in_Focus.

[13] India Digital Future in 2013, ComScore, 24 (Aug. 22 2013), available at http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Presentations_and_Whitepapers/2013/2013_India_Digital_Future_in_Focus.

[14] Social Media in India – 2013, Internet and Mobile Association of India, 6 (Oct. 2013).

[15] N Madhavan and Vivek Sinha, We have 10,000 full-length Indian movies on YouTube: Google India chief, Hindustan Times (Sept. 17, 2013), http://www.hindustantimes.com/business-news/we-have-10-000-full-length-indian-movies-on-youtube-google-india-chief/article1 1123030.aspx.

[16] Rohin Dharmakumar, Is Google Gobbling Up the Indian Internet Space?, Forbes India (Jul. 22, 2013), http://forbesindia.com/article/real-issue/is-google-gobbling-up-the-indian-Internet-space/35641/0#ixzz38Kf8IuNP.

B. Intermediaries of Interest in India

There are many intermediaries in India that were created in response to Indian social norms and markets. These include online matrimonial portals, which resemble online dating services in some ways, but have other design choices and actual functions that cater to Indian social norms. The first of these matrimonial portals began operation in 1996 and was called sagaai.com (subsequently shaadi.com),[17] owned by People Group. The online matrimony market is currently valued at around $83,000,000[18] and is expected to touch $250,000,000 by 2017.[19] In deference to widespread Indian practices about marrying within particular sub-groups, these portals enable users to search for matches based on religion, caste, mother tongue, horoscope, skin tone, vegetarianism, alcohol consumption, and smoking habits. They enable parents to set up profiles for their offspring, allowing for the fact that many families ‘arrange’ marriages for young people and see the choice of partner as a family decision rather than an individual one. The consequence of this can be a violation of privacy and professional embarrassment for people who find that a wedding profile has been created for them without their consent. However, it is difficult to find lawsuits or complaints about these incidents since they take place between close family members and are usually handled informally. A more serious and fairly common problem in the context of matrimonial websites is fraud. News reports suggest that there are multiple cases of women and their families being duped by men who use these platforms to extort money by misrepresentation or blackmail.[20] The Government has issued a press release reminding these intermediaries of their obligation to disable harmful and unlawful information when it is reported, and to appoint Grievance Officers to assist with this process. [21] The press release also mentions the Indian Computer Emergency Response team works with social networking websites to disable fake accounts, and that this is more easily achieved for social networking websites with offices in India.[22]

In non-urban India, new platforms are being set up to bridge the digital divide even though broadband connectivity is still not available in these regions. [23] These platforms include initiatives like CGNet Swara, Kanoon Swara, and Graam Vani. CGNet Swara allows people in rural areas of central India with majorities of tribal populations to submit and listen to audio news reports regarding the area. The initiative receives an average of 200 calls per day and is driving the emergence of online reports on local issues.[24] The Gram Vaani[25] operates a Mobile Vaani initiative that connects reports from mobile phone users to stakeholders including governments and NGOs using an interactive voice response system. In the state of Jharkhand, it has over 100,000 users that call 2000 times a day.[26]

Online recruitment websites such as ‘naukri.com’ and ‘monster.com’ have also gained immense popularity in India.[27]

[17] Satrajit Sen, Arranged marriages over the Internet were a laughable idea when Shaadi.com started, India Digital Review (Dec. 5, 2011), http://www.indiadigitalreview.com/interviews/arranged-marriages-over-Internet-were-laughable-idea-when-shaadicom-started-anupam-g-mitt.

[18] Harsimran Julka & Apurva Vishwanath, Matrimony portals making serious efforts to counter rising tide of divorces, ensure lasting unions, Economic Times (June 26, 2013), http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-06-26/news/40206906_1_portals-online-bharatmatrimony-com.

[19] Online marriage business may touch Rs.1,500 crore by 2017: Assocham, India Today (Dec. 18, 2013), http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/online-marriage-business-may-touch-rs-1500-crore-by-2017-assocham/1/331691.html.

[20] Sadaf Aman, Frauds and Cheats Rule Matrimonial Sites, New Indian Express, http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/hyderabad/2014/11/24/Fraud-and-Cheats-Rule-Matrimonial-Sites/article2537595.ece, last visited on 8th January 2015.

[21] Steps to Prevent Frauds by Social Networking Sites and Matrimonial Sites, Press Information Bureau (21 Feb., 2014) http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=104142.

[22] Steps to Prevent Frauds by Social Networking Sites and Matrimonial Sites, Press Information Bureau (21 Feb., 2014) http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=104142.

[23] As of 2013 only 60 million of the 190 million total Internet users were from rural India: IAMAI Internet in India 2013, Internet and Mobile Association of India, 2 (2013); The teledensity in rural areas is approximately 43 percent as compared to 140 percent teledensity in urban areas: TRAI, Highlights on Telecom Subscription Data as on 30th April, 2014, Press Release No. 35/2014 (June 26, 2014), http://www.trai.gov.in/WriteReadData/PressRealease/Document/PR-TSD-Apr,14.pdf.

[24] India: Use Mobile Technology to Bring News to Isolated Tribal Communities, International Centre for Journalists, http://www.icfj.org/knight-international-journalism-fellowships/fellowships/india-using-mobile-technology-bring-news-is-0.

[25] Graam Vaani: About Us, http://www.gramvaani.org/?page_id=76.

[26] How Mobile Vaani Works”, http://www.gramvaani.org/?page_id=15.

[27] Rebirth of e-Commerce in India, Ernst and Young (2013), available at http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Rebirth_of_e-Commerce_in_India/$FILE/EY_RE-BIRTH_OF_ECOMMERCE.pdf.

II. Governance mechanism & Legal Framework for Intermediary Liability in India

Online intermediaries are subject to a fairly complex regulatory framework in India, which leaves them open to civil and criminal liability. The most significant laws governing intermediaries may be found in the Information Technology Act, 2000, and the Copyright Act, 1957. However there are circumstances in which more generally applicable legislation, such as the Indian Penal Code (1860), the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989), the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (2012), as well as the law of torts, may apply. If an online intermediary is not eligible for immunity from liability offered by the IT Act[28], it could incur civil or criminal penalties for offences such as defamation[29], obscenity[30], sedition[31], and/or copyright claims[32].

The regulatory approach thus far is largely command and control, as is typical of the Indian legal system. However, this seems to be changing gradually as the architectural constraints of the Internet become more apparent. Online intermediaries, unlike Internet service providers (ISPs), cannot be subject to the domestic licensing regime, given that several of them do not have offices in India and are therefore out of the physical jurisdiction within which the Indian Government is easily able to implement its laws. Therefore, although ISPs are subject to several obligations through their licenses (discussed below in 2.1), international online intermediaries remain free of these constraints.

[28] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79 (prior to the Information Technology Amendment Act, 2008).

[29] The Indian Penal Code, 1860, § 499; Khushwant Singh and Anr. v. Maneka Gandhi, A.I.R. 2002 Delhi 58 (India); Ratanlal and Dhirajlal, The Law of Torts 279 (26th ed. 2013).

[30] The Indian Penal Code, 1860, § 292, The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 67.

[31] The Indian Penal Code, 1860, § 124A.

[32] The Copyright Act, 1957, § 51.

A. Licensing System for Internet Service Providers

Internet service providers are required to get licenses in India, and are subject to several obligations through their license terms. Content intermediaries, however, do not have to get licenses for operation, and one of the reasons for this might be that it would be very difficult to enforce such a requirement on intermediaries located in other jurisdictions. Of the various types of Internet intermediaries, it is telecommunication service providers, network service providers, and Internet service providers that require a license to offer services in India.

The regulatory framework for intermediaries originates in the Indian Telegraph Act,[33] which empowers the Central Government to issue licenses to establish, maintain, or work a telegraph.[34] The Department of Telecommunication acts as a licensor on behalf of the Central Government, and enters into agreements with companies for the provision of telecommunications and Internet Services.

There are three types of licenses for communication providers in India: The License Agreement for Provision of Internet Services (‘ISP License’)[35] The License Agreement For Provision Of Unified Access Services after Migration from CMTS (‘UAS License’)[36] * The License Agreement for Unified License (‘Unified License’)[37]

The Government has taken to issuing only Unified Licenses since 2012. This might be an effort to consolidate and simplify the licensing process, since the Unified License covers various telecom services such as Access, Internet, and Long Distance within a single license.[38] It contains a separate chapter for Internet Services. The licenses obligate licensee-intermediaries to block Internet sites, Uniform Resource Locators (URLs), Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), and/or individual subscribers, as identified and directed by the government in the interest of national security or public interest from time to time.[39] The licenses also declare that carriage of objectionable, obscene, unauthorized, or any other content, messages, or communications infringing copyright and intellectual property rights etc., in any form, is not permitted, and obligates licensees to prevent such carriage when specific instances are reported.[40]

The license agreements contain a number of provisions concerning data retention, disclosure, and the provision of services to enable surveillance.[41] They require ISPs to put in place systems that enable lawful monitoring and interception of communications by the Indian Government.[42] ISPs are also required to trace or monitor content such as communications that are obnoxious, malicious, or a nuisance[43], and ‘objectionable’ communications.[44]

At every international gateway or node having an outbound capacity of more than 2 MB/s, ISPs are required to set up monitoring centers equipped with appropriate monitoring systems in accordance with government specifications[45], office space[46], telephone lines[47], and be accessible to monitoring agencies at all times.[48] ISPs must also facilitate Government access to various equipment, leased lines, record files, and logbooks of the ISPs.[49] Additionally, periodic inspections of Internet leased line customers at their premise are to be performed by the ISP within 15 days of commissioning an Internet line to check for possible misuse.[50]

The UAS & Unified Licenses require licensee service providers to provide the “necessary facilities” to the Government to “counteract espionage, subversive acts, sabotage, or any other unlawful activity”.[51] All three licenses obligate licensees to “facilitate” the application of Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act, which deals with interception of communication.[52]

[33] The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, § 4.

[34] The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, § 3 (1AA).

[35] Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[36] Licence Agreement for Provision of Unified Access Services after Migration from CMTS , http://www.auspi.in/policies/UASL.pdf.

[37] License Agreement for Unified License , http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unified%20Licence_0.pdf.

[38] Department of Telecommunications, Unified License, http://www.dot.gov.in/licensing/unified-license.

[39] Chapter IX clause 7.12, License Agreement for Unified License, http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unified%20Licence_0.pdf clause 7.12, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[40] Chapter V clause 38.1, License Agreement for Unified License, http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unified%20Licence_0.pdf clause 33.6, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[41] Chinmayi Arun and Ujwala Uppaluri, Research Memorandum Concerning The Indian Surveillance Framework for iProbono (2014).

[42] Chapter IX clause 8.1.1, License Agreement for Unified License, http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unified%20Licence_0.pdf.

[43] Clause 33.4, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[44] Clause 33.6, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.; Chinmayi Arun and Ujwala Uppaluri, Research Memorandum Concerning The Indian Surveillance Framework for iProbono (2014).

[45] Clause , Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf. 34.27(a)(i).

[46] Clause 34.27(a)(ii), Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[47] Clause 34.27(a)(iii), Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[48] Clause 34.27, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[49] Clause 30.1, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[50] Clause 34.17, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[51] Clause 41.1, Licence Agreement for Provision of Unified Access Services after Migration from CMTS , http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf.

[52] Clause 40.1, License Agreement for Unified License, http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Unified%20Licence_0.pdf; clause 35.1, Licence Agreement for Provision of Internet Services, http://cca.ap.nic.in/i_agreement.pdf; clause 42.1 Licence Agreement for Provision of Unified Access Services after Migration from CMTS , http://www.auspi.in/policies/UASL.pdf.

B. The Information Technology Act, 2000

The Information Technology Act, 2000 (referred to as ‘IT Act’) came into force on 17 October 2010 and was meant to provide legal recognition of electronic commerce.[53] It was also meant to give effect to a UN General Assembly resolution on Model Law on Electronic Commerce adopted by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law.[54] The IT Act was amended in 2008[55] in a manner that expanded the safe harbor protection significantly, thereby changing the intermediary liability regime substantially. The amendment emerged after the Report of the Expert Committee on the Proposed Amendments to the IT Act, 2000 suggested certain reforms, which would also ensure that the law relating to intermediary liability had more clarity and was closer to the framework in the EU E-Commerce Directive 2000/31/EC[56], which was used to guide the revision of the IT Act.[57]

The IT Act, prior to amendment, protected intermediaries from liability[58] in a very limited manner. The immunity extended to a narrow set of intermediaries: it was provided only to a ‘network service provider' which was defined as an intermediary, which in turn was defined as ‘any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that message or provides any service with respect to that message.'[59] Additionally, protection was offered only with respect to offences committed under the IT Act, leaving intermediaries open to liability under other legislation for content that they hosted.

One of the concerns raised was that offering only ‘network service providers’ protection from liability might leave out a range of online intermediaries[60], including the ones that provide online credit validation services.[61] It has also been argued that ‘messages’ were the only kind of content to which the safe harbor liability protection applied, and depending on how the term ‘message’ is interpreted, this may have narrowed the scope of the protection offered.[62] However, these concerns do not apply anymore, since the IT Act has been amended to expand both the immunity and the definition of the intermediaries that may claim this immunity.

Intermediaries with respect to electronic records are defined under the amended Section 2(w) of the Information Technology Act as “any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that record or provides any service with respect to that record and includes telecom service providers, network service providers, Internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online-auction sites, online-marketplaces, and cyber cafes” [63]. This was hailed by some commentators for its wider and clearer definition of intermediaries, which unambiguously included online intermediaries within its purview.[64] Others have pointed out that that although this new definition expands the number of entities that can claim safe harbor protection under the IT Act, it fails to make allowances for the functional differences between the different kinds of intermediaries.[65]

Section 2(w) includes a variety of very different intermediaries, such as telecom service providers, network service providers, Internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online-auction sites, online-marketplaces or cyber cafes, in its scope. The obligations under the IT Act are such that all these intermediaries, online or offline, are subject to exactly the same legal regime.

Differential obligations may apply to different kinds of intermediaries owing to regulations that may be specific to their particular function, such as licenses for ISPs or banking regulations for financial intermediaries. However, the safe harbor protection for intermediaries includes immunity from liability under other legislations, and therefore intermediaries that meet the conditions for immunity in section 79 of the IT Act all get immunity and find themselves in a similar position regardless of their specific role or nature. It has been argued that by not taking into account the functional differences of the intermediaries, the efficacy of the immunity may be compromised.[66]

[53] The Information Technology Act, 2000, preamble (prior to the Information Technology Amendment Act, 2008).

[54] G.A. Res. 51/162, Model Law on Electronic Commerce, U.N. Doc. A/RES/51/162 (Jan. 30, 1997).

[55] The Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008.

[56] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (June 8, 2000), available at http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0031:En:HTML.

[57] Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communications & Information Technology, Government of India, Report of the Expert Committee on Proposed Amendments to Information Technology Act 2000, 46 (Aug. 2005), available at http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Information%20Technology%20/bill93_2008122693_Report_of_Expert_Committee.pdf; Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communications & Information Technology, Government of India, Summary of the Report of the Expert Committee on Proposed Amendments to Information Technology Act 2000, ¶ 17 (Aug. 2005), available at http://deity.gov.in/content/report-expert-committee-amendments-it-act-2000-3.

[58] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79 (prior to the Information Technology Amendment Act, 2008).

[59] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 2, cl. w (prior to the Information Technology Amendment Act, 2008).

[60] Apar Gupta, Commentary on Information Technology Act 295 (2nd ed. 2011); Thilini Kahandawaarachchi, Liability of Internet Service Providers for Third Party Online Copyright Infringement: A Study of US and Indian laws, 12 J. I.P.R. 553, 559 (2007); Priyambada Mishra and Angsuman Dutta, Striking a Balance between Liability of Internet Service Providers and Protection of Copyright over the Internet: A Need of the Hour, 14 J. I.P.R. 321, 324 (2009); Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120 (Dec. 2013); See generally Aditya Gupta, The Scope of Online Service Providers' Liability for Copyright Infringing Third Party Content under the Indian Laws- The Road Ahead, 15 J. I.P.R. 35, 37 (2010).

[61] Apar Gupta, Commentary on Information Technology Act 295 (2nd ed. 2011).

[62] Apar Gupta, Commentary on Information Technology Act 295 (2nd ed. 2011).

[63] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 2, cl. w.

[64] Aditya Gupta, The Scope of Online Service Providers' Liability for Copyright Infringing Third Party Content under the Indian Laws- The Road Ahead, 15 J. I.P.R. 35, 37 (2010).

[65] Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120, 122 (Dec. 2013).

[66] Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120, 122 (Dec. 2013).

1. Safe Harbor, ‘Due Diligence’ and Editorial Control

The amended safe harbor provision under Section 79 allows a wide spectrum of intermediaries to seek safe harbor protection from liability for any third party information, data, or communication link hosted by the third party. Section 79 ensures that the intermediaries’ immunity from liability prevails over all other laws in force,[67] except for the Copyright Act and the Patents’ Act[68].

To be granted immunity under section 79, the intermediary must:

- Merely provide access to a communication system over which information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored or hosted;[69] or not initiate the transmission, select its receiver, or select or modify the information contained in the transmission[70]; and

- Observe due diligence[71] as provided by rules promulgated by the government in 2011.[72]

The use of the word “or” between the first two conditions stated above means that they are disjunctive in nature and only one needs to be satisfied in order for the intermediary to be granted immunity, along with fulfilling the third condition.[73]

Some commentators suggest that section 79 uses both the “mere conduit” and the “caching” principles, borrowed from the EU E-commerce Directive,[74] whereas others point out that the language explicitly only discusses the mere conduit principle.[75] What is clear upon examination of section 79 is that to be eligible for immunity, the intermediary has to confine itself to transmission of information and not initiate transmission, select the receiver, or modify the information.[76] Services that would clearly be covered here because of their conduit function include telecommunications carriers, ISPs, and other backbone services.[77] However, caching services should also be included since they do fall within the definition of an intermediary under the amended IT Act (which includes those who store and host information),[78] and the immunity under section 79 seems to extend to all intermediaries with no specific exclusion of caching services. There is no reason why service providers who offer hosting services and do not fall afoul of the preconditions to the safe harbor protection should not qualify for immunity under section 79.

Wielding editorial control would almost certainly cause an intermediary to be excluded from the safe harbor protection. For one thing, it would amount to selection of information, such that the intermediary will fail one of the pre-requisites listed in Section 79(2).[79]

Controversially, the immunity from liability granted by section 79 is contingent upon intermediaries observing ‘due diligence’.[80] This standard has been outlined in multiple cases, and the obligations that it entails are listed in detail in the Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011. The implications of this standard are discussed in more detail in the section on Intermediaries Guidelines below.

However, there are other ways in which even intermediaries that perform purely conduit or hosting services might find themselves liable, despite section 79. Section 79(3) limits the immunity offered by section 79, by outlining the circumstances under which an intermediary will be forbidden from claiming immunity:

- If the intermediary has conspired or abetted in the commission of the unlawful act.[81] This means that if the intermediary is involved in the commission of offence in any way then it cannot claim exemption from liability;

- Or upon receiving actual knowledge about any unlawful content the intermediary fails to remove the content alleged to be infringing.[82]

The precise meaning of ‘actual knowledge’ is unclear upon a bare reading of the statute — it is not defined in the IT Act,[83] and it remains unclear, for example, whether a notice from any private party would automatically imply that the intermediary under question now has ‘actual knowledge’ of the unlawful content. This is a standard discussed in more detail in the Intermediaries Guidelines, which also uses the ‘actual knowledge’ standard.

[67] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 1.

[68] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 81.

[69] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 2(a).

[70] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 2(b).

[71] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 2(c).

[72] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011.

[73] Super Cassettes Industries Ltd v. MyspaceInc, M.I.P.R. 2011 (2) 303 (India).

[74] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (June 8, 2000), available at http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0031:En:HTML; Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120, 121-22 (Dec. 2013).

[75] Rishabh Dara, Intermediary Liability in India: Chilling Effects on Free Expression on the Internet, Centre for Internet & Society 20-23 (Apr. 10, 2012), available at http://cis-india.org/Internet-governance/intermediary-liability-in-india.

[76] See also Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120, 122 (Dec. 2013).

[77] Rajendra Kumar and Latha R. Nair, Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Copyright Act, 1957: Searching for the Safest Harbor?, 5 NUJS L. Rev. 554, 562 (2012).

[78] S. 79. Exemption from liability of intermediary in certain cases.—(1)Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force but subject to the provisions of sub-section (2) and (3), an intermediary shall not be liable for any third party information, data, or communication link made available or hosted by him.

(2) The provisions of sub-section (1) shall apply if—

(a) the function of the intermediary is limited to providing access to a communication system over which information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored or hosted; or

(b) the intermediary does not—

(i) initiate the transmission,

(ii) select the receiver of the transmission, and

(iii) select or modify the information contained in the transmission;

(c) the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging his duties under this Act and also observes such other guidelines as the Central Government may prescribe in this behalf.

(3) The provisions of sub-section (1) shall not apply if—

(a) the intermediary has conspired or abetted or aided or induced, whether by threats or promise or otherwise in the commission of the unlawful act;

(b) upon receiving actual knowledge, or on being notified by the appropriate Government or its agency that any information, data or communication link residing in or connected to a computer resource controlled by the intermediary is being used to commit the unlawful act, the intermediary fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to that material on that resource without vitiating the evidence in any manner.

Explanation.—For the purpose of this section, the expression “third party information” means any information dealt with by an intermediary in his capacity as an intermediary.

[79] Aditya Gupta, The Scope of Online Service Providers' Liability for Copyright Infringing Third Party Content under the Indian Laws- The Road Ahead, 15 J. I.P.R. 35, 38 (2010).

[80] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 2(c).

[81] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 3(a).

[82] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 79, cl. 3(a).

[83] Pritika Rai Advani, Intermediary Liability in India, XLVIII (50) EPW 120, 125 (Dec. 2013).*

2. Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules, 2011

The Central Government notified the Intermediary guidelines rules on 11 April, 2011, in exercise of the powers conferred by Section 87(2)(zg) read with Section 79(2) of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The most significant part of these rules is their definition of the term ‘due diligence’ as used within section 79(2) (c) of the IT Act.

The ‘due diligence’ obligations of intermediaries under the Intermediary Guidelines[84] include three broad categories of requirements that are relevant: (a) the publication of certain rules, policies and user agreements; (b) the obligation not to knowingly host, publish, or transmit infringing information; and (c) the obligation to take down infringing information upon receiving actual knowledge of it.

[84] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011, r. 3.

i. Publication of Rules, Policies, and Terms and Conditions

Intermediaries are required to publish rules and regulations, privacy policies, and user agreements,[85] which appears to be enforced through self-regulation.[86] The Intermediary Guidelines do, however, set out fairly detailed broad terms that need to be a part of the intermediaries’ private agreement with users. The user agreements, rules, and policies must forbid the user from hosting, publishing, displaying, transmitting, or sharing any information[87]:

- That is grossly harmful, harassing, blasphemous, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, pedophilic, libelous, invasive of another's privacy, hateful or racially, ethnically objectionable, disparaging, or relating to or encouraging money laundering or gambling,

- Harms minors in any way;

- Impersonates another person;

- Belongs to another person and to which the user does not have any right;

- Infringes any patent, trademark, copyright, or other proprietary rights;

- Violates any law, among other things; or,

- Threatens the unity, integrity, defense, security, or sovereignty of India, friendly relations with foreign states, or a public order, or causes incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence or prevents investigation of any offence or is insulting to any other nation.

[85] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011, r. 3, cl. 1.

[86] John Braithwaite, Enforced Self-Regulation: A New Strategy for Corporate Crime Control,80(7) Mich. L. Rev. 1466 (1982).

[87] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011, r. 3, cl. 2.

ii. Hosting, publishing, transmitting, or modifying infringing information

The intermediary is also required to refrain from knowingly hosting, publishing, transmitting, or modifying any information prohibited under Rule 3(2)[88] (as listed in ‘a’ above).

Concerns were raised about the ambiguity of these terms, since none of them are defined in the IT Act or in the Intermediary Guidelines. In response, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Subordinate legislation has already asked the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology to incorporate definitions of all these terms within the Intermediary Guidelines, and to ensure that the Guidelines do not end up creating any new category of offence. [89]

[88] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011, r. 3, , cl. 3.

[89] Standing Committee on Subordinate Legislation, Thirty First Report on The Information Technology Rules (March 21, 2013), ¶ 25-26, available at http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/IT%20Rules/IT%20Rules%20Subordinate%20committee%20Report.pdf.

iii. Disabling Prohibited Information Upon ‘Actual Knowledge’

The intermediary, upon receiving actual knowledge, whether on its own or whether through a written communication from an affected person that infringing information is being stored, hosted, or published on its computer system, is obligated to ‘disable’ such information within 36 hours of obtaining such knowledge.[90] This last requirement effectively creates a notice and takedown regime. Although the Ministry insists that this is a self-regulatory regime[91], a study conducted by the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore has demonstrated that intermediaries over-comply and tend to take down even legitimate information when they are sent a notice.[92]

The Ministry of Communication and Information Technology argued before the Parliamentary Standing Committee that the requirement to ‘act’ within 36 hours means that intermediaries have to respond to and acknowledge the complaint within 36 hours of receiving it, and initiate appropriate action. Upon the Parliamentary committee’s insistence that this position should be clarified in the rules, the ministry issued an official clarification that states this position. [93] It said that while the Grievance Officer acting on behalf of the intermediary must act on the complaint expeditiously, the maximum time for redress is one month from the date on which the complaint was received, in accordance with Rule 3(11).

Subsequently, on 23 March 2012, a motion to annul guidelines was moved in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the Parliament). The annulment was defeated.[94] However, the rules have been challenged before the Supreme Court of India.

[90] The Information Technology (Intermediaries guidelines) Rules, 2011, r. 3, cl. 4.

[91] Standing Committee on Subordinate Legislation, Thirty First Report on The Information Technology Rules (March 21, 2013), ¶ 49, 55, available at http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/IT%20Rules/IT%20Rules%20Subordinate%20committee%20Report.pdf.

[92] RishabhDara, Intermediary Liability in India: Chilling Effects on Free Expression on the Internet, Centre for Internet & Society (Apr. 10, 2012), available at http://cis-india.org/Internet-governance/intermediary-liability-in-india.

[93] Department of Electronics and Information Technology, Ministry of Communications & Information Technology, Government of India, Clarification on The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2011 under section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (Msarch 18, 2013), available at http://deity.gov.in/sites/upload_files/dit/files/Clarification%2079rules(1).pdf.

[94] AnupamSaxena, Motion For Annulment of India’s IT Rules Defeated In RajyaSabha; IT Minister Promises Consultation, Medianama (May 18, 2012), http://www.medianama.com/2012/05/223-motion-for-annulment-of-india%E2%80%99s-it-rules-defeated-in-rajya-sabha-it-minister-promises-consultation/.

3. Blocking Orders Under the IT Act

Section 69A of the IT Act empowers the Central Government to direct the blocking of access to online information, and the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009 contain the procedure to be followed[95] for blocking access to information. As will be apparent from reading the procedure below, there are few external checks and balances in this process: the different stages of review of blocking orders are all conducted by committees or individuals who are a part of the executive branch of the government, and since there is a prohibition on disseminating information about the blocking orders[96], the entire process is very opaque.

These blocking orders may be directed at any government agency or intermediary. Although these orders can, in theory, be directed at any intermediary (including ISPs and online intermediaries), sources tell us that they are typically directed at telecommunication companies and ISPs. However, this is not exclusively so, since it appears that the government has issued section 69A blocking orders to online intermediaries.[97]

The language used in the IT Act does not permit blocking orders to be issued arbitrarily. Under section 69A, it is only when the Government is of the view that it is “necessary or expedient” so to do in the interest of “sovereignty and integrity of India, defense of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence relating to above”[98], that it can direct blocking access to information generated, transmitted, received, stored, or hosted in any computer resource.[99]

The reasons for the blocking must be recorded in writing.[100] Intermediaries who do not comply with the requests can be punished with imprisonment of up to seven years and are also liable to pay a fine.[101]

Individuals cannot directly request the blocking of access to any content[102] and need to send their complaints to the 'nodal officers' of the organizations in question.[103] The term ‘organizations’ in India means ministries and departments of the Central Government, or any of the State, Union Territory, or other Central Government agency that may be notified.[104]After examining the complaint and being satisfied h the need to block access, the organization may forward the complaint through its nodal officer to the 'Designated officer',[105] who is appointed by the Central Government and is the only person under the act who can issue directions for blocking (apart from the courts).

All the requests received by the Designated Officer are to be examined by a committee[106] (referred to as ‘Blocking Order Committee’ in this paper) consisting of the designated officer and representatives from the ministries of Law and Justice, Home Affairs, Information and Broadcasting, and the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In)[107] within seven days[108]. The committee is required to examine the request and determine whether it is covered under the grounds mentioned in Section 69A and should give specific recommendations on the request received.[109] The designated officer is required to make an effort to identify the person to whom the information in the complaint belongs or the intermediary who has hosted the information, and give this individual or entity the opportunity to be heard.[110] The recommendations of the Blocking Order Committee are presented to the Secretary of the Department of Technology for approval.[111] This process may be bypassed in the event of an emergency, in which case the designated officer is authorized to examine the request and submit his recommendations to the Secretary[112], who, if satisfied, can pass an interim decision to block access through a written and reasoned order.[113] However, this request has to be brought before the Blocking Order Committee within 48 hours of the blocking order by the Secretary[114] and on the basis of the recommendations of the committee, the Secretary may revoke his/her approval and ask for the blocked content to be unblocked.[115] It is important to note that by the time blocking orders come before the Review Committee, the content under question is already blocked in India. This raises questions about how the committee is able to view the actual content, which may include videos, blocked during its review.

The rules also provide separately for a Review Committee[116], which is mandated to meet at least once in every two months to review whether the directions issued for blocking are in accordance with Section 69A(1).[117] If the Review Committee is of the opinion that the orders issued are not in conformity with Section 69A(1), it may set aside the blocking order and ask for the information to be unblocked.[118] It is important to note that by the time blocking orders come before the Review Committee, the content under question is already blocked in India. This raises questions about how the committee is able to view the actual content, which may include videos, blocked during its review.

The Review Committee for blocking orders does not have to review orders from Indian courts asking for the blocking of any information. In these situations, the designated officer is required to submit a certified copy of the court order to the Secretary and initiate action as directed by the court.[119]

[95] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69A, cl. 2.

[96] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 16; Verizon Releases Transparency Report (Jan, 22, 2014), http://newscenter.verizon.com/corporate/news-articles/2014/01-22-verizon-releases-transparency-report/.

[97] http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/psearch/QResult15.aspx?qref=151935.

[98] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69A, cl. 1.

[99] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69A, cl. 1.

[100] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69A, cl. 1.

[101] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69A, cl. 3.

[102] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 6.

[103] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 4.

[104] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 2, cl. g. “Organisation” means – (i) Ministries/Departments of Government of India; (ii) State Governments and Union Territories; (iii) Any other entity as may be notified in Official Gazette by the Central Government.

[105] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 3.

[106] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 7.

[107] Constituted under the Information Technology Act, 2000, § 70B.

[108] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 11.

[109] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 8.

[110] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 8, cl. 1, cl. 2 and cl. 3.

[111] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 8, cl. 5 and cl. 6.

[112] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 9, cl. 1.

[113] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 9, cl. 2.

[114] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 9, cl. 3.

[115] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 9, cl. 4.

[116] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 2, cl. (i) read with the Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951, r. 419A.

[117] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 14.

[118] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 14.

[119] The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, r. 10.

4. Interception Under the IT Act

Section 69 of the Information Technology Act requires intermediaries to extend all facilities and technical assistance to intercept, monitor or decrypt information, provide information stored in a computer or provide access to a computer resource, when called upon to do so by the agency of the appropriate government as contemplated in Section 69. This clearly extends to online intermediaries. As stated above, intermediaries that fail to meet these obligations may be punished with imprisonment of up to seven years.[120]

The power to order interception rests with both the Central Government and the State Governments. Officers specially authorized have the power to order interception, monitoring, or decryption of data under specified circumstances. An interception order can be passed if it is necessary or expedient to do so in the interest of sovereignty or integrity of India, the defense of India, the security of State, friendly relations with foreign states, a public order, for preventing incitement to the commission of a cognizable offence relating to the above, or for investigation of any offence.[121] Interception of online communication is subject to the Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, and has to follow the process detailed in the legislation.

The order for interception must be issued by a competent authority[122] designated as the Secretary in charge of the Ministry of Home Affairs for Central Government,[123] or the Home department for States or Union Territories[124] as may be applicable. The competent authority is required to consider whether it is possible to acquire the necessary information by other means and to order interception only if this is not possible.[125]An interception order may only remain in force for up to a period of 60 days and cannot be extended beyond a total of 180 days.[126]

Interception orders are conveyed to intermediaries by a designated nodal officer who authenticates them and conveys them to the designated person within the intermediary[127] along with a written request to facilitate the interception.[128] The designated officer of the intermediary or person in charge[129] must acknowledge the interception order within two hours of receipt and has to facilitate interception.[130] Intermediaries need to send interception requests every 15 days for authentication to the nodal officer of government agency.[131]

Intermediaries are required to destroy all the records within a period of two months following the discontinuance of interception or monitoring, unless they are required for any ongoing investigation, criminal complaint, or legal proceedings.[132]

Section 69B of the IT Act empowers the Central Government to authorize a government agency to monitor and collect attributes of the content, such as the time and date of its sending, size, duration, route (including the location and identities of the points of origin and destination),[133] and the type of underlying service (‘traffic data’) in order to enhance cyber security or for identification analysis and the prevention of intrusion or spread of computer containment in India.[134] Intermediaries are obligated to provide technical assistance and extend all facilities to the authorized agency,[135] or risk imprisonment for up to seven years.[136] These detailed procedures and other safeguards for such orders are listed in the Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Monitoring and Collecting Traffic Data or Information) Rules 2009.

Like the Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, these rules require an order from a competent authority. This order may however be issued for a range of cyber security purposes including, tracking cyber security breaches or incidents, identifying or tracking any person who has breached, or who is suspected of having breached or being likely to breach, cyber security[137], and must contain the reasons issuing such direction.[138] A nodal officer has to receive the order and send it to the designated officer of the intermediary.[139] These safeguards are very similar to the safeguards outlined above for interception of information.

These rules also place obligations on the intermediary or the person in charge to put in place adequate checks to ensure that unauthorized monitoring does not take place[140] and make the intermediary liable for the actions of its employees in the case of unauthorized monitoring or the collection of data[141].

[120] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69, cl. 4.

[121] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69, cl. 1.

[122] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 3.

[123] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 2(d)(i).

[124] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 2(d)(ii).

[125] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 8.

[126] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 11.

[127] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 12.

[128] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 13.

[129] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 14.

[130] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 15.

[131] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 18.

[132] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, r. 23(2).

[133] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69B, explanation (ii) .

[134] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69B, cl. 1.

[135] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69B, cl. 2.

[136] The Information Technology Act, 2000, § 69B, cl. 4.

[137] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, r. 3(2).

[138] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, r. 3(3).

[139] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, r. 4(2).

[140] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, r. 5.

[141] The Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules 2009, r. 6.

C. The Copyright Act, 1957

The safe harbor protection provided to intermediaries under the IT Act is subject to section 81 of the IT Act which states that nothing contained in the IT Act shall restrict any person from exercising any right conferred under the Copyright Act.[142] If not for the safe harbor protection contained within the Copyright Act, intermediaries could be held liable under Section 51(a)(ii) for secondary copyright infringement: under this, any person who provides any place to be used for communication of work to the public for profit, where such communication constitutes a copyright infringement, may be held liable for the infringement.[143] This would ordinarily open intermediaries to liability in cases where they store information on their servers and/or transmit it onwards, particularly when the profit from advertising in relation to infringing content.[144]

However, a safe harbor has been included via section 52 of the Copyright Act, which states that “transient or incidental storage of a work or performance purely in the technical process of electronic transmission or communication to the public” shall not amount to copyright infringement; and that “transient or incidental storage of a work or performance for the purpose of providing electronic links, access or integration, where such links, access or integration has not been expressly prohibited by the right holder” is also not infringement, unless the intermediary has reasonable grounds for believing that such storage is of an infringing copy. It has been made clear that the immunity offered under section 52 is not meant to extend to deliberate storage of infringing information.[145] However the problem here is the interpretation of what amounts to reasonable grounds for belief that an intermediary is storing infringing content; the judiciary has, in the past, seen the insertion of algorithm-generated advertisements as an indication of knowledge of infringement[146]. Commentators point out that this standard will need to be discarded since it confuses physical space with the manner in which the Internet works.[147]

Like the IT Act, the Copyright Act makes its immunity for intermediaries conditional: the proviso to Section 52(1)(c) requires intermediaries to refrain from facilitating access to potentially infringing content for 21 days upon receiving a written complaint from the copyright owner about infringement that is taking place the transient or incidental storage that constitutes infringement. However, access to the content may be restored after 21 days unless a court order requiring the take down is received within a period of 21 days. This creates a notice and takedown regime where content needs to be removed at the behest of individual complaints. Unlike the IT Act, however, the Copyright Act explicitly authorizes the restoration of content in cases where a court has not endorsed the complaint.

This notice and takedown regime is mapped out more clearly in Rule 75 of the Copyright Rules of 2013. The rights holder has to give written notice[148] to the intermediary, including details about the description of work for identification,[149] proof of ownership of original work,[150] proof of infringement by work sought to be removed,[151], the location of the work[152] (which would be the specific URL), and details of the person who is responsible for uploading the potentially infringing work (if available).[153] Upon receiving such a notice, the intermediary has to disable access to such content within 36 hours.[154] In a departure from the Intermediaries Guidelines, and in a positive move for transparency, intermediaries that host content are required to display reasons for disabling access to anyone trying to access the content.[155] The intermediary is permitted, but not required, to restore the content after 21 days if no court order is received to endorse its removal.[156] It is then not required to respond to further notices from the same complainant about the same content at the same location.[157]

However, the regime under the Copyright Act is also not without its problems. Critics have objected to the narrowness, “transient or incidental storage”, which is necessary to claim immunity from liability under the safe harbor provision. They have also objected to the process under Rule 75, pointing out that it should have required the intermediary to notify the person who uploaded or created the content, creating an opportunity for a response that will enable the intermediary to let the content remain as is.[158]

Also of concern are the vaguely worded court orders increasingly issued in the context of copyright issues. These “John Doe” orders – or “Ashok Kumar” orders as they are called in India – are used by copyright owners to get ex parte injunctions against unknown parties.[159] There was a point at which these orders were so broad that they could be interpreted as creating a positive obligation on all intermediaries to proactively remove the questionable content. An example of the language used is, “For the forgoing reasons, defendants, their partners, proprietors…servants, agents, representatives…other unnamed and undisclosed persons, are restrained from communicating without license or displaying, releasing, showing, uploading, downloading, exhibiting, playing, and/or defraying the movie "DEPARTMENT" in any manner without a proper license from the plaintiff”.[160]

The Madras High Court in M/s. R.K. Productions Pvt. Ltd. vs. Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited & 19 others,[161] clarified in June 2012 that an earlier interim injunction was granted only in relation to a particular URL where the infringing movie is hosted, and not to of the entire website (addressing the overbroad blocking that was taking place by ISPs in response to such injunctions). Further, the applicant is directed to inform the respondents/defendants about the particulars of URL where the infringing movie is kept. On such receipt of the particulars of the URL in question from the plaintiff/applicant, the defendants shall take necessary steps to block such URLs within 48 hours. The following year, in December 2013, the Delhi High Court passed an Ashok Kumar order, an ad interim ex parte injunction that applied to “unnamed and undisclosed persons” in relation to the display, duplication, and distribution of the film ‘Dhoom 3’.[162] Recently, the Delhi High Court issued such an injunction prohibiting 472 websites[163] and other unknown ones from broadcasting 2014 FIFA World Cup matches, which it then reduced to a list of 219 upon an objection that several of the websites on the list did not belong there.[164]

[142] This position is affirmed by Super Cassettes Industries Ltd v. Myspace Inc, M.I.P.R. 2011 (2) 303 (India).

[143] The Copyright Act, 1957, § 51, cl. a(ii).

[144] Super Cassettes Industries Ltd v. Myspace Inc, M.I.P.R. 2011 (2) 303 (India); Aditya Gupta, The Scope of Online Service Providers' Liability for Copyright Infringing Third Party Content under the Indian Laws- The Road Ahead, 15 J. I.P.R. 35, 37 (2010).

[145] Ananth Padmanabhan, Give Me My Space and Take Down His, 9 I.J.L.T 2 (2013), available at http://www.ijlt.in/archive/volume9/Ananth%20Padmanabhan.pdf.

[146] Super Cassettes Industries Ltd v. Myspace Inc, M.I.P.R. 2011 (2) 303 (India).

[147] Ananth Padmanabhan, Give Me My Space and Take Down His, 9 I.J.L.T 15-16 (2013), available at http://www.ijlt.in/archive/volume9/Ananth%20Padmanabhan.pdf.

[148] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2.

[149] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2(a).

[150] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2(b).

[151] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2(c).

[152] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2(d).

[153] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 2(e).

[154] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 3.

[155] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 4.

[156] The Copyright Act, 1957, § 52(1), proviso.

[157] The Copyright Rules, 2013, r. 75, cl. 6.

[158] Apar Gupta, Copyright Rules, 2013 and Internet Intermediaries, Indian Law and Technology Blog (March 22, 2013); http://www.iltb.net/2013/03/copyright-rules-2013-and-Internet-intermediaries/; Chaitanya Ramachandran, A Look at the New Notice and Takedown Regime under the Copyright Rules 2013, Spicy IP (Apr 29, 2013), http://spicyip.com/2013/04/guest-post-look-at-new-notice-and.html.

[159] Lawrence Liang, Meet Ashok Kumar the John Doe of India; or The Pirate Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, Kafila (May 18, 2012), http://kafila.org/2012/05/18/meet-ashok-kumar-the-john-doe-of-india-or-the-pirate-autobiography-of-an-unknown-indian/.

[160] Viacom 18 Motion Pictures v. Jyoti Cable Network and Ors, C.S.(OS) 1373/2012 (May 14, 2012), High Court of Delhi (India).

[161] M/s. R.K. Productions Pvt. Ltd. v. Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited & 19 Others, C.S. (OS) 208/ 2012 (June 22, 2012), The High Court of Judicature at Madras (India).

[162] Yash Raj Films Pvt Ltd v. Cable Operators Federation of India and Ors, C.S.(OS) 2335/2013 (Dec. 2, 2013), High Court of Delhi (India).

[163] Multi Screen Media Pvt Ltd v. Sunit Singh and Ors, CS(OS) 1860/2014 (June 23, 2014), High Court of Delhi (India).

[164] Nikhil Pahwa, World Cup 2014: 219 websites blocked in India, after Sony complaint, Medianama (Jul 7, 2014), http://www.medianama.com/2014/07/223-world-cup-2014-472-websites-including-google-docs-blocked-in-india-following-sony-complaint/.

III. Impact Assessment

The legal framework governing the liability of Internet intermediaries in India has to remain consistent with the Indian Constitution.[165] This means that the statutory framework under which intermediaries are liable to block, take down, intercept, and monitor content may be challenged if it violates the right to the freedom of speech and expression,[166] or the right to privacy (as read into the right to life and personal liberty,[167] the right to the freedom of speech, and expression by the judiciary[168]) granted by the Constitution. The regulatory framework is also subject to administrative law principles, derived largely from common law; meaning rules, notifications, and actions arising from legislations must remain within the scope of their parent statute and the constitution[169] and cannot usurp any function that rightfully belongs to the legislature.[170]

The technology actually used by intermediaries has had visible effects on speech,[171] and has resulted in over-blocking in the past. It does, however, appear that regulators take into account market concerns — these concerns are increasingly reflected in reports that discuss the formulation of the regulatory regime and in arguments made by the Government of India before the Supreme Court of India.[172]

The narrative in the earlier parts of this paper maps out the different kinds of liability to which online intermediaries are subject in India. This includes criminal liability for several kinds of content, including content that is defamatory,[173] obscene,[174] or amounts to contempt of court.[175] The Indian Penal Code uses gatekeeper liability to regulate unlawful speech[176], and this can make operations risky for intermediaries without immunity from liability under section 79 of the IT Act. Recent interpretations of the law by the Indian Supreme Court indicate that intermediaries may find themselves at risk despite the immunity offered by the IT Act. In January 2015, the Supreme Court passed an interim order in an ongoing case, requiring Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft to refrain from advertising or sponsoring any advertisement which would violate Section 22 of the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994.[177] This interpretation seems to accept the argument made by the Ministry of Information and Communications that search engines, as intermediaries under the IT Act, owing to their ‘due diligence’ obligations, must block all content that breaches Indian laws. However since this is merely an interim order, there remains some chance that the Supreme Court will change its mind on the subject by the time the final judgment is delivered.

If the interim order represents the Supreme Court’s stand on this subject, it may undo the beneficial effects of safe harbor protection for search engines. Intermediaries may have very little clarity about the kinds of content they need to weed out, given the different kinds of speech criminalized by multiple Indian statutes (indicative list in the table in Annexure 1). This makes intermediaries who exercise editorial control particularly vulnerable. The IT Act adds to the list of criminalized speech, creating new categories of offences punishable with imprisonment (‘grossly offensive’ information,[178] for example).

Online intermediaries with no editorial control are also in a precarious position, despite their greater access to immunity from liability. The safe harbor protection granted to them under the IT Act is conditional upon the intermediaries observing ‘due diligence’,[179] and on their removing unlawful content upon receiving ‘actual knowledge’ of such content.[180] Interestingly, one outcome of section 79 has been that online intermediaries are immune from liability in contexts in which bookstores, traditional media, and publishing houses would have been found to be liable (such as hosting obscene content).[181] Even online intermediaries with immunity are required to refrain from knowingly hosting, publishing, transmitting, or modifying any information prohibited under Rule 3(2).[182] This list of prohibited information consists of a very wide range of content including content that is ‘grossly harmful’, ‘harassing’, ‘pornographic’, ‘pedophilic’, ‘libelous’, ‘invasive of another's privacy’, ‘hateful’, ‘racially, ethnically objectionable’, and ‘disparaging’.[183] Many of these are categories of content that are not defined in Indian law at all.

Terms like ‘defamatory’ and ‘obscene’,[184] which are actually defined in other pieces of Indian legislation, are not defined in the Intermediary Guidelines. While this might not be a hardship for large online intermediaries like Google or Facebook that have the resources to hire a legal team, a start-up or small online intermediary may struggle to acquire the legal expertise to ascertain what is meant by all the terms listed in Rule 3. This makes Rule 3 an opaque and inaccessible rule from the intermediaries’ perspective. Compliance with such an unclear standard is difficult. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on subordinate legislation has recommended that all these terms which are not defined in the IT Act be defined in the Intermediary Guidelines for the convenience of the intermediaries and the general public.[185]If this recommendation were executed, it would make for a more transparent rule.

Intermediaries that are subject to the licensing system in India have to contend with the added burden of onerous requirements that cover blocking, interception, and monitoring.