Roles and Liabilities of Online Intermediaries in Vietnam – Regulations in the Mixture of Hope and Fear

This essay studies the policy and regulatory framework affecting the liability of online intermediaries in Vietnam by exploring how the liability of online intermediaries is shaped by the local authority’s ideology, concerns, and hopes, as well as other political and economic factors regarding the information, communications, and technology sector.

Roles and Liabilities of Online Intermediaries in Vietnam

Author: Thuy Nguyen[1]

Abstract: This essay studies the policy and regulatory framework affecting the liability of online intermediaries in Vietnam. Through this essay, readers will explore how the liability of online intermediaries is shaped by the local authority’s ideology, concerns, and hopes, as well as other political and economic factors regarding the information, communications, and technology sector. Maximizing local regulatory sovereignty over all types of Internet activities is the dominant feature of the current Vietnamese policy and regulatory landscape. This happens through various regulatory tools: server localization requirements, compulsory licensing or registration with the local government, required authentication of users’ identification, and extensive reporting obligations, among others. At the same time, there is also an image of Vietnam as strongly desiring to grasp the opportunities brought by the online environment in order to boost domestic economic development. This desire is mixed with the protectionist effort, which aims to promote locally branded online goods and services, favor homegrown online intermediaries, and capture domestically a larger portion of the income generated inside Vietnam by foreign businesses. A close look at the Facebook blocking case will illustrate this particular situation. Finally, to complete the picture of the Vietnamese regulatory and policy landscape, this essay also discusses the local regulatory attempts regarding the responsibilities of online intermediaries in protecting national security, data privacy, and network security.

[1] Thuy Nguyen is now an associate at Baker & McKenzie, Wong & Leow, practicing telecommunications, media, technology, and international trade law. She wrote this chapter when she was an LL.M candidate at Harvard Law School and an intern at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. All translations appearing within this essay are considered unofficial and prepared by the author for the ease of the reader’s reference, unless otherwise noted.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Analysis

A. Regulations Responding to Fears

1. Untested Internet in 1990s– Maximize Government Control Over Online Activities

2. Fear of Uncontrollable Content - Heavy Censorship

i. Exclusive “Mouthpiece” - Challenges on Censorship in the Internet Era & the Call for Censorship Innovations

ii. More censorship on Internet chokepoints

iii. Censorship and International Trade Law Constraints

3. Traditional Fears

i. National Security Risks

ii. Online Frauds

iii. Data Privacy Protection Concerns

iv. Network Safety – Malwares & virus

4. The Fear of the Failure to Localize the Benefit of Online Services – Domestic Call

III. Regulations Reflecting Hopes

1. Embracing New Opportunities for Economic Growth

i. Decree No. 55 and Its Subsequent Replacements - Doors Opened for Online Intermediaries

ii. IT Law – Promoting IT Development and Application

iii. Joint Circular No. 07 – Online Intermediaries’ Liabilities in Copyrights Protection

2. Turning Vietnam Into a Nation With a Strong IT Industry and With a Knowledge-Based Economy

i. Online Intermediaries as Supporters of Business Development

ii. Opportunities Brought by E-Commerce

iii. Booming of Internet Activities

III. Conclusion

I. Introduction

Vietnam seems to possess a notorious record regarding its treatment of the Internet. The organization Reporters without Borders refers to the country as one of the “enemies of the Internet.”[2] The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation names Vietnam as the author of one of the “10 worst innovation mercantilist policies of 2013.”[3] The country also has a record of suppressing online dissidents.[4] However, there is also another Vietnam that is less known internationally − one with the ambition of becoming an information economy, with information technology as the “focal industry” for economic growth. Recent legal and policy developments regarding online intermediaries in Vietnam reflect both of these images.

This essay focuses on analyzing the fears and hopes related to online activities, and the corresponding policies and regulations by the Vietnamese authorities. Relevant cases, regulations, and draft regulations will be analyzed to illustrate the roles and liabilities of online intermediaries.

Online activities bring both hope and fear to the current regime. Since the early 1990s, fear of the Internet as an untested technology that might affect the integrity of the current regime has led to regulations that allow the Vietnamese authorities to exercise heavy censorship and maximum controlling power over online activities. One of the regulatory tools used then was requiring all entities wishing to connect to the Internet to locate their servers in Vietnam and to connect to the Internet through a limited number of government-licensed international gateways. Furthermore, setting limits for what was admissible online content and what must be removed was crucial for maintaining the current regime. This control was deemed particularly important in the context that online platforms could be used to easily gather or organize anti-government forces. This set of fears resulted in heavy burdens for online intermediaries. For instance, in order to fully control local online activities, the government recently required online social network service suppliers to ensure that their users supply accurate personal information. Related, a national online identification database, which is under construction, will be used to verify personal information of online social network users.

In conjunction with the increasing popularity of the Internet in the country, Vietnam also gradually enacted regulations to address the traditional fears felt by other nations, including those concerning national security, fraud prevention, data and privacy protection, and network security. Some of the measures put into place in Vietnam are similar to those adopted in some other jurisdictions following the NSA revelation incident. Other measures addressed specific concerns regarding recent online frauds and security risks in Vietnam.

Moreover, the fear of the consequences of inadequate control, and a perceived need to localize the benefits of online services, has recently resulted in regulations and proposed regulations that exhibit a protectionist tendency for the domestic service suppliers, which involves the use of some regulatory tools similar to those used in the 1990s. In particular, some recently adopted regulations require the localization of servers as one of the conditions for the provision of certain online services in Vietnam. The blocking of Facebook, which has been in place since 2009, will be analyzed in detail to reveal its potential protectionist motivations. The essay will also explain how the “Vietnamese people prefer Vietnamese products” campaign affects the liabilities of online intermediaries. At the same time, Vietnam’s government sees the benefits of developing a strong domestic information technology industry, attracting high tech foreign investment, training a tech-savvy generation, boosting e-commerce, enforcing intellectual property protection, creating clear and transparent rules for e-commerce, and using online social networks to promote local businesses. Some major regulations will be analyzed to demonstrate this contrary perspective of the Vietnamese government towards online intermediaries.

Going forward, online intermediaries will likely experience strong opportunities to grow in Vietnam. However, they might have to shoulder heavy burdens to address the government’s specific fears. In particular, online intermediaries might face the choice of either cooperating with the local authorities to address relevant fears, or exiting the market. Though the liability of offshore online intermediaries that provide services to Vietnamese users on a cross-border basis currently remains ambiguous in certain cases, the same trend may soon apply to those intermediaries as well. However, in contrast to this trend toward heavy regulation, the specific commitments of Vietnam under applicable international trade arrangements may, to a certain extent, restrain Vietnamese discriminatory regulatory measures towards foreign online intermediaries.

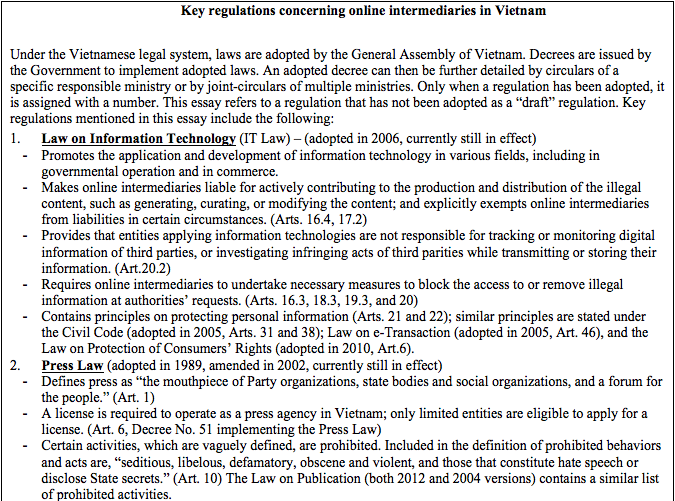

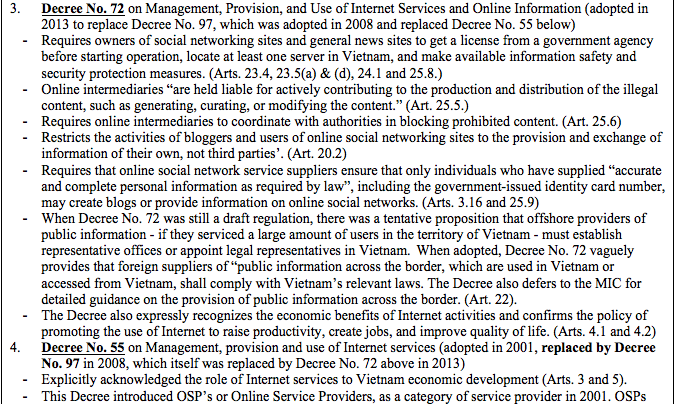

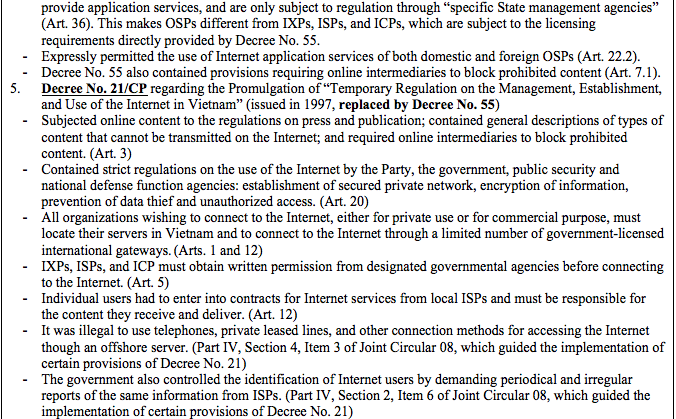

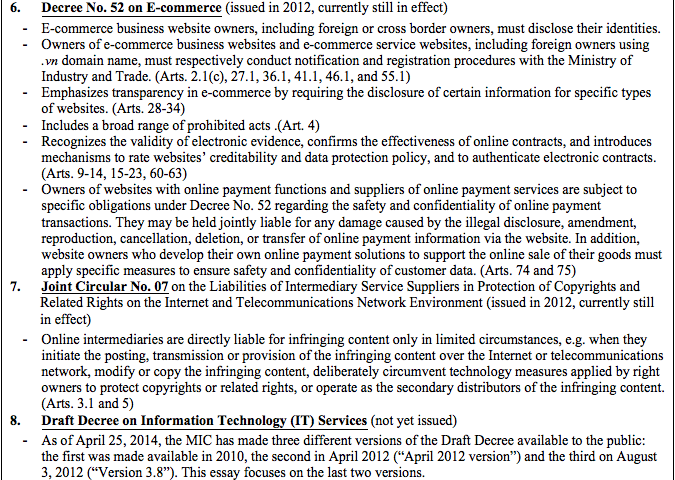

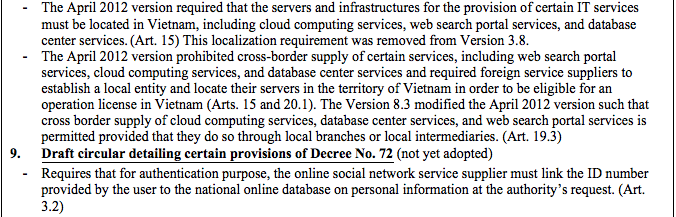

For the readers’ ease of reference - before going into detailed analysis - this essay provides a brief of key regulations concerning online intermediaries in Vietnam in Figure 1 and basic facts about the Internet in Vietnam in Figure 2 below.

Figure 1. Key regulations concerning online intermediaries in Vietnam

Figure 2. Basic facts about Internet in Vietnam

[2] See Reporters without Borders, Enemies of the Internet 2013 Report, March 12, 2013, available at http://surveillance.rsf.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/03/enemies-of-the-Internet_2013.pdf, accessed on February 28, 2014.

[3] See Michelle A. Wein and Stephen J. Ezell, The 10 Worst Innovation Mercantilist Policies of 2013, The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, January 2014, available at http://www.itif.org/pressrelease/ten-worst-innovation-mercantilist-policies-2013, accessed on February 28, 2014.

[4] See Human Rights Watch, Vietnam: Clinton Should Spotlight Internet Freedom, July 9, 2012, available at http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/09/vietnam-clinton-should-spotlight-Internet-freedom, accessed on March 3, 2014; See also Eva Galperin, Free Expression in Danger as Bloggers and Activists Go On Trial in Vietnam, Electronic Frontier Foundation, January 7, 2013, available at https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2013/01/bloggers-trial-vietnam-are-part-ongoing-crackdown-free-expression, accessed on February 10, 2014; See also Dara Kerr, Vietnam: Criticize Government on Social Media and Go to Jail, CNET, December 12, 2013, available at http://asia.cnet.com/vietnam-criticize-government-on-social-media-and-go-to-jail-62223058.htm, accessed on February 20, 2014; Committee to Protect Journalist, 2013 Prison Census - 211 Journalists Jailed Worldwide, as of December 1, 2013, available at http://www.cpj.org/imprisoned/2013.php, accessed on February 25, 2014.

II. Analysis

A. Regulations Responding to Fears

This section analyzes different sets of fears to illustrate their effect on the liabilities of online intermediaries in Vietnam. The country shares with other nations common fears regarding the Internet, including its possible effects on national security, online fraud prevention, data and privacy protection, and network security. However, the regime also demands specific regulations to address fears relating to uncontrollable content. Furthermore, Vietnam also worries about failing to capture domestically the financial benefits generated by foreign online intermediaries through their online activities in Vietnam. All of these fears result in a stringent liability regime for online intermediaries, the chokepoints of Internet activities.

1. Untested Internet in 1990s– Maximize Government Control Over Online Activities

Originally, the government’s concerns were related to the unprecedented nature of the Internet as a new technology, the benefits of which were untested in Vietnam. As a result, in the 1990s, regulations were of a cautious and exploratory nature, and Internet activities were permissible only to the extent that they were navigable and controllable by the government.

In particular, the domestic Internet architecture was designed in such a way that the local authority had full control over domestic online activities: all organizations wishing to connect to the Internet, either for private use or for commercial purposes, were required to locate their servers in Vietnam and to connect to the Internet through a limited number of government-licensed international gateways.[5]

Internet exchange providers (IXPs), Internet service providers (ISPs), private organizational Internet users, and Internet content providers (ICPs) had to obtain written permission from designated governmental agencies before connecting to the Internet.[6] Individual users had to enter into contracts for Internet services from local ISPs.[7] It was illegal to use telephones, private leased lines, and other connection methods for accessing the Internet though an offshore server.[8] The government also controlled the identification of Internet users by demanding periodical and irregular reports of the same information from ISPs.[9]

From the above structure, the government of Vietnam targeted IXPs, ISPs, private organizational Internet users, and ICPs as the chokepoints to control domestic Internet activities. This early model of heavy Internet control enabled the maximum local regulatory sovereignty, which, as discussed below, also closely resembles the current nature of Vietnamese Internet regulations.

[5] See Nghị định của Chính phủ số 21/cp ngày 5 tháng 3 năm 1997 về việc ban hành “Quy chế tạm thời về quản lý, thiết lập, sử dụng mạng Internet ở Việt Nam” [Decree No. 21/CP regarding the Promulgation of “Temporary Regulation on the Management, Establishment, and Use of the Internet in Vietnam,” issued by the Government of Vietnam on March 5, 1997], replaced by decree No. 55/2001/nd-cp in 2001, (Viet.) (hereinafter “Decree No. 21”), Art. 1.

[6] See Decree No. 21, Art. 5.

[7] See id., Art. 12.

[8] See Thông tư liên tịch Tổng Cục Bưu điện – Bộ Nội vụ - Bộ Văn hoá Thông tin số 08/TTLT ngày 24 tháng 5 năm 1997 Hướng dẫn Cấp phép việc Kết nối, Cung cấp và Sử dụng Internet ở Việt Nam [Joint Circular between the General Postal Department, Ministry of Internal Affairs, and Ministry of Culture and Information No. 08/TTLT dated May 24, 1997, Guiding the Licensing Procedures for the Connection, Provision and Use of the Internet in Vietnam], Part IV, Section 4, Item 3 (Viet.).

[9] See id., Part IV, Section 2, Item 6.

2. Fear of Uncontrollable Content - Heavy Censorship

The second set of fears relates to the ideology of the current Vietnamese regime. The Internet and the availability of online platforms enabled by various online intermediaries changed the nature of traditional journalism and content production in general: every user can easily generate content, the number of Internet users has increased immensely globally, creating a massive audience for online content, and the platforms hosting this content can be provided on a cross-border basis. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the Arab Spring, online platforms may serve as an effective means to mobilize social forces against the government. This is exactly the kind of risk in relation to online intermediaries that the current Vietnamese regime would like to prevent.[10] In such a context, controlling content – particularly that which conflicts with the communism ideology – at the user level is no longer the most efficient means. Thus, the local authority has turned its censorship focus to online intermediaries – the Internet chokepoints. This new focus has resulted in intensive obligations being imposed on online intermediaries. However, it appears that due to international trade law obligation constraints, among other things, some of the proposed requirements have not been adopted.

[10] Charlie Campbell, Internet Censorship is Taking Root in Southeast Asia, Time (Jul. 18, 2013), http://world.time.com/2013/07/18/Internet-censorship-is-taking-root-in-southeast-asia/#ixzz2uP36ZHbs.

i. Exclusive “Mouthpiece” - Challenges on Censorship in the Internet Era & the Call for Censorship Innovations

Unlike the press in the United States, which is treated as the “forth estate,” providing “a public check on the three classes of branches of government,”[11] the press in Vietnam is defined as the “mouthpiece of Party organizations, State bodies and social organizations, and a forum for the people.”[12] Accordingly, only Party organizations, State bodies, and social organizations are eligible for a license to establish a press agency in Vietnam.[13] Certain vaguely defined types of content are strictly prohibited, including those that are seditious, libelous, defamatory, obscene and violent, and those that constitute hate speech or disclose State secrets.[14] A similar set of content was also prohibited from publication and distribution, including electronic publication and distribution, according to the Law on Publication.[15]

The Internet, as observed by Yochai Benkler, changed the nature of traditional journalism.[16] Thanks to the reduction of production and distribution costs, every individual Internet user with basic computer skills can nowadays generate and proliferate content on the Internet in a matter of seconds. In fact, online social networking websites, such as Yahoo! 360 in the past and Facebook currently, are popular platforms for Vietnamese individuals to exchange online information and directly generate online content. They discuss political and economic topics, criticize governmental policies, spread the news, and gather to demonstrate against such policies, among other things.[17] Some of these activities were treated as libelous and seditious, and in violation of Vietnamese laws.

For example, in 2013, at least 46 bloggers or democracy activists were convicted and imprisoned on national security charges.[18] In particular, a Facebook user was sentenced to 15 months of house arrest for posting and exchanging false and distorting information, and harming the Government’s reputation, as well as the legitimate rights of organizations and citizens in October 2013.[19]

Since the introduction of the Internet in Vietnam, the government has insisted that all Internet users must be responsible for the content they deliver and receive online.[20] The law also consistently requires IXPs, ISPs, online service providers (OSPs), ICPs, and Internet service agents to act as gatekeepers in adopting appropriate measures to block the prohibited content defined under the Press Law and the Publication Law, among others.[21] However, a number of challenges have emerged over time, demanding regulatory innovations by the Vietnamese Government.

The first challenge involved the immense increase in the number of Internet users in Vietnam. By June 30, 2012, Vietnam already had 31 million Internet users, ranking within the top 10 countries in the Asia-Pacific Region in terms of Internet growth.[22] Although the Internet allows for the tracing of IP addresses, this tracing is not perfect. It is difficult to be certain of the real identity of an Internet user.[23] For example, Facebook users must be 13 years or older, and alcohol advertisement is prohibited for minors under 18 years old. Unlike the face-to-face communications outside the Internet world, there is currently no perfect mechanism to authenticate online whether the person acquiring the service for the first time is declaring his or her real age. Thus, illegal content may be available on the Internet beyond the government’s ability to regulate.

Secondly, many major online platforms are made available in Vietnam by foreign, rather than domestic, service suppliers. Since 2001, Vietnam has explicitly permitted the use of Internet application services of both domestic and foreign OSPs.[24] As a result, foreign-based services such as Facebook, Google’s search engine, and YouTube are among the most popular online tools for Vietnamese users. These services are supplied on a cross-border basis without establishing any local presence in Vietnam. This feature raises additional challenges to the Vietnamese regulator’s content control efforts. As a result, the government has demanded mechanisms to control online activities that take place not only via locally licensed online intermediaries, but also via popular offshore online intermediaries.

The Facebook blocking that began in 2009 represented one of the first responses against offshore online intermediaries who provide services on a cross-border basis in Vietnam. Although the government denied its involvement in the blocking, an unsigned official letter was circulated on the Internet bearing the instruction of a Department under the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security for ISPs.[25] Accordingly, ISPs were required to block a list of eight websites, including Facebook. Immediately following the date of that letter, Vietnamese users faced difficulties[26] accessing Facebook. With or without the government’s involvement, and regardless of the potential motivations behind this move (discussed further in the next section), this blocking was just the beginning of a much more systemic attempt to censor Internet content, signaling stricter burdens would be imposed on online intermediaries – the chokepoints in controlling online content. A series of regulations and draft regulations proposed since 2012 illustrate this attempt by the government of Vietnam, discussed below.

[11] "US vs Bradley Manning, Volume 17 July 10, 2013 Morning Session", Freedom of the Press Foundation: Transcripts from Bradley Manning's Trial, 29, July 10, 2013, https://pressfreedomfoundation.org/sites/default/files/07-10-13-AM-session.pdf.

[12] Luật Báo Chí [Press Law] adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on December 28, 1989, (Viet.) (hereinafter “Press Law”) Art. 1.

[13] Nghị định của Chính phủ số 51/2002/NĐ-CP ngày 26 tháng 4 năm 2002 Quy định chi tiết Thi hành Luật Báo chí, Luật sửa đổi, bổ sung một số điều của Luật Báo chí [Decree of the Government No. 51/2002/ND-CP dated April 26, 2002 Providing Detailed Guidance on the Implementation of the Press Law, the Law Amending Certain Provisions of the Press Law] (Viet.) (hereinafter Decree No. 51), Art. 6.

[14] See Press Law, Art. 10; See also Decree No. 51, Art. 5.

[15] Luật Xuất bản [Law on Publication] No. 19/2012/QH13, adopted by the National Assembly on November 20, 2012 (Viet.) (hereinafter “Publication Law”), Art. 10.1. The same languages were also included in previous version of the Publication Law such as Law No. 30/2004/QH11 dated December 3, 2004, Art. 10.

[16] Yochai Benkler, A free Irresponsible Press: Wikileaks and the Battle over the Soul of the Networked Fourth Estate, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Winter 2012, Vol. 47 Issue 1, 311, at 371-379.

[17] See H.C., Facebook in Vietnam - Defriended, The Economist (Jan. 4, 2011, 17:46), http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2011/01/facebook_vietnam.

[18] Vietnam Court Convicts Dissident Facebook User, Associated Press (Oct 29, 2013, 02:27:32), http://bigstory.ap.org/article/vietnam-court-convicts-dissident-facebook-user.

[19] The charge against this Facebook user was “abusing democracy and freedom rights, causing harms to the Government’s interest and the legitimate rights and interest of organizations [and] citizens.” His activities were the effort to overturn his brother’s conviction for anti-government propaganda. See Vietnamplus, Tuyên phạt 15 tháng tù treo đối tượng Dinh Nhật Uy [Sentencing 15 Months of House Arrest Against Dinh Nhat Uy], VTV, (Oct. 29, 2013, 22:12), http://vtv.vn/Thoi-su-trong-nuoc/Tuyen-phat-15-thang-tu-treo-doi-tuong-Dinh-Nhat-Uy/87378.vtv. See also Martin Petty and Robert Birsel, Vietnam Court Sentences Facebook Campaigner to House Arrest, Reuteurs (Oct. 29, 2013, 5:21 AM), http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/10/29/us-vietnam-court-idUSBRE99S0DP20131029.

[20] See Decree No. 21, Arts. 1 and 12.

[21] See Decree No. 21 Art. 3; Nghị định 55/2001/NĐ-CP ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2001 về Quản lý, Cung cấp và Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet [Decree No. 55/2001/ND-CP dated August 23, 2001 regarding the Management, Provision and Use of Internet Services], replaced by decree No. 97/2008/ND-CP IN 2008 (Viet.) (hereinafter “Decree No. 55”), Arts. 3.1 and 7.1; IT Law, Arts. 16.3, 18.3, 19.3, and 20; Nghị định của Chính phủ số 97/2008/NĐ-CP ngày 28 tháng 8 năm 2008 về Quản lý, Cung cấp, Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet và Thông tin Điện tử trên Internet [Decree No. 97/2008/ND-CP of the Government dated August 28, 2008 on Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Electronic Information on the Internet], replaced by decree No. 72/2013/nd-cp in 2013 (Viet.) (hereinafter “Decree No. 97”), Art. 10.2(c), 11.2(c), 21.1(c); Nghị định Quản lý, Cung cấp, Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet và Thông tin trên mạng [Decree on Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Online Information] No. 72/2013/ND-CP dated July 15, 2013 (Viet.) (hereinafter “Decree No. 72”), Art. 25.6.

[22] See National Steering Committee on ICT (NSCICT) and Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC), White Book 2013: Vietnam information and communication technology, Information and Communications Publishing House, (2013), at 22.

[23] For a comparison between identity authentication in the Internet and that in real space and for more discussion on the relationship between users’ identification and the “regulability” of the Internet, see Lessig, at 38-60.

[24] Decree No. 55, Art. 22.2.

[25] The letter is available on Wikileaks at this link: http://file.wikileaks.org/file/vietnam-banned-facebook.jpg (last visited April 10, 2014) (Viet.).

[26] Though there were some inconveniences in accessing Facebook following the alleged blocking, the blocking was easily circumvented by using certain proxy techniques. The access speed varied among ISPs and accession via mobile phones was not affected. Please see further discussion and explanation in the next section of the essay.

ii. More censorship on Internet chokepoints

In general, online intermediaries must remove or block access to the prohibited content that they self-detect or per the request of the competent authority in Vietnam.[27] They are held liable for actively contributing to the production and distribution of the illegal content, such as generating, curating, or modifying the content.[28]

Decree No. 72, adopted in July 2013,[29] in line with the traditional Vietnamese command and control regulatory model, requires owners of online social networking websites and general news websites[30] to obtain a license from the government agency before providing their services.[31] Notably, the licensee must satisfy certain conditions including, among other things, being established under Vietnam law,[32] and having at least one server located in the territory of Vietnam.[33] Similarly, under these regulations, publishers and distributors of electronic publications must also locate their servers in Vietnam.[34]

Furthermore, the April 2012 version of the Draft Decree on Information Technology Services[35] required that the servers and infrastructure for the provision of certain IT services be located in Vietnam. These services include cloud computing services, web search portal services, and database center services.[36] This approach to a certain extent reflects the regulatory approach that Vietnam originally applied in the 1990s – maximizing domestic control over online activities. In other words, the server localization, among others, allows Vietnam to effectively exercise its sovereignty over Internet activities in Vietnam.

The Vietnamese Government also adopted measures to limit user content sharing activities such that its regulatory scope can focus on the chokepoints − online intermediaries. In particular, Decree No. 72 restricts the activities of bloggers and users of online social networking sites to the provision and exchange of information of their own, not third parties’ information. Accordingly, permissible activities do not include “posting aggregated information.”[37] This provision seems to address the issue of content “curation”, as commonly referred to in other jurisdictions. In response to the accusation that this provision restricts freedom of speech, a representative of the Ministry of Information and Communications (“MIC”) called the accusation a “misunderstanding” and clarified that Vietnam “never bans people from sharing information or linking news from websites.”[38] Rather, the provision “was aimed at protecting intellectual property and copyright” [relating to the posting of aggregated information].[39] In an interview with VOV, MIC Deputy Minister called the accusation a “quibble,” and argued that the provision was actually helpful in guiding users as to the boundary of their online activities for their ease of compliance.[40]

Regardless of whether the above provision restricts freedom of speech, it has an important direct effect with respect to which sites or individuals are subject to regulation. Particularly, once a blogger or a user of online social networking sites posts aggregated information, their websites will likely be treated as a general news website, which are subject to the licensing requirement mentioned above. This licensing procedure serves both as a mechanism for the government to review and evaluate the capability of every applicant, and as a burden that discourages individual users from posting aggregated information. Since only licensed owners of general news websites can post aggregated information, the government does not have to extend their control over aggregated information content beyond this limited group of licensees (such as bloggers posting aggregated news on their blogs).

Furthermore, besides the traditional requirement for coordination from gatekeepers, the Government of Vietnam is currently attempting to take one step further to directly control users’ activities on online social networks. Specifically, Decree No. 72 requires that online social network service suppliers ensure that only individuals who have supplied “accurate and complete personal information as required by law,” including the government-issued identity card number, may create blogs or provide information on social networks.[41]

The draft circular implementing Decree No. 72 further requires that for authentication purposes, the supplier must link the ID number provided by the user to the national online database on personal information at the authority’s request.[42] The national online identification database is still a work in-progress, thus this requirement is not enforceable until the database is fully developed.[43] However, once implemented, this ID verification scheme will possibly make the Internet users’ behaviors more - in Lawrence Lessig’s words - “regulable”.[44] Verification will in theory prevent crimes, frauds, and defamation as well as promote trust on the online environment, which is good for e-commerce.[45]

Nevertheless, at the same time, the required disclosure of users’ real identity may effectively contribute to the suppression of freedom of speech.[46] For example, the awareness that speech can directly link to a real identity will hinder users from expressing anti-government and other controversial opinions, and may even discourage them from expressing opinion at all due to the risk of liabilities.

This choice of architecture reflects a value choice by the government. Obviously, freedom of speech is not the government’s priority in this case. Rather, online intermediaries’ compliance with this requirement will likely enable the government to regulate the Internet more effectively at the cost of freedom of speech.

So far, the liabilities of offshore online intermediaries that provide services to Vietnamese users on a cross-border[47] basis are still ambiguous. When Decree No. 72 was still a draft regulation, there was a tentative proposition that offshore providers of public information - if they serviced a large amount of users in the territory of Vietnam - must establish representative offices or appoint legal representatives in Vietnam.[48] Similarly, the April 2012 version of the Draft Decree on IT Services prohibits cross-border supply of certain services, including web search portal services, cloud computing services, and database center services.[49] Rather, in order to provide the relevant services in Vietnam, the foreign service suppliers must establish a local entity and locate their servers in the territory of Vietnam in order to be eligible for a license.[50] These proposed regulations, if adopted as such, would effectively extend Vietnamese local regulatory power to a broad range of otherwise cross-border Internet activities in Vietnam, similar to the state of affairs in the 1990s (as discussed above).

[27] See IT Law, Arts. 16.3, 18.3(b), 19.3 (regarding the liabilities of entities transmitting and disseminating digital information, leasing online storage, and providing digital information search tools); See also Decree No. 72, Arts. 24.4 and 25.6 (regarding obligations of general news websites and online social networking websites).

[28] See IT Law, Art. 16.4 (providing cases where entities transmitting and disseminating electronic information are liable for illegal information); Art. 17.2 (providing cases where entities are liable for the information they temporarily store); See also Decree No. 72, Art. 25.5.

[29] Nghị định Quản lý, Cung cấp, Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet và Thông tin trên mạng [Decree on Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Online Information] No. 72/2013/ND-CP dated July 15, 2013 (Viet.) (hereinafter “Decree No. 72”).

[30] “General news website” means websites that provides aggregated information about politics, economics, culture and/or society, on the basis of citing textually and accurately from official sources and specify the names of the authors or agencies of the official sources, and the time when such information is published. Decree No. 72, Arts. 3.19 and 20.2.

[31] Decree No. 72, Art. 23.4.

[32] See id. Art. 23.5(a).

[33] See id. Arts. 24.1 and 25.8.

[34] Nghị định Quy định Chi tiết Một số Điều và Biện pháp Thi hành Luật Xuất Bản [Decree Detailing Certain Provisions and the Implementation of the Law on Publication] No. 195/2013/ND-CP dated November 21, 2013, Art. 17.1(a).

[35] See Dự thảo Nghị định về Dịch vụ Công nghệ Thông tin [Draft Decree on Information Technology Services], Apr. 2012, available at http://qtsc.com.vn/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=63cd7c9e-065c-4f06-a6a0-93ab819b7ce2&groupId=18, (last visited Jan. 1, 2014) (Viet.), (hereinafter “April Version”).

[36] See April Version, Art. 15. The same requirements was removed from the latest publicly available version of this Draft Decree. See the collection of version 3.8 of the Draft Decree and a set of comments in both English and Vietnamese, http://www.vibonline.com.vn/Duthao/1250/Nghi-dinh-ve-dich-vu-cong-nghe-thong-tin.aspx, (last visited Jan. 1, 2014).

[37] Decree No. 72, Art. 20.2. “Aggregated information means information that is collected from multiple sources and types of information about politics, economics, culture and/or society.” Decree No. 72, Art. 3.19.

[38] Vietnam Rebuffs Criticism of ‘Misunderstood’ Web Decree, Reuters (Aug. 6, 2013, 7:53), http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/08/06/vietnam-Internet-idUSL4N0G72IA20130806.

[39] Id.

[40] Hương Giang, Nghị định 72 Không Hạn chế Quyền Tự do Ngôn luận [Decree No. 72 Does Not Restrict Freedom of Speech], VOV (Aug. 7, 2013, 16:41), http://vov.vn/Xa-hoi/Nghi-dinh-72-khong-han-che-quyen-tu-do-ngon-luan/274653.vov (VOV reporter interviewed the Deputy Minister of Information and Communications, Mr. Do Quy Doan, regarding the provision of Decree No. 72).

[41] Decree No. 72, Arts. 3.16 and 25.9.

[42] See Dự thảo Thông tư Quy định Chi tiết Một số Điều của Nghị định 72/2013/NĐ-CP Ngày 15 tháng 7 năm 2013 về Quản lý, Cung cấp, Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet và Thông tin Trên mạng Đối với Hoạt động quản lý trang thông tin điện tử và dịch vụ mạng xã hội [Draft Circular Detailing the implementation of Certain Provisions regardingManagement of General News Websites and Online Social Networking Services of Decree No. 72/2003/ND-CP dated July 15, 2013 on the Management, Provision and Use of Internet Services and Online Information], Art. 3.2(b), downloadable at http://mic.gov.vn/Attachment%20Lay%20Y%20Kien%20Nhan%20Dan/Du%20thao%20thong%20tu%20MXH%20(Du%20thao%203%20ngay%204.%209).doc (last visited April 25, 2014).

[43] Lê Mỹ, Chưa Bắt Doanh nghiệp Xác thực Chứng minh thư Thành viên Mạng Xã hội [Not Yet Requiring Enterprises to Verify the Identification of Online Social Network Users], ICTNews (Jan. 10, 2014, 16:52), http://ictnews.vn/Internet/chua-bat-doanh-nghiep-xac-thuc-chung-minh-thu-thanh-vien-mang-xa-hoi-114111.ict.

[44] Lawrence Lessig, Code is Law 2.0, at 16.

[45] Lessig found this crucial for e-commerce. However, the identification authentication that Lessig foresees as the “most important tool for identification in the next ten years” is far different from the proposed requirement of the Vietnamese government. He endorses the technology that can verify specific users’ information for specific online purposes; but the disclosure of users’ identities to the authorities requires warrant. See Lessig at 50-54.

[46] For a succinct summary of the importance of pseudonymity, see Mike Masnick, What's In A Name: The Importance Of Pseudonymity & The Dangers Of Requiring 'Real Names', TECHDIRT, (Aug. 5, 2011; 6:36 PM.)

https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20110805/14103715409/whats-name-importance-pseudonymity-dangers-requiring-real-names.shtml.

[47] The cross-border supply of a service occurs when the service supplier is not present within the territory of Vietnam but the service is delivered in Vietnam. See the Guidelines for the Scheduling of Specific Commitments under GATS, S/L/92 (28 March 2001)

[48] See Dự thảo Nghị định Quản lý, Cung cấp, Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet và Nội dung Thông tin Trên Mạng [Draft Decree on Management, Provision, [and] Use of Internet Services and Network Information Content], the third version, available at http://mic.gov.vn/layyknd/trang/dựthảonghịdinhInternet.aspx, (last visited April 20, 2014) (Viet.).

[49] See April Version, Art. 20.1.

[50] See April Version, Arts. 15 and 20.1.

iii. Censorship and International Trade Law Constraints

However, in the current context of Vietnam, there are international factors that may restrain the successful implementation of the above regulatory structure.

In particular, since 2000 Vietnam has entered into a number of international trade arrangements, in which the commitments by Vietnam constitute restraints or prohibitions against market access limitations of this type. Key international trade arrangements include the Bilateral Trade Agreement between Vietnam and the U.S. in 2000, Vietnam’s World Trade Organization membership beginning in 2007, and a number of regional trade agreements through the ASEAN.

As a part of these trade arrangements, Vietnam made market access commitments on specific service sectors, including telecommunications services, computer and related services, distribution services, and advertising services, among others.[51] Accordingly, Vietnam cannot impose any form of market access limitations[52] on the cross-border supply of a specific service included in its Service Schedule unless the limitation is explicitly mentioned in the Service Schedule or such restrictions justify the exemptions provided under the applicable trade agreement.[53] For example, where online services are included in Vietnam’s Service Schedule and no market access limitation was explicitly reserved therein, a prohibition against cross-border supply of these services might violate Vietnam’s obligations under the relevant international trade agreements.

The above context might explain why Decree No. 72 vaguely provides that foreign suppliers of “public information across the border, which are used in Vietnam or accessed from Vietnam, shall comply with Vietnam’s relevant laws.”[54] The Decree also deferred to the MIC for detailed provisions on the provision of public information across the border.[55] Similarly, the April 2012 version of the Draft Decree on IT Service removed the prohibition against the cross border supply of cloud computing services, database center services, and web search portal services. Rather, foreign suppliers are permitted to provide these services on a cross-border basis as long as that they do so through local branches or local intermediaries. Although the consistency of this revised provision with Vietnam’s international trade commitments is still questionable, if adopted as such, it will likely serve as one of the new mechanisms for the government to exercise their control over the content provided through cross-border online intermediaries’ services. In such cases, the local presences, local partners or agents of the foreign online intermediaries will have to comply with the authority’s requirement, and thus directly lend assistance to the authority in controlling Internet content.

In short, this section explains how ideology protection and content censorship needs shaped the regulation of online intermediaries in Vietnam. The vast increase in the volume of Internet users plus the popularity of online platforms, which are hosted both in Vietnam and overseas, have recently required the government to exercise their extensive control at the online intermediary level. A number of regulations have been put in place and some additional measures are being proposed to realize this objective. As such, online intermediaries are expected to comply with more and more local requirements, which hopefully will be within the scope of the international trade commitments of Vietnam.

[51] See for example, the World Trade Organization, Working Party on The Accession of Viet Nam, Schedule CLX – Vietnam, Part II – Schedule of Specific commitments in Services, WT/ACC/VNM/48/Add.2 (Oct. 27, 2006), available at http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/a1_vietnam_e.htm.

[52] There are six specific forms of market access limitation listed under the GATS Art. XVI.2.

[53] See GATS, Arts. XVI (providing the principle on market access) and Art. XIV (providing the general exceptions which allow WTO members to maintain or adopt measures that are inconsistent with GATS principles).

[54] Decree No. 72, Art. 22.1.

[55] Decree No. 72, Art. 22.2.

3. Traditional Fears

Like many other countries in the world, the Vietnamese government has concerns regarding the risks the Internet poses to national security, online transaction frauds, data privacy, and network security. These fears also contribute to more stringent regulations against online intermediaries.

i. National Security Risks

Since the 1990s, the government has set strict regulations on the use of the Internet by the Party, the government, public security, and national defense function agencies. Specifically, a private network must be established for Internet connection, the information flow on the network must be encrypted, and efficient technical measures must be applied to prevent data thief or unauthorized access that may cause harm to the system. Furthermore, the communications on the network must be controllable.[56] The recent revelation of NSA surveillance programs such as PRISM[57] and MUSCULAR[58] raised even more concerns regarding the exposure to national security risks through Internet use. The requirement of server localization imposed on certain forms of online intermediaries, among other things as discussed above, also serves as an effort to respond to this set of concerns.

[56] Decree No. 21, Art. 20.

[57] PRISM enables NSA to collect data from U.S. electronic communications service providers according to the procedures provided under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) (50 U.S.C. §1881a). See Director of National Intelligence, Facts on the Collection of Intelligence Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, available at http://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/press-releases/191-press-releases-2013/871-facts-on-the-collection-of-intelligence-pursuant-to-section-702-of-the-foreign-intelligence-surveillance-act, (last visited Jan. 22, 2014). Disclosed participants to this program include Microsoft, Google, Yahoo!, Facebook, PalTalk, YouTube, Skype, AOL, Apple. Data collected through PRISM include information content of all types, such as e-mails, videos, voices, photos, and online social networking details, etc. See The Washington Post, NSA Slides Explain the PRISM Data-Collection Program, published on June 6, 2013, updated on July 10, 2013, available at www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/politics/prism-collection-documents/, accessed on January 22, 2014.

[58] MUSCULAR program is a form of upstream data collection, which collects “communications on fiber cables and infrastructure as data flows past.” See Craig Timberg, The NSA Slide You Haven’t Seen, The Washington Post, July 10, 2013, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/the-nsa-slide-you-havent-seen/2013/07/10/32801426-e8e6-11e2-aa9f-c03a72e2d342_story.html?hpid=z1, accessed on 23 January 2014. MUSCULAR is located in the UK and jointly operated by UK intelligence agency (Government Communications Headquarters) and the NSA. MUSCULAR daily taps communications content and metadata when the data travel, without being encrypted, across the privately owned or leased fiber-optic cables that internally connect multiple datacenters of companies like Google and Yahoo!. MUSCULAR returns twice as much data as PRISM. See Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani, NSA Infiltrates Links to Yahoo, Google Data Centers Worldwide, Snowden Documents Say, The Washington Post, October 30, 2013, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-infiltrates-links-to-yahoo-google-data-centers-worldwide-snowden-documents-say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-4166-11e3-8b74-d89d714ca4dd_story.html, accessed on January 23, 2014; see also Brett Max Kaufman, A Guide to What We Now Know About the NSA's Dragnet Searches of Your Communications, American Civil Liberties Union, August 9, 2013, available at https://www.aclu.org/blog/national-security/guide-what-we-now-know-about-nsas-dragnet-searches-your-communications, accessed on January 22, 2014.

ii. Online Frauds

Together with the growth of e-commerce activities in Vietnam, alarming scams and frauds have also emerged that demand regulation. The Vietnamese market has grown to include various forms of online business, including online marketing and promotion, online sales, online auctioning, online payments, and online training, among others.[59] However, the issue of trust seems to drag down e-commerce development in the country. The concerns range from fraudulent online activities, deceptive advertisements, security for online payments, and e-signature and e-transaction validity.

For example, the Muaban24 case involves a group of website owners who claimed to organize a trading platform for e-commerce services. Participants to this platform must contribute an initial amount of cash to own a virtual store on the website. The owners of the virtual store, instead of conducting any actual online trading activities on the stores, enjoyed a share of the money taken from every additional participant that they recruited.[60] The website owners themselves made money by also received a share of these payments.[61] Outside the online world, a similar business model for the sale of goods, as opposed to services, would constitute an illegitimate multi level marketing activity, (similar to a “pyramid scheme” in other jurisdictions), which is prohibited under the Competition Law of Vietnam.[62] Meanwhile, the company masked itself as an e-commerce business even in the absence of appropriate licenses from the authorities.[63] By August 2012, Muaban24 had thousands of participants, sold 120,000 virtual stores, collected approximately USD30 million, and operated in 32 over 64 provinces in Vietnam.[64] The website owners were arrested and charged with “fraudulent appropriation of property” in numerous provinces.[65] This case has raised serious concerns regarding the effectiveness of State management as to online business activities, as well as trust issues surrounding e-commerce.[66]

In addition, there were reported cases where intermediaries for online promotion and online group deals failed to remit service payment to service providers.[67] Users also complained about the quality of the services, which either failed to meet what was advertised or was subject to discrimination by the service suppliers.[68] Furthermore, a survey conducted by PayPal in 2012 revealed that 43% of those surveyed refrain from purchasing online due to risk concerns.[69]

Key factors contributing to the above issues include the immaturity of e-commerce activities in Vietnam, users’ lack of awareness and experience, and ineffective enforcement of existing regulations. The government itself observed that many new forms of online business were “self-initiating” and blamed the above-mentioned situation to the “lack of strict surveillance by appropriate competent authorities.”[70] Thus, it called for new specific regulations, noting in particular the fundamentally different nature of e-commerce transactions, where, unlike in-person transactions, buyers and sellers do not directly interact.

Decree No. 52[71] on e-commerce was part of the governmental efforts to address the above concerns. It is unclear to which extent the specific measures under Decree No. 52 may help improve trust and thus boost e-commerce activities in Vietnam. However, it is certain that under Decree no. 52 online intermediaries are subject to more compliance requirements. Specifically, owners of e-commerce business websites[72] and e-commerce service websites[73] must respectively conduct notification[74] and registration[75] procedures with the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Notably, this requirement also applies for foreign owners of websites using .vn domain names.[76]

Decree No. 52 also emphasizes transparency in e-commerce by requiring the disclosure of certain information for specific types of websites. For example, e-commerce business websites must disclose website owners’ identity, information of the products and services on sale, payment and delivery methods, general terms of transaction, limitations on liability, dispute settlement mechanisms, and data security protection.[77] Furthermore, the Decree provides a broad range of prohibited acts,[78] which specifically address Muaban24 and group deal cases discussed above. Accordingly, despite the aforementioned loophole of the existing Competition Law, activities akin to illegitimate multi level marketing of services on e-commerce websites become illegal under Decree No. 52. Other steps to promote trust in e-commerce include recognizing the validity of electronic evidence,[79] clarifying the effectiveness of online contracts,[80] introducing mechanisms to rate websites’ creditability, data protection policies, and to authenticate electronic contracts, [81] and providing measures to secure online payments.[82]

[59] See Bộ Công Thương [Ministry of Industry and Trade], Báo cáo Thương mại Điện tử 2012 [2012 Report on E-Commerce] (December 2012), http://www.vecita.gov.vn/App_File/laws/3afc0508-107b-4ff4-9687-59b8a975cf79.PDF.

[60] See Vũ Văn Tiến - Hồng Kỹ, Vụ Muaban24: Cách thức Kinh doanh Đang Tạo Dư luận Tiêu cực [Muaban24 Case: A Business Model That Is Causing Negative Public Opinion], Dân Trí (July 28, 2012; 6:38), http://dantri.com.vn/ban-doc/vu-muaban24-cach-thuc-kinh-doanh-dang-tao-du-luan-tieu-cuc-623702.htm.

[61] See Vũ Văn Tiến - Hồng Kỹ, Các “Sếp Sòng” Muaban24 Kiếm Bao nhiêu Tiền? [How Much does Muaban24 “Chiefs” Have Earned?], Dân Trí (Aug. 4, 2012; 7:38), http://dantri.com.vn/kinh-doanh/cac-sep-song-muaban24-kiem-bao-nhieu-tien-626172.htm.

http://dantri.com.vn/event/muaban24-vu-an-rung-dong-2023.htm.

[62] See Luật Cạnh tranh [Competition Law] No. 27/2004/QH11, adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on Dec. 3, 2004, Art. 48. Illegitimate multilevel marketing activities under this Law cover the marketing of goods only, not services.

[63] See Vũ Văn Tiến - Hồng Kỹ, Vụ Muaban24: Cách thức Kinh doanh Đang Tạo Dư luận Tiêu cực [Muaban24 Case: A Business Model That Is Causing Negative Public Opinion], Dân Trí (July 28, 2012; 6:38), http://dantri.com.vn/ban-doc/vu-muaban24-cach-thuc-kinh-doanh-dang-tao-du-luan-tieu-cuc-623702.htm.

[64] See id.

[65] See Hồng Kỹ - Vũ Văn Tiến, Bắt Khẩn cấp 4 Nhân vật Chóp bu Đường dây Muaban24 [Urgently Arrest 4 Top Personnel of Muaban24 Chain] (Aug. 2, 2012), http://dantri.com.vn/xa-hoi/bat-khan-cap-4-nhan-vat-chop-bu-duong-day-muaban24-625684.htm (regarding the arrest in Hanoi). See also An ninh Thủ đô, Tiếp tục Bắt giữ Nhiều Lãnh đạo Chủ chốt Của Muaban24 [Continue to Arrest Multiple Key Personnels of Muaban24] (citing Dân Trí) (Aug. 18, 2012), http://www.anninhthudo.vn/Phap-luat/Tiep-tuc-bat-giu-nhieu-lanh-dao-chu-chot-cua-Muaban24/460112.antd.

[66] See Group of Reporters, Thương mại Điện tử bị... Vạ lây vì Muaban24 [E-Commerce’s Reputation Is …. Incidentally Hurt by Muaban24] (Aug. 5, 2012; 9:00), ICTNews, http://ictnews.vn/kinh-doanh/thuong-mai-dien-tu-bi-va-lay-vi-muaban24-104086.ict.

[67] See Anh Quân, Mua Theo Nhóm – Được Ít Mất Nhiều [Group Deals – Gain Little Lose A Lot], VN Express (Nov. 22, 2012; 12:12), http://kinhdoanh.vnexpress.net/tin-tuc/vi-mo/mua-theo-nhom-duoc-it-mat-nhieu-2724174.html.

[68] See id.

[69] See The Box, Thanh toán Trực tuyến tại Việt Nam: Chưa đủ An toàn? [Online Payments in Vietnam: Not Safe Enough?], Lao Động (Oct. 19, 2012; 4:20 PM.), http://laodong.com.vn/sci-tech/thanh-toan-truc-tuyen-tai-viet-nam-chua-du-an-toan-88306.bld.

[70] See Tờ trình Chính phủ Dự thảo Nghị định về Thương mại Điện tử [Proposal to the Government regarding the Draft Decree on Electronic Commerce], Part I, available at http://www.vibonline.com.vn/Files/Download.aspx?id=2449 (last visited Apr. 20, 2014).*

[71] Nghị định về Thương mại Điện tử [Decree on E-commerce] No. 52/2013/ND-CP, issued by the Government of Vietnam on May 16, 2013 (hereinafter “Decree No. 52”) (Viet.).

[72] Websites established to promote and/or sell the goods and/or services of the website owners. See Decree No. 52, Arts. 24.1 and 25.1.

[73] Websites that provide a platform for third parties to conduct e-commerce trading activities, including e-commerce platform websites, online auction websites and online promotion websites and other websites to be added by the authorities in the future. See Decree No. 52, Arts. 24.2 and 25.2.

[74] See Decree No. 52, Art. 27.1.

[75] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 36.1, 41.1, 46.1, and 55.1.

[76] See Decree No. 52, Art. 2.1(c).

[77] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 28-34.

[78] See Decree No. 52, Art 4 (including the following acts: organizing a marketing or trading network for e-commerce services, to which participants must contribute an initial amount to buy the service, and are rewarded for recruiting new participants; taking advancate of the name of e-commerce operation to illegally mobilize capital from other traders, organizations, or individuals; committing fraud to consumers on e-commerce activities, among others.

[79] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 9-14.

[80] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 15-23 (Decree No. 52 sets out clearer conditions for establishing the legal validity of e-commerce contracts. Accordingly, informational integrity of a document is established when parties agree to use certain measures such as using e-signatures certified by lawful certification organizations, or storing documents on the systems of licensed e-contract authentication organizations.)

[81] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 60-63 (a license from the MOIT is required in order to provide the following services: Rating the creditability of e-commerce websites; rating and certifying the policy (of a website owner) regarding the protection of personal information in e-commerce; and electronic contract authentication.)

[82] See Decree No. 52, Arts. 74 and 75 (owners of websites with online payment functions and suppliers of online payment services are subject to specific obligations under Decree No. 52 regarding the safety and confidentiality of online payment transactions. They may be held jointly liable for any damage caused by the illegal disclosure, amendment, reproduction, cancellation, deletion, or transfer of online payment information via the website. In addition, website owners who develop their own online payment solutions to support the online sale of their goods must apply specific measures to ensure safety and confidentiality of customer data.)*

iii. Data Privacy Protection Concerns

The Civil Code of Vietnam addressed privacy protection issues even before the Internet was introduced in Vietnam.[83] When the government first introduced the Internet in Vietnam in 1990s, it also emphasized the need to protect personal privacy.[84] “Personal information,” though defined differently in different contexts, is protected under the IT Law,[85] the Law on Electronic Transactions,[86] the Law on Consumer Protection,[87] and their implementing regulations. The collection, use, processing, transfer, and storage of personal information is subject to specific restrictions, including, inter alia, adequate disclosures, required security measures, and required consent of the data subject.

In particular, the data protection responsibilities rest on the entity that collects, processes, uses,[88] and stores[89] the data, regardless of where the data is stored. As such, the failure to obtain consent and to secure the data at any of these steps will result in liabilities for online intermediaries, including offshore service suppliers who process and host the relevant data outside Vietnam.

[83] Civil Code 1995 (Article 34 recognizes the right of individuals to have their privacy respected and protected by law; the collection and publication of individual privacy’s information require consent). A similar principle was included in the current Civil Code No. 33/2005/QH12, adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on Jun. 14, 2005 (Viet.), Arts. 31 and 38.

[84] Decree No. 21, Art. 3.3.

[85] See Luật về Công nghệ thông tin [Law on Information Technology, No. 67/2006/QH11 adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on Jun. 29, 2006 (“IT Law”), Arts. 21 and 22 (Viet.).

[86] See Luật Giao dịch Điện tử [Law on E-Transactions], No. 51/2005/QH11 adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on Nov. 29, 2005, Art. 46 (Viet.).

[87] See Luật Bảo vệ Quyền lợi Người Tiêu dùng [Law on Protection of Consumers’ Rights] No. 59/2010/QH12, adopted by the National Assembly of Vietnam on Nov. 17, 2010, Art. 6 (Viet.).

[88] Art. 21, IT Law (Viet.).

[89] Art. 22, IT Law (Viet.).

iv. Network Safety – Malwares & virus

Vietnam also shares the common fear of malware and virus attacks. In order to address this fear, the government has designed regulations to control not only individual hackers’ behaviors, but also those of online intermediaries.

Although spreading spam and malware is subject to criminal liability under Vietnamese law,[90] individual hackers are not easily identifiable ex-ante and the liabilities are imposed on them only when the infringements have occurred. Therefore, the government also requires online intermediaries – the limited number of government-licensed entities/the chokepoints – to apply measures to prevent the risk.[91]

For example, in order to obtain a license to provide online social networking services, suppliers must have measures to ensure information safety and security.[92] Owners of websites that have online payment functions must conduct specific practices to ensure security and confidentiality of customers’ payment transactions.[93] Furthermore, in case of “serious Internet incidents,”[94] the party facing the incident must report to appropriate members of the incident response network, including the relevant ISPs and the Vietnam Computer Emergency Response Team (VNCERT), for a coordinative solution.[95] The failure to comply with statutory information security requirements may result in administrative fines, penalties, sanctions, or civil actions.[96]

Despite all of these efforts, in May 2014 the Microsoft Security Intelligence Report announced that Vietnam was one of the top five countries with the highest rates of malware incidence.[97] Stricter liabilities against online intermediaries may thus be imposed in the near future to address this issue. In fact, the government is now introducing a draft law on information security. The proposed bill addresses information safety issues from multiple perspectives, including, inter alia, liabilities of online intermediaries in detecting, preventing and handling malwares, required information security breach responses, encryption technology control, information technology import control, and licensing requirements for security certification services.[98]

In short, this section assesses the liability of online intermediaries from the perspective of the concerns that Vietnam commonly shares with other jurisdictions. The current regulatory framework is designed to include online intermediaries’ responsibilities to protect national security, prevent online frauds, protect data and privacy of users, and secure the safety of the entire network. Failure to comply with such requirements will result in liability designated by law. Since these concerns remain ineffectively addressed, more stringent regulations might soon be added.

[90] See Luật Hình sự [Penal Code] No.15/1999/QH10 dated December 21, 1999, as amended under Luật Sửa đổi, Bổ sung Một số Điều của Bộ Luật Hình sự [Law Amending and Supplementing Certain Provisions of the Penal Code] No. 37/2009/QH12, Arts. 224, 225, 226a, and 226b.

[91] See Decree No. 55, Art. 18.3.

[92] Decree No. 72, Art. 23.5(dd).

[93] Decree No. 52/2013/ND-CP, Art. 74.2 (required measures include, among other things, encryption of information, access control, early detection, warning, and prevention of illegal access, and data retention and data retrieval function).

[94] Thông tư Quy định về Điều phối Các Hoạt động ứng cứu sự cố mạng Internet Việt Nam [Circular Regulating the Coordination of Responses to Internet Incidents in Vietnam] No. 27/2011/TT-BTTTT (hereinafter Circular No. 27), Art. 2 (defining “serious Internet incidents” as incidents that caused, has caused, or will potentially cause information security failures on the Internet that occur on a large scale, spread quickly, threaten serious harm to computer and Internet network systems, cause serious loss of information or which require substantial national or international resources to resolve.)

[95] See Circular No. 27, Art. 7.

[96] See IT Law, Art. 22; Civil Code, Art. 25.

[97] See Đỗ Nguyễn, Việt Nam thuộc 5 Quốc gia có Tỉ lệ Nhiễm mã độc cao nhất Thế giớI [Vietnam within top 5 Countries with the Highest Rate of Malware Affection], PC World VN (May 17, 2014: 18:51), http://www.pcworld.com.vn/articles/kinh-doanh/an-toan-thong-tin/201...viet-nam-thuoc-5-quoc-gia-co-ti-le-nhiem-ma-doc-cao-nhat-the-gioi/.

[98] See Dự thảo Luật An toàn Thông tin [Draft Law on Information Security], available at http://mic.gov.vn/layyknd/Trang/LUẬTANTOÀNTHÔNGTINSỐ.aspx, (last visited May 10, 2014).

4. The Fear of the Failure to Localize the Benefit of Online Services – Domestic Call

Many countries, including Vietnam, are concerned about the fact that cross-border online businesses incurred profit locally, while leaving a small portion or no portion of such income behind domestically. So the question is how to localize the benefits of cross-border online services.

Potential answers include: Support domestic service suppliers to compete against foreign suppliers; mandate or encourage a profit sharing arrangement with local entities; and subject foreign service suppliers to greater regulatory burdens, such as imposing licensing requirements, requiring localization of infrastructure, or requiring the establishment of local entities. It appears that the Vietnamese government has tried all of these, which have had a substantial effect in shaping the business environment for online intermediaries, particularly for foreign online intermediaries.

Overall, the policy has been to promote and facilitate homegrown businesses, including local online intermediaries’ businesses and the business activities by foreign intermediaries that also benefit local businesses. In 2009, the Politburo of the Communist Party of Vietnam announced a campaign titled, “Vietnamese people prefer Vietnamese products.”[99] In line with this campaign, the Prime Minister of Vietnam approved the National Strategy on “Transforming Vietnam into an Advanced ICT Country” in 2010.[100] “Improve the capacity and competitiveness of Vietnamese enterprises” and “develop Vietnam’s ICT brand-name products and services” are two key missions of this Strategy.[101] When Mr. Nguyen Bac Son became MIC Minister in 2011, the MIC implemented these missions by initiating the “Program on Promoting the development of Vietnam ICT brand-name products and services (VIBrand).”[102]

One of the first moves - allegedly driven by the Vietnamese government – that affected a foreign online intermediary was the 2009 Facebook blocking.[103] In 2010, soon after the blocking was reported, go.vn, a homegrown online social networking service (run by VTC Intercom, a State owned company)[104] was introduced to users. The site had the stated goal to “knock out Facebook.”[105] Though go.vn was reported to be State sponsored, the government has since denied its involvement in the Facebook blocking.

Notably, unlike the blocking in China, which is conducted at the Internet protocol level,[106] Facebook access from Vietnam is blocked at the domain name system (DNS) level. Users can easily circumvent the blocking by using a proxy server or a virtual private network, or by changing their DNS.[107] Thus, an alternative explanation by some local experts was that the blocking might not be to afford domestic protection.[108] Rather, the main purpose was likely to draw foreign service suppliers’ attention to the fact that the local authority is looking for their cooperation[109] in achieving governmental interests, including, for example, localizing certain portions of the locally generated income and obtaining convenient access to control online content accessible to local users.

In fact, despite the alleged blocking, Facebook services in Vietnam are still growing significantly.[110] Interestingly, this growth is happening in conjunction with certain local arrangements by Facebook. In January 2011, Facebook hired a Policy and Growth Manager for Vietnam.[111] In March 2011, Facebook signed the Memorandum of Understanding with a local partner, FPT Group, regarding FPT’s membership to Facebook’s Preferred Developer Consultant. Accordingly, the local partner will “develop specific mobile-based applications and provide advertising services for Facebook in Vietnam.”[112] Most recently, Facebook appointed T&A Ogilvy, a local partner, as its media representative in Vietnam beginning in January 2014.[113] This way of doing business by foreign service suppliers is welcomed by the government for a number of reasons. First, a part of the income incurred locally will be shared with the local partner, and thus captured domestically. Second, this local entity serves as the local contact point, bridging the foreign supplier and the local authority for liaison functions when necessary. Third, the local partner may also serve as the point of control in terms of online content management and compliance with relevant local tax obligations.

Furthermore, the Government attempted to localize the benefits earned by foreign online businesses by proposing regulations that force cross border service suppliers to enter into commercial arrangements with local partners, do business through local intermediaries,[114] establish local entities, or locate infrastructures in Vietnam.[115] As an additional effort, in April 2012, the Ministry of Finance of Vietnam officially subjected foreign suppliers generating income from online advertising and marketing to tax obligations in Vietnam.[116] With these requirements, certain parts of the income earned from the domestic market may remain within Vietnam. In addition, foreign service suppliers will be subject to the relatively equal footing with domestic suppliers in terms of establishing local infrastructure, obtaining required local licenses, and complying with other local requirements.

As such, it is not a surprise that major foreign online intermediaries such as Google and Facebook will soon be subject to more and more scrutiny from the local government. The criteria used by the local government as the basis to exercise its authority are broadly whether the relevant sites are used in Vietnam or accessed from Vietnam, as mentioned by Decree No. 72.[117] The number of Vietnamese users reaching/accessing/using the foreign site might also be a relevant criteria depending on how the regulations implementing Decree No. 72 will be crafted.[118]

All in all, Vietnamese online intermediaries will likely enjoy a facilitating environment, while foreign online intermediaries will be subject to more stringent local disciplines when generating income from Vietnam. Most of the constraints on the latter will likely be aimed at capturing a certain portion of the locally generating income inside Vietnam and facilitating censorship by the local authority.

[99] TTXVN, Bộ Chính trị Vận động Người Việt Dùng Hàng Việt [The Politburo Campaigns for Vietnamese People to Use Vietnamese Products] (Aug. 7, 2009, 11:09), available at http://dantri.com.vn/su-kien/may-bay-malaysia-mat-tich-mot-hanh-khach-dung-ho-chieu-an-cap-342309.htm (Viet.).

[100] NSCICT and MIC, White Book 2012: Information and Data on Information and communication Technology: Vietnam 2012, Information and Communications Publishing House, 15 (2011).

[101] Id.

[102] Id.

[103] OpenNet Initiative, Vietnam, Aug. 7, 2012, 387-388, available at http://access.opennet.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/accesscontested-vietnam.pdf.

[104] See Intercom VTC, http://intecom.vtc.vn/vn/about-us (last visited May 10, 2014).

[105] Anh Trọng, Go.vn Sẽ Đánh bại Facebook [Go.vn will Knock out Facebook], Thegioididong (May 26, 2010), http://www.thegioididong.com/tin-tuc/govn-se-danh-bai-facebook-12450. See also James Hookway, In Vietnam, State ‘Friends’ You, Wall Street Journal (updated Oct. 4, 2010 12:01 a.m. ET), http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703305004575503561540612900?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB10001424052748703305004575503561540612900.html; Luke Allnutt, Fearing Facebook Vietnam Launches Its Own Social Networking Site, Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty (Oct. 5, 2010), http://www.rferl.org/content/Fearing_Facebook_Vietnam_Launches_Its_Own_SocialNetworking_Site_/2177003.html.

[106] See H.C., Banned, Maybe. For Some., The Economist (Nov. 10th, 2010, 22:40), http://www.economist.com/blogs/babbage/2010/11/facebook_vietnam.

[107] See id. See also OpenNet Initiative, Vietnam, Aug. 7, 2012, 387-388, available at http://access.opennet.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/accesscontested-vietnam.pdf.

[108] See Goutama Bachtiar, Nguyen Ngoc Hieu on the State of Social Networks in Vietnam, E27 (Nov. 30, 2011), http://e27.co/nguyen-ngoc-hieu-on-the-state-of-social-networks-in-vietnam/.

[109] See id.

[110] See Tuoitrenews, Facebook Users in Vietnam Grow 200% in One Year, Tuoitrenews (updated Oct. 19, 2012; 16:37), http://tuoitrenews.vn/features-news/2967/facebook-users-in-vietnam-grow-200-in-one-year. See also Anh-Minh Do, Vietnam’s Facebook Penetration Hits Over 70%, Adding 14 Million Users in One Year, Techinasia (Sept. 25, 2013, 2:30 PM), http://www.techinasia.com/facebook-12-million-users-vietnam/.

[111] See the Manager’s LinkedIn profile at https://www.linkedin.com/pub/tuoc-huynh/2/624/435.

[112] FPT, Facebook and PPT Announces Cooperation in Vietnam (April 4, 2011; 00:00), http://www.fpt.com.vn/en/newsroom/press_releases/2011/04/04/24492/.

[113] SGT, Facebook Officially Enters Vietnam, Vietnamnet, (Jan. 27, 2014, 13:15), http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/science-it/94575/facebook-officially-enters-vietnam.html.

[114] See Dự thảo Nghị định về Dịch vụ Công nghệ Thông tin [Draft Decree on Information Technology Services], Version 3.8, Art. 19.3, available at http://www.vibonline.com.vn/Duthao/1250/Nghi-dinh-ve-dich-vu-cong-nghe-thong-tin.aspx, (last visited Jan. 1, 2014) (Viet.).

[115] See Dự thảo Nghị định về Dịch vụ Công nghệ Thông tin [Draft Decree on Information Technology Services], qtcs.com, Apr. 2012, Art. 20.1, available at http://qtsc.com.vn/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=63cd7c9e-065c-4f06-a6a0-93ab819b7ce2&groupId=18, (last visited Jan. 1, 2014) (Viet.).

[116] Thông tư Hướng dẫn Thực hiện Nghĩa vụ Thuế Áp dụng Đối với Tổ chức, Cá nhân Nước ngoài Kinh doanh Tại Việt Nam hoặc có Thu nhập tại Việt Nam [Circular Guiding the Implementation of Tax Obligation Applicable to Foreign Organizations [and] Individuals Doing Businesses in Vietnam or Incurring Income from Vietnam] No. 60/2012/TT-BTC issued by the Ministry of Finance on Apr. 12, 2012, Art. 4.4 (Viet.).

[117] Decree No. 72, Art. 22.1.

[118] This is hinted from the provisions on cross borders supply of public information to large users in Vietnam under the draft version of the then adopted Decree No. 72.

III. Regulations Reflecting Hopes

The above risks and concerns, though prevalent, are only a one-sided reflection of online activities in Vietnam. Various regulations and policies adopted by the Government through different periods of time also reflect a strong hope for growth opportunities brought by the Internet. According to these policies and regulations, online intermediaries’ roles are recognized in a number of fields.

1. Embracing New Opportunities for Economic Growth

As a result of the command-and-control approach in the 1990s period, Internet developments in Vietnam were constricted by the capabilities of the Vietnamese regulator. The Communist Party of Vietnam itself perceived the development of Vietnamese technology information industry in 2000 as “outdated”, “low,” and “far lagging behind” the level of development of other countries.[119] These disappointing outcomes and the desire to incorporate Internet growth into the wider development agenda of the country demanded that Vietnam amend its strategy. The country embraced this hope by making a leap in its economic growth through unleashing and promoting the potentials brought by the information technology (“IT”) industry.[120]

The Party leaders adopted specific plans to promote IT application and development in order to serve the modernization and industrialization processes in Vietnam. The plans included measures to encourage the large scale application of IT, train human resources for the IT industry, create a supportive environment for investments in the IT sector, accelerate the construction of Internet and telecommunications infrastructure, and renovate state administration in the field.[121] This top-down instruction was implemented in three key regulations that substantially determined the roles and liabilities of online intermediaries: Decree No. 55 and its subsequent replacements,[122] the Law on Information Technology,[123] and Joint Circular No. 07. [124]

[119] Chỉ thị số 58/CT-TW về Đẩy mạnh Ứng dụng và Phát triển Công nghệ Thông tin Phục vụ Sự nghiệp Công nghiệp hoá, Hiện đại hoá [Directive No. 58/TW on Promoting the Application and Development of Information Technology in Support of the Modernization and Industrialization Process], approved by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam on Oct. 17, 2000, Part I (Viet.) (hereinafter “Directive No. 58”).

[120] See id.

[121] See id. Part II.

[122] Nghị định 55/2001/NĐ-CP ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2001 về Quản lý, Cung cấp và Sử dụng Dịch vụ Internet [Decree No. 55/2001/ND-CP dated August 23, 2001 regarding the Management, Provision and Use of Internet Services] (Viet.).

[123] Luật Công nghệ Thông tin của Quốc hội nước Cộng hoà Xã hội Chủ nghĩa Việt Nam số 67/2006/QH 11 ngày 29 tháng 6 năm 2006 [Law on Information Technology No. 67/2006/QH 11, adopted by the National Assembly of the Socialist Republic ò Vietnam on 29 June 2006] (Viet.) (hereinafter “IT Law”).

[124] Thông tư Liên tịch Quy định Trách nhiệm Của Doanh nghiệp Cung cấp Dịch vụ Trung gian Trong việc Bảo hộ Quyền Tác giả và Quyền Liên quan trên Môi trường Mạng Internet và Mạng Viễn thông [Joint Circular on the Liabilities of Intermediary Service Suppliers in Protection of Copyrights and Related Rights on the Internet and Telecommunications Network Environment] No. 07/2012/TTLT-BTTTT-BVHTTDL, jointly issued by the Ministry of Information and Communications and the Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism on Jun. 19, 2012 (hereinafter “Joint Circular No. 07”) (Viet.).

i. Decree No. 55 and Its Subsequent Replacements - Doors Opened for Online Intermediaries

Adopted in 2001, Decree No. 55 explicitly set forth the principle that “regulatory capability must keep up with developments’ demand.”[125] According to this principle, instead of constricting Internet developments to the authority’s regulatory capability (as adopted during the 1991-2000 period), Internet developments are the goals that regulatory measures serve to achieve.

The Decree also outlined the goal of “developing diversified Internet services at high quality and reasonable price in order to serve the nation’s industrialization and modernization progress.”[126] In particular, the Decree explicitly acknowledged the roles of Internet services in popularizing government policies to the public and facilitating the advertisements of private goods and services on the Internet.[127]