Turkey (eBay Case)

This paper provides an analysis and evaluation of the situation for online intermediaries in Turkey, with a focus on the problems faced by eBay after it acquired www.gittigidiyor.com, which was operating with a similar business model in Turkey.

Turkey (eBay Case)

Authors: Nilay Erdem and Yasin Beceni

BTS & Partners

Abstract: This case study provides an analysis and evaluation of the situation for online intermediaries in Turkey, with a focus on the problems faced by eBay after it acquired www.gittigidiyor.com, which was operating with a similar business model in Turkey. Within the scope of this case study, the online intermediary ecosystem and legislative environment in Turkey are first examined and then the above-mentioned eBay Case is analyzed in detail. The study concludes that basic problems for online intermediaries in Turkey are a result of the lack of proper legislation, and the government’s attempts to suppress and control the Internet and online intermediaries in Turkey. Furthermore, Turkish courts’ lack of understanding of online intermediaries’ business models may cause those courts to render faulty decisions. However, despite these negative aspects, Internet usage and activities of online intermediaries in Turkey continue to grow.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. General Overview of the Online Intermediaries Ecosystem in Turkey

A. Internet Usage

B. Ecosystem of Online Intermediaries

C. National Intermediaries

III. Governance and Responsibility Mechanisms

A. Overview of Internet Governance in Turkey

B. Regulations Effecting E-Commerce Ecosystem

1. Regulations Directly Applicable to the Internet Intermediaries

2. General Rules and Regulations Applied to Internet Intermediaries in Certain Events

C. Main Governance Mechanisms

IV. Liability

A. Liability Framework

1. Defamation

2. Personal Right Violations

3. Crimes Against Ataturk

4. Copyright Protection

5. Additional Regulations

B. Safe Harbors

C. Enforcement

D. Significant Cases

V. eBay Case Study

A. Information About eBay and Gitti Gidiyor (eBay’s Local Subsidiary in Turkey)

B. Challenges for eBay as an Intermediary Operating in Turkey

1. Challenges Related to Customs Issues

2. Challenges Related to V.A.T. Liabilities

3. Challenges Related to Sales of Products

C. Impact Assessment of the Challenges

D. Recommendations/Solutions in Light of the Specific eBay Case

VI. Conclusion

I. Introduction

This case study examines the challenges of e-commerce platforms in Turkey with a focus on problems faced by eBay after its acquisition of the company that owns www.gittigidiyor.com (“Gitti Gidiyor”), which operates according to an identical business model in Turkey. Before the discussion of Gitti Gidiyor, this study will first explain the online intermediary ecosystem in Turkey, mapping the general intermediary landscape and its legislative environment. After that, the study will review the eBay case in detail.

In 2011, eBay acquired Turkey’s leading third party e-commerce platform, Gitti Gidiyor. EBay operates in Turkey under Gitti Gidiyor and no separate eBay entity exists in the market. Therefore eBay does not directly face problems in Turkey, but experiences difficulties through Gitti Gidiyor.

II. General Overview of the Online Intermediaries Ecosystem in Turkey

A. Internet Usage

Internet use in Turkey is increasing day by day. With its dynamic and young population of more than 76 million, and improved Internet infrastructure and mobile penetration, Turkey has one of the highest Internet usage rates in the world. According to the official statistics agency of Turkey (Turkish Statistical Institute),[1] the 2013 Internet access rate for businesses was 90.8%, while the same rate in households was 49.1%. According to the data published by the World Bank[2] in 2013, 46.3% of the Turkish population has access to the Internet and Turkey is ranked 93rd in Internet access rates in the world.

[1] TurkStat, Use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Enterprises, Use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Households and Individuals (16-74 age group).

[2] The World Bank, based on the data gathered from the International Telecommunication Union, World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and database, and World Bank estimates.

B. Ecosystem of Online Intermediaries

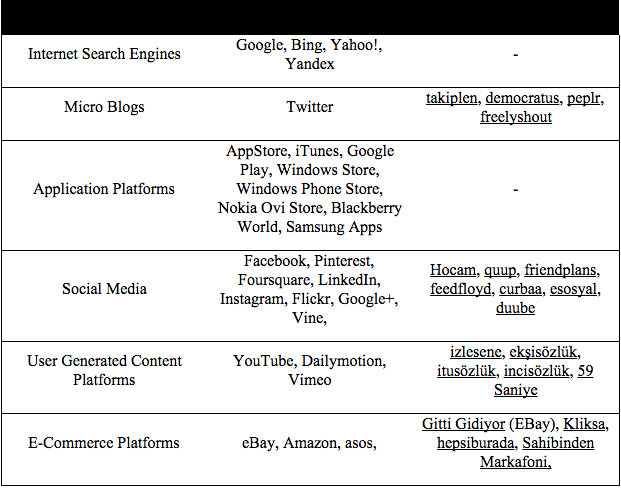

When we look at the ecosystem of online intermediaries, the main actors seem to be social media platforms and e-commerce websites. The table below shows the main providers by intermediary type:

Figure 1. Main intermediaries in Turkey

International and national intermediaries currently dominate the Turkish market, and national intermediaries are generally imitations of international entities and are often not as popular as their international counterparts.

Currently, Turkey is witnessing an explosion in its citizens’ use of online social media networks. It ranks 7th globally in the usage of Facebook and 10th for Twitter.[3] 93% of Turkish Internet users have Facebook accounts. Twitter follows Facebook with a usage rate of 72%, Google+ with a rate of 70%, LinkedIn with a rate of 33%, and Instagram with a rate of 26%. Currently, there are approximately 32,500,000 Facebook users in Turkey, approximately 41.59% of the population.[4] These rankings have made social media a powerful rival to the country’s mainstream media. “Facebook is the most popular social network in Turkey”, according to Social Bakers, “but recently Twitter and personal blogs have gained in popularity. Turkey’s mobile penetration is larger than Internet penetration, which means that people increasingly access their social networks from mobile phones.”[5] Furthermore, social media is heavily used for advertising purposes both by companies and politicians, as well as in social responsibility projects.

Within the context of e-commerce, Turkey’s e-commerce sector generated approximately 7 billion USD per year as of 2012 and it is expected to grow 15.8% every year until 2017.[6] Online shopping is very popular among Turkish people and it is expected to gain more popularity over time. Women and young people buy items online much more than other segments of society. Although Turkey’s e-commerce market is not as developed as the United States or the European Union, it has great potential to grow.

Turkish society uses the Internet intensely; however, all services that are available in the US and the EU are not available in Turkey. For example, Turkish citizens cannot currently obtain e-books from Google Play Store or the Apple App Store. The same situation exists for Google’s music and film services, as well as some of Google Maps’ features.

Generally speaking, Turkish usage tendencies of social media are similar to the rest of the world considering that most Turkish users use social media to stay connected with friends, share comments and photos, and keep up with the news and current events. Furthermore, social media websites such as blogs, Facebook, and Instagram are also used for the sale of second hand things. However, there is a cultural difference when it comes to matchmaking websites. Many people who use dating websites are searching for “serious relationships” or “marriage,” rather than a causal relationship. However, similar to the US, Turkish matchmaking websites target different demographics, with some tailored for religious people, lawyers, doctors, etc.

Twitter is a controversial but extremely popular social network in Turkey; in recent years, it has been one of the most-used tools for political and social expression. For instance, the Gezi Park protests of May and June 2013 showed an unexpected and extraordinary face of Turkish youth, a generation largely raised during a period devoid of widespread protests. This protest was largely motivated by the distribution of photos on social media that demonstrated a disproportionate use of force by police. Photos of their peers resisting water cannons and tear gas further inspired young people to join the protest. A micro blogging web site (delilimvar.tumblr.com) specifically aimed at protesters enabled them to report any excessive use of force by police. While most individuals who joined the demonstrations were not members of any political or social organization, social media allowed these previously non-activist youth to connect with each other. Additionally, protestors used social media to access information about the current situation in specific areas of the city where protests were planned. Likewise, individuals spread the contact information of lawyers and doctors available for aid over Facebook and Twitter.

The public reaction before the local election on March 30, 2014 is also illustrative of the use of Twitter for political and social expression. Before the election, an investigation into big corruption broke out in response to videos circulated on YouTube. The government immediately banned many YouTube links, but they couldn’t block the spreading of Twitter links, which provided a new way to reach the public. In particular, citizens have found Twitter’s “retweet” function to be especially useful to create public awareness during elections. After such developments, the ability of social media to allow people to express their opinion and organize for street protests was widely recognized by the government, academia, NGOs, and society itself.[7]

Turkish people often also use social network intermediaries like Facebook and Twitter to find blood and marrow for people who need them.[8] Many Internet celebrities will retweet or share requests for blood or marrow donation to spread them. The use of social media in such a way both creates public awareness for people in need, and generally increases blood and marrow donation rates.

LinkedIn, another international intermediary, has been popular in Turkish business life. Lots of people use LinkedIn to connect with business contacts and advance their career, find new job opportunities, as well as monitor friends and competitors.

YouTube and video websites are popularly used for watching old episodes of TV series, among other uses. Additionally, some professionals organize live business meetings on YouTube using the live stream feature.

As noted, some national intermediaries – imitations of international intermediaries such as Facebook and Twitter – are unsuccessful in Turkey. On the other hand, there are a couple of successful national intermediaries that have either copied an international concept by combining this concept with local cultural elements (such as underlying the privacy aspects of the site, providing additional payment options such as payment at the delivery, etc.); or have developed a fully national concept. In the field of e-commerce intermediaries, national intermediaries are more successful because of the trust relationship between website and user. The following paragraphs provide a couple of examples of successful national intermediaries in Turkey.

[3] Common Ground of Digital Markets E-Commerce: Place of Turkey in the World, Current Situation and Steps for the Future, Turkish Industry and Business Association, July 2014, Accessible via: http://www.tusiad.org/_ _rsc/shared/file/eTicaretRaporu-062014.pdf.

[4] Global Web Index Wave 11.

[5] http://businessculture.org/southern-europe/business-culture-in-turkey/social-media-guide-for-turkey/ 03.12.2014.

[6] Common Ground of Digital Markets E-Commerce: Place of Turkey in the World, Current Situation and Steps for the Future, Turkish Industry and Business Association, July 2014, page 35, Accessible via: http://www.tusiad.org/__rsc/shared/file/eTicaretRaporu-062014.pdf.

[7] Prof. Dr. B. Bahadır Erdem, Turkish Citizenship Law, 3rd Edition, Beta Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 2013, p. 76; An Examination of Gezi Park by Alternative Informatics Association, https://www.alternatifbilisim.org/wiki/Gezi_Park%C4%B1_De%C4%9Ferlendirmesi 26.09.2014.

[8] Although most of announcements are made individually, some of the Facebook groups are as follows (announcements repeatedly takes place on trend topic list of Twitter also): https://www.facebook.com/kanhayattir?fref=nf https://www.facebook.com/groups/kanaraniyor/?ref=ts&fref=ts https://www.facebook.com/iliknakli?ref=ts&fref=ts 03.12.2014.

C. National Intermediaries

The most important of the successful Turkish intermediaries is “ekşisözlük”. The name means “sour dictionary,” but it is not a dictionary in the strict sense because, though the site defines words and/or terms, users are not required to write correct definitions. Ekşisözlük is not only utilized by thousands for information-sharing on various topics ranging from scientific subjects to lifestyle issues, but is also used as a virtual socio-political community to communicate disputed political content and to share personal views.

Ekşisözlük is an open area to express opinions, but also it has strict rules for entries and selecting writers. Writers are selected based on their draft entries, so the site aims to achieve a high intellectual level. Despite this aim, ekşisözlük has been losing its intellectual capacity, and is becoming a more and more politicized platform. Most of the users are in the opposition against the government but there are also a high number of users that are pro-government. It is currently one of the biggest online communities in Turkey with over 400,000 registered users and about 54,000 writers. However, the platform had only approximately 10,000 writers a couple of years ago, and therefore it was a much more of a boutique platform at that time, as it could be considered a more closed community because of stricter membership rules and content management.

The founders of ekşisözlük do not allow “troll” users, banning fake users or users who do not follow the rules of platform. Because of this kind of “high intellectual level” perspective, some people found this platform pretentious, establishing another platform – “incisözlük” – as a reaction. After the popularity of ekşisözlük, many similar social media platforms popped up but have not became as popular as ekşisözlük or incisözlük. incisözlük is popular for its anarchic attitude and having no active administration to select and screen writers. However, while it still has a moderation system – like ekşisözlük – for the content, incisözlük allows the users to write about almost any type of content (e.g. pornographic, daily life, etc…), without any limitation or format restrictions. The website represents different sub-cultures that have grown in Turkey since the 2000s. Sarcasm, parodies of clichés, and hatred of intellectualism on ekşisözlük have made incisözlük nearly as popular as ekşisözlük.

Turkish intermediaries such as ekşisözlük and incisözlük are similar with Wikipedia in the way that they are sources of information. However, while Wikipedia is much more like an encyclopedia and aims to provide objective information on historic or scientific facts, ekşisözlük and incisözlük are much more focused on daily events such as political issues, football games, or other such developments. In addition to those current events, ekşisözlük and incisözlük also contain information on historic and scientific facts, like Wikipedia. However, ekşisözlük and incisözlük are much more dynamic (new entries are provided by users nearly every minute of the day) than Wikipedia.

Another successful national intermediary is Hocam, a social media platform like Facebook intended only for college students who live in Turkey. Students can share their videos or photos, as well as create social groups or events. Just as Facebook was structured at the beginning, Hocam users can only sign up if they are university students. Both Hocam and another Turkish social media platform, quup, are very similar to Facebook. However, while Hocam has achieved significant popularity, quup is not popular. Quup’s failure can be explained by its content management strategy. Quup is a social media platform, but it does not host content created by the users. Rather, it only hosts content created by the editors, fetched from newspapers, magazines, etc. Hocam’s success can be attributed to its unique theme and restricted member acceptance policies, explained above.

59saniye is a user generated content platform on which users can share or broadcast every kind of video as long as it is less than 59 seconds. Such a duration cap makes the site attractive for people who do not have lots of time to watch long videos or who do not like long videos. The motto of the website is “’cause 1 minute is too much time”, further demonstrating this intermediary’s concept. Another rising trend that allows new national intermediaries to flourish is e-commerce. For Turkish citizens, trust in e-commerce platforms is rising constantly, thereby increasing the opportunity for online shopping. Many e-commerce websites popped up after reinforcing their security measures and the numbers of online shoppers are increasing constantly as a consequence. The most popular national intermediaries that host e-commerce platforms are Markafoni, Trendyol, hepsiburada, sahibinden, kliksa, and n11.

III. Governance and Responsibility Mechanisms

A. Overview of Internet Governance in Turkey

Online intermediaries in Turkey are not treated differently within the framework of Internet governance in Turkey. In other words, all online intermediaries, without any classification regarding sector or services provided, are accepted as hosting providers and thus are subject to the Law numbered 5651 on Regulating Broadcasting in the Internet and Fighting Against Crimes Committed through Internet Broadcasting (hereinafter referred to as the “Internet Law”), which went into force on 4 May 2007. Per the Internet Law, hosting providers are defined as real persons or legal entities that provide or run systems that contain services and content. Therefore, all online intermediaries running systems that contain services and content are considered hosting providers, and are not responsible for checking the hosted content or whether the content constitutes an unlawful activity, pursuant to the Internet Law. This being said, they shall remove illegal content, provided that they have been informed about the illegal content.

With the increase in the volume of Internet users in Turkey, important amendments were made on the Internet Law in February 2014 in order to adapt the law to the latest changes in technology and compound the liabilities of content, hosting, and service providers. The amendments have been heavily criticized by academics, NGOs, and society and it is claimed that the amendments are aimed at suppressing and controlling the Internet, granting unlimited authority to administrative bodies, and violating individuals’ freedom of expression and right to privacy.[9] One of the amendments made to the Internet Law relates to the categorization of hosting providers. Accordingly, hosting providers, within the scope of the principles and procedures to be determined by secondary regulation, may be categorized based on the nature of their business and be differentiated in respect to their rights and liabilities. As seen in this clause, though, online intermediaries are not categorized based on the nature of their business in the present time, though they may be classified in that way in the future since the Internet Law leaves a space in this respect.

Another important document that supports the categorization of hosting providers is the Draft 2014-2018 Information Society Strategy and Action Plan of Turkey (“hereinafter referred to as Draft Action Plan”), which was formulated by the Ministry of Development and which designates the strategies and actions to be followed by 2018. One of the strategies determined in the Draft Action Plan is the “certification of e-commerce websites”. Being considered within the scope of the definition of hosting providers, e-commerce websites shall be subject to a certification process in order to provide secure shopping experiences for customers. As per the Draft Action Plan, the minimum standards for e-commerce websites must be determined by 2016 and the certificates will be given to those e-commerce websites meeting the standards. In addition to that, the e-commerce websites that do not meet the minimum standards shall be sentenced to sanctions to be determined, and a dynamic accreditation infrastructure shall be established in order to regularly audit the activities of those sites. If the actions in the Draft Action Plan are realized, this may create positive results for online intermediaries because a certification system will prove that the website is safe to use, hence users may abandon their safety-based hesitations. Also, other goals stated in the Draft Action Plan, such as the generalization of Internet access, strengthening the Internet infrastructure, and enhancing the quality of human resources can be very beneficial to online intermediaries both in their internal operation and their expansion in the Turkish market. Subject to the liability clauses of the Internet Law, the players in the telecommunications sector in Turkey are also subject to regulations prepared by the Information and Communications Technologies Authority, a technically independent organization still controlled by the Ministry of Transport and Communications.

[9] Kerem Altıparmak, Yaman Akdeniz “An Examination of the Draft Amendments on Law No. 5651” http://cyber-rights.org.tr/docs/5651_Tasari_Rapor.pdf 25.09.2014.

B. Regulations Effecting E-Commerce Ecosystem

The effect of the Turkish Regulatory environment on Internet intermediaries can be grouped into two different categories, considering their method of application. These are: (i) regulations directly applicable to the Internet intermediaries, and (ii) general rules and regulations which are applied to Internet intermediaries in certain events.

1. Regulations Directly Applicable to the Internet Intermediaries

The first group of the regulations, which are directly applicable to Internet intermediaries, consist of the above mentioned Internet Law,[10] the Law Governing E-Commerce, the Framework on the Taxation of E-Commerce, the E-Archive Regulations, the Draft Law on Data Protection, the Law on the Payment and Securities Reconciliation Systems, the Payment Services and Electronic Money Institutions (the “E-Money Law”), and the Consumer Protection Law.

[10] Since the Internet Law is one of the main topics of this study and has been discussed in other sections.

i. The Law Governing E-Commerce

The Law Governing E-Commerce numbered 6563 was reviewed and accepted by the General Assembly of Turkish Grand National Assembly on October 23rd, 2014 and published in the Official Gazette on November 5th, 2014, numbered 29166. According to the Law, its provisions are enforceable on May 1st, 2015. The Law Governing E-Commerce regulates the roles and responsibilities of e-commerce service providers, intermediary service providers, and electronic commercial communications. The E-Commerce Law explicitly states that intermediaries are not under any obligation to control the legality of the content or sales of goods provided by the users of the platform. The E-Commerce Law also stipulates that the application of the requirements regarding informing the users, sales, and electronic commercial communication will be determined by secondary regulations. The aforementioned provision has the potential to provide additional protection for intermediaries from secondary liability.

The E-Commerce Law is expected to be beneficial for intermediaries since it will regulate specifically the non-liability of intermediaries. Therefore the E-Commerce Law may solve the problems of intermediaries in cases where the courts hold them liable.

ii. Taxation of E-Commerce

Taxation of e-commerce in Turkey is based on the OECD’s “Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework Conditions” report, which was accepted by Council of Ministers in 1998. This report is significant, setting the ground principles for implementation of e-commerce taxation to international transactions. Many countries, including Turkey, are setting their national practices accordingly. Additionally, the Revenue Administration of the Ministry of Finance has published a framework regarding the responsibilities of e-entrepreneurs in relation to the application of taxation rules to e-commerce activities[11].

Most recently, the Revenue Administration published the Communiqué of the Tax Procedural Law numbered 433 on December 30th, 2013 in order to provide an e-archive invoice application to enable the electronic storing of invoices issued electronically, as well as enable B2C e-invoicing. According to the Communiqué, taxpayers that have garnered revenue of more than 5 million Turkish Liras as of 2014 must start using the e-archive invoicing application before 2016. The Communiqué of the Tax Procedural Law numbered 433 is very beneficial to online intermediaries because it allows digitalization in fiscal matters, which is a field with significant paper work.

[11] Çağatay Pekyörür, Nilay Erdem, Selen Uğur, Tugrul Sevim, Yasin Beceni, “Electronic Commerce and Taxation”, published article on “Vergi Sorunları Dergisi” (“Peer-Review Taxation Issues Journal”), Issue 293, February 2013.

iii. Data Protection

Turkey has no specific law governing the privacy of personal data. Nonetheless, there is a Draft Data Protection Law, and there are general provisions in relation to privacy and personal data protection in a number of pieces of legislations. There are some sector-based regulations in place for the telecommunications, banking, insurance, capital markets, and health sectors as well.

According to the Constitution, the right to personal data protection shall ensure that the data subject has the right to be informed about the processing of his/her personal data, others’ access to that data, requests for the data’s correction and deletion, and if the data is being used for the related purpose or not. The same article also states that personal data may only be processed under circumstances stated by law or under the explicit consent of the data subject. There are also punitive provisions set forth in the Turkish Criminal Code. Additionally, there are provisions of the Turkish Civil Code that give individuals whose personal rights are unjustly violated the right to file a civil action.

However, none of these regulations create a clear framework for the protection of personal data. The current Draft Data Protection Law is based on the EU 95/46/EC Data Protection Directive and requires explicit consent of the data subject both for processing personal data and for transferring the personal data to third parties and/or abroad, unless the processing falls under the scope of the Law’s exceptions. Absent a framework, data protection is causing problems in the data flow to Turkey, since Turkey is considered an unsecure country by EU data protection authorities. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to conduct data based activities in Turkey from abroad.

Furthermore, companies often cannot sufficiently plan their path of operation because they cannot predict when the Draft Data Protection Law will be enacted. This uncertainty generally results in personal data programs being run in accordance with the Draft Data Protection Law. However, amendments to the Draft Data Protection Law and future regulations pursuant to the law will eventually require the modification of personal data compliance programs, which means additional costs for companies, including intermediaries. Without a data protection law, personal data does not have sufficient protection, which creates doubts in the public about the usage of online intermediaries. Therefore, online intermediaries’ growth is jeopardized by the absence of a data protection law.

iv. E-Money Law

The E-Money Law was published in the Official Gazette dated June 27, 2013, numbered 28690 and became effective as of the date of its publication. The Law aims to regulate payment systems, payment services, and electronic money services, and sets forth the principles and procedures with regard to the establishment, authorization, and operation of the providers. According to the Law, payment service providers and e-money institutions should obtain license from the Banking Regulation and Supervision Authority in order to continue their activities in Turkey. One of the most challenging provisions for foreign players of such a law is the local information systems requirement. In order to obtain the necessary license, payment service providers and e-money institutions must keep their primary and secondary IT systems within the borders of Turkey.

v. Law on Consumer Protection

The new Law on Consumer Protection, which replaces the Law numbered 4077 on Consumer Protection, was enacted by the Turkish Parliament on November 7th, 2013 and will be effective six months after its publication in the Official Gazette.

According to the Consumer Protection Law, in the case of a distance contract, the consumer has the right of withdrawal within 14 days without paying any kind of penalty and without stating a reason. Additionally, the Consumer Protection Law stipulates that the intermediaries with distance contracts should keep records of transactions between sellers and buyers, and should provide such information to the relevant institutions and customers when asked. Such intermediaries are responsible to sellers and buyers in accordance with their contractual relationship. In this clause, intermediaries with distance contracts have limited liability under these contracts, and cannot be held liable for the execution of the distance contract itself because their role is limited to that of an intermediary, and therefore they are not a party to the distance contract.

3. General Rules and Regulations Applied to Internet Intermediaries in Certain Events

Furthermore, a second group of regulations exist, consisting of real-world legislations, including customs regulations, the Draft Communiqué on V.A.T., the Regulation on Importation, Production, Process and Presentation to the Market of Food Supplements, and the Regulation on Debit and Credit Cards. In certain cases, such regulations have been applied directly to intermediary platforms or to the users of such platforms for the reasons based on the type of marketed goods, the V.A.T applied to the sale, or fraudulent activity performed on the platform.

The Ministry of Finance has been drafting a new Communiqué (the “Draft Communiqué”) to merge all communiqués regarding the VAT. The Draft Communiqué includes provisions that extend the application scope of the VAT at auction places by including bargains and other types of sales that shall cause VAT. Such a Communiqué may result in additional liability for the intermediaries that have business models based on auctions.

The Regulation on Importation, Production, Process, and Presentation on the Market of Food Supplements stipulates that food operators shall register the web sites and URL addresses to local offices of the Food and Control General Directorate of the Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Livestock. Accordingly, the Regulation permits the sale of food supplements via registered URLs and stipulates fines for food operators who act against such provisions. Therefore, in order to market food supplements through intermediaries, sellers must register their URLs at intermediaries’ platforms in accordance with the Regulation.

Additionally, according to the new amendments on the Regulation on Debit and Credit Cards, offering payments with installments through credit cards is limited to nine installments (including the period of deferral of payments) in general and such service cannot be offered for the purchases of food, fuel, or for expenses related to telecommunications or jewelry. This amendment put an additional burden on intermediaries to control the sales on their platform in order to categorize goods that may fall under the payment with installments prohibition.

C. Main Governance Mechanisms

The regulators use both ex ante and ex post mechanisms in order to regulate online intermediaries. The exante instrument used by the government to regulate online intermediaries is the operating certificate issued by the Telecommunications Authority. Per the Regulation Regarding Principles and Procedures for Granting Operating Certificate to Access and Hosting Providers by Telecommunications Authority, all types of access and hosting providers shall be required to obtain operating certificates. Since online intermediaries are considered hosting providers in Turkey, before providing services they must apply to the Telecommunications Authority and obtain operating certificates.[12] Without such a certificate, the service provided by the online intermediaries shall be suspended. In other words, the operating certificate is the instrument enabling online intermediaries to provide services in accordance with the law. However, foreign online intermediaries that do not have a local entity in Turkey are excluded from the burden of obtaining the certificate because they are out of jurisdiction of Turkey.

In addition to that, the ex post mechanism described in the Internet Law also regulate online intermediaries. The provisions under the Internet Law try to balance the rights of the users and those who claim that their rights have been violated through the websites. Considering the proportionality principle, the Internet Law allows for URL blocking rather than blocking entire websites (excluding exceptional cases).[13] Accordingly, in a case where the right of a user is violated, only the web page containing the related content shall be removed; thus, the users will be able to continue their activities on the other pages of the related website.

[12] Article 4 paragraph 1 of the Regulation Regarding Principles and Procedures for Granting Operating Certificate to Access and Hosting Providers by Telecommunications Authority.

[13] As per Article 8 paragraph 1 of the Internet Law, access to an entire website on the Internet may be blocked if there is sufficient suspicion that the content constitutes crimes which are provocation for committing suicide, sexual harassment of children, easing the usage of drugs, supplying drugs which are dangerous for health, obscenity, prostitution, providing place and opportunity for gambling; and crimes mentioned in the Law on Crimes Against Atatürk dated 25.07.1951 and numbered 5816.

A. Liability Framework

Pursuant to the Internet Law, “hosting providers who do not make the hosting provider notification or do not fulfill the obligations determined by this Law shall pay an administrative fine anywhere from 10 thousand Turkish Liras to 100 thousand Turkish Liras by the Presidency.”[14] In light of this clause, online intermediaries that do not remove illegal content from broadcast once they have been informed about that content shall be fined.

Online intermediaries also become liable when they do not remove illegal content after being informed of its existence in the cases in which the content constitutes defamation, violation of trademark protection, or violation of copyright protection.

[14] Article 5, paragraph 6 of the Internet Law.

1. Defamation

As per Turkish Criminal Code, any person who acts with the intention to harm the honor, reputation, or dignity of another person is sentenced to imprisonment from three months to two years, or forced to pay a punitive fine. The content can possibly be evaluated under article 125 of the Criminal Code and the person may be charged with committing a “defamation” crime.

2. Personal Right Violations

Additionally, Turkish Civil Code designates personal rights violations. Since the right to protect one’s honor and dignity is deemed a personal right, content violating honor and dignity may be deemed a personal rights violation as well. In the event of a personal rights violation, the complainant may file a lawsuit to request the termination of the violating material, the removal of the violating thread, the examination of the content, material indemnification, moral indemnification, and/or material compensation from the violator. In regards to violations over the Internet, in practice rights holders obtain preliminary injunctions from courts for blocking access to websites on which the violating content is available. Several courts decisions have led content to be blocked from a number of different websites.

It also should be noted that the actual practice in Turkey with regards to Internet content is still vague and the application of it different judicial authorities varies. Although blocking access is a procedure that is specifically designated for a limited number of circumstances, the authors of this case study have still observed in practice that some courts may grant blocking access decisions for content for which such decisions cannot be legally made accordance with the Internet Law.

3. Crimes Against Ataturk

Moreover, Turkey has a specific law on crimes against Ataturk (Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Republic of Turkey who implemented his ideology of Kemalism positioning Turkey towards the west and continues to hold a significant place in Turkey’s history as the first president) called the Law on Crimes against Ataturk, numbered 5816 dated 25/7/1951. According to Law no 5651 on the Regulation of Broadcasts via the Internet and the Prevention of Crimes Committed through such Broadcasts, Internet sites that include content which can sufficiently be considered to constitute a crime under the Law on Crimes against Ataturk may be subject to blocking. As such, websites like Youtube can be blocked because of defamation against Ataturk. As sufficient suspicion of this crime can directly result in a blocking access decision, reports claiming defamation against Ataturk should be handled in a careful and prompt manner. Since the matter is delicate in terms of national values and sensitivities, interpretation of was constitutes “defamation against Ataturk” is wide. For example, content showing Ataturk in make-up and as a woman; remarks about Ataturk’s sexuality; remarks about Ataturk being a womanizer or drunk all carry the risk of being deemed defamatory and therefore risk prompting a blocking access decision.

The most well-known case of blocking access to a website due Crimes against Atatürk was series blockings to YouTube between March 2007 and October 2010. The first blocking was due a video in YouTube that insulted Atatürk. This ban was removed after the content was removed from the website. Between 2008 and 2010, YouTube was blocked continuously by a couple of court orders due to Crimes Against Ataturk.[15]

[15] Alper Çelikel, Blocking Access to Youtube.com from Turkey and Its Consequences from the Perspective of Freedom of Expression, 2011, https://www.academia.edu/1937347/YOUTUBE.COM_WEB_SITESINE_TURKIYEDE_ERISIMIN_ENGELLENMESI_VE_IFADE_HURRIYETI_BAKIMINDAN_SONUCLARI 26.09.2014.

4. Copyright Protection

Copyright protection is granted under the Law no. 5846 on Intellectual and Artistic Works (“FSEK”). According to FSEK, in the case of a copyright violation over the Internet, natural or legal persons whose rights have been violated shall initially contact the content provider and request that the violation cease within three days. Should the violation continue, a request should next be made to the public prosecutor, who will require that the relevant ISP suspend the service provided to the content provider in question within three days. The service provided to the content provider shall be restored if the violation ceases. Please note that Law no 5846 does not define content provider. In practice, in addition to actual content providers, blocking access decisions against hosting providers can also be handed down pursuant to this provision. MySpace and Last FM are examples of websites that have been blocked pursuant to this provision.

5. Additional Regulations

In addition to these provisions that specifically set forth a blocking procedures, Turkish courts and judges have in the past the granted blocking-access decisions based on various other regulations including:

- Turkish Civil Law,

- Law on Combat Against Terrorism,

- Actions that may constitute a crime in accordance with “Turkish Criminal Law” (especially for web sites which publish content about sensitive political issues in Turkey, such as Kurdish issue, Armenian issue etc.)

Please note that those pieces of legislation do not designate a specific blocking procedure. However, the courts did grant blocking decisions pursuant to these regulations, as well as based on temporary measures such as preliminary injunctions for personal rights violations pursuant to Turkish Civil Law. In recent decisions of the Court of Cassation, the Internet Law is a specific regulation compared to the Turkish Civil Law and is therefore applicable to personal rights violations on the Internet.[16] After that decision, courts started to apply only the Internet Law.

In addition to that, if online intermediaries do not maintain and update their indicative information accurately and completely on their own sites in a way that the users can access directly from the main page, they can pay an administrative fine of two thousand to ten thousand Turkish Liras.

[16] Court of Cassation, 4th Section of Law, Case No: 2012/2045, Decision No: 2013/1218, Decision Date: 29.01.2013. (In Turkish: Yargıtay 4. Hukuk Dairesi, E. 2012/2045, K. 22013/1218, T. 29.01.2013) http://66.221.165.113/cgi-bin/highlt/ibb/highlight.cgi?file=ibb/files/4hd-2012-2045.htm&query=5651%20Say%FDl%FD%20Yasa%20%F6zel#fm.

B. Safe Harbors

According to the Internet Law, since online intermediaries are not responsible for checking hosted content or researching whether the content constitutes an unlawful activity, online intermediaries are not liable in cases where they are not informed of the infringing content. This being said, per the Internet Law, intermediaries can be “informed” via any channel considered to be contact information under the law. In other words, the Internet Law does not designate a specific channel to contact online intermediaries about such violations.

Upon notification in accordance with the Internet Law, online intermediaries have to remove the content. Before the February 2014 amendments to the Internet Law, online intermediaries’ responsibility for removing the content was limited by technical possibilities (i.e. sufficient technologies to remove the content); however, the February 2014 amendments removed the technical possibilities limitation from the Internet Law. Online intermediaries will be punished with administrative fines in the amount of 10,000.00 TRY to 100,000.00 TRY if they do not remove content that they have been properly notified about.

As explained above, the E-Commerce Law provides a safe harbor for online intermediaries by establishing that they are not liable for third party content. However, until the E-Commerce Law is enforceable, judicial and administrative bodies cannot apply it.

C. Enforcement

Before the amendment to the Internet Law, the users who claimed that their rights have been violated through websites were first obliged to apply to the online intermediary in question in order to ask for the removal of the content. The amendment to the Internet Law has changed this “notice and take down” procedure and gives two options to users. Accordingly, users whose rights have been violated may apply to the content/hosting provider for the removal of the content, or can directly bring a lawsuit against the content provider. In other words, with the amendments to the Internet Law the “notice and take down” procedure has been evolved to a procedure of “notice/no notice block.” This amendment weakened online intermediaries’ power to apply their terms of use or other policies, and to consider disputes themselves.

Most Turkish users prefer to apply to courts rather than intermediaries. Since the courts do not have a sufficient understanding of such disputes, online intermediaries sometimes have to remove the content or block access in Turkey unfairly. Furthermore, online intermediaries have to be very quick to respond such requests because the Internet Law establishes a period of only a couple of hours for trial and enforcement proceedings.

According to the legal procedure stipulated in the Internet Law, any real person, legal entity, institution, or entity who claims that his/her personal rights have been violated may either:

- Apply to the content/hosting provider for its removal. There is no specific limitation about the method of communicating with the content/hosting provider, so the user’s application to the intermediary by filling out the reporting form would constitute a “warning to the content/hosting provider” as per the Internet law, or

- Go directly to the court and request for the URL blocking to the specific content. The court may also order blocking of the entire website if the violation cannot be stopped otherwise.

D. Significant Cases

On 21 March 2014, Twitter was banned in Turkey because of three court orders and a public prosecutor’s request regarding the removal of content. Since Twitter is one of the most popular social media websites in Turkey, the reactions against the blocking order spread on media in a very short time. Thus, in order restore access to Twitter, personal applications were made to the Constitutional Court of Turkey. On April 2nd, 2014, the Constitutional Court of Turkey stated that the TA should enforce the order immediately and ruled that such a general ban on Twitter was a violation of freedom of expression. The Constitutional Court also noted in its order that since the Internet Law provides for URL blocking, blocking access to the whole website violates the proportionality principle.[17] After this order, the Twitter ban was removed.

One week after the Twitter ban, on March 27th, 2014, YouTube was also banned due to the presence of a voice recording of a meeting of high officials, including the Foreign Affairs Minister, the Undersecretary of National Intelligence Service, and the Deputy Chief of Staff of Turkish Armed Forces. The decision stated that contents in 15 URL addresses would be removed unless access to YouTube was fully blocked. Following the blocking order, many applicants, including YouTube, applied to the Constitutional Court claiming that blocking access to the website violated their constitutional rights.

On June 13th, 2014, the Constitutional Court ruled that blocking access to YouTube constituted a violation of freedom of expression.[18] The decision of the Constitutional Court first explained freedom of expression in the scope of the constitution and human rights. In addition, the court stated that the Internet has great value for the exercise of fundamental rights and freedoms, especially for freedom of expression. Social media is now indispensable for persons to express, share, and promulgate their knowledge and opinions. Therefore, per the Constitutional Court, it is explicitly clear that the government and administrative institutions have to act responsibly while regulating the Internet and social media instruments, which have become the most effective methods of self-expression. Furthermore, the Constitutional Court ruled that there is nothing in the Internet Law that allows for blocking access to an entire website instead of conducting URL blocking or blocking with other methods that constitute a lighter-touch intervention. Therefore, the Telecommunications Authority did not have the authority to completely block access to YouTube, and the ban violated fundamental rights and freedoms of the applicants.

[17] Constitutional Court, Application No. 2014/3986, Decision Date: 02.04.2014, http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2014/04/20140403-18.pdf 26.09.2014.

[18] Constitutional Court, Application No. 2014/4705, Decision Date: 29.05.2014 http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2014/06/20140606-10.pdf 26.09.2014.

V. eBay Case Study

A. Information About eBay and Gitti Gidiyor (eBay’s Local Subsidiary in Turkey)

eBay, founded in San Jose, California in 1995, is the world’s biggest online marketplace. It facilitates users buying and selling items in almost every country worldwide, and has made advances in digital marketing, multi-channel retail, and global e-commerce. In addition, eBay reaches millions of people through StubHub (the world’s biggest online marketplace for tickets) and job posting sites that cover more than 100 cities around the world. The company is based in the US and operates as a limited liability company listed in the NASDAQ stock exchange. eBay has 97 million users and, as of 2013, was worth $212 billion.

eBay Inc. owns a series of third party e-commerce platforms worldwide, platforms where sellers exhibit their goods for sale online, as well as provide secure payment between the parties of such sales. eBay’s role is limited to providing a platform to bring together buyers and sellers; it does not engage at any point in online retail activity and does not make any legal transactions as a buyer or a seller. In 2011, eBay acquired 93% of the shares of Turkey’s leading third party e-commerce platform, Gitti Gidiyor, which operates an identical business model in Turkey. The deal followed eBay’s acquisition of a minority stake in Gitti Gidiyor in 2007.

Gitti Gidiyor was established as a company with three partners in 2001. It has more than 10 million registered users and more than 27 million visitors (with 12.5 unique visitors) per month. On average, 750,000 sales take place on the site each month, which corresponds to 1 sale every 3 seconds. The total number of sales transactions that have taken place on the site is more than 30 million.[19]

Gitti Gidiyor is a platform that provides a secure payment and communication service to its users who are carrying out e-commerce transactions. The role of a third-party marketplace platform, such as the one operated by Gitti Gidiyor, is to create a trusted online environment where buyers and sellers can trade goods and services among themselves. Gitti Gidiyor is not an online retailer, but merely hosts content created by others. The users of Gitti Gidiyor, in addition to creating the content themselves, carry out transactions on the online platform without any involvement of the company itself. Users do not involve the company at any stage of the sales and, further, Gitti Gidiyor is not a party to the sales agreement. One of the main features of Gitti Gidiyor is its “Zero Risk” payment system. The “Zero Risk” payment system aims to provide a safe method of payment for online transactions, where the rights of both the sellers and purchasers are protected during the process of delivery and examination of the product.

[19] These numbers are abstracted from the information on Gitti Gidiyor’s website at http://www.gittigidiyor.com/hakkimizda/tarihce.

B. Challenges for eBay as an Intermediary Operating in Turkey

In certain cases, Gitti Gidiyor is deemed liable – just like the actual perpetrator of a crime or an infringer – for the unlawful acts conducted on the platform and/or in relation to the products sold on its platform. Some examples of such liability problems are as follows.

1. Challenges Related to Customs Issues

Since it is not possible for Gitti Gidiyor as a hosting provider to see, know, or evaluate the exact nature or origin of the goods traded by its users, Gitti Gidiyor has no legal or criminal liability in relation to the goods that are sold or offered for sale on its platform. Gitti Gidiyor is recognized as a “hosting provider” under the Internet Law by the Information and Communication Technologies Authority’s (ICTA) Telecommunications Directorate. As explained above, according to the Internet Law hosting providers like Gitti Gidiyor have no responsibility to check the content that they are hosting or to proactively investigate whether their users breaking the law.

Despite the fact that Gitti Gidiyor as an intermediary has no control over or knowledge of the transactions carried out by buyers and sellers through its platform, certain Customs Enforcement Directorates have held Gitti Gidiyor liable for breaches of Anti-Smuggling Law No. 5607 (“Law No. 5607”) through an interpretation based on the assumption that Gitti Gidiyor acts as a mediator in the sale of smuggled products by users on its platform.

Law no 5607 Article 3 includes an exhaustive list of acts deemed to be “Smuggling Acts”, which does not include “acting as a mediator in the sales of smuggled goods.” In addition to the fact that the law does not include such an act on its exhaustive list, it is not Gitti Gidiyor but the buyers and the sellers who carry out the transactions on the platform by reaching an agreement about the sale price, characteristics, and delivery conditions of the product. It is without a doubt that Gitti Gidiyor is not a party to such sales contracts between the related buyers and sellers. Therefore, Gitti Gidiyor cannot be held liable under Law No. 5607.

In a case regarding Law No. 5607, a customs enforcement directorate made a complaint to the public prosecutor and requested that he press charges against Gitti Gidiyor, claiming that Gitti Gidiyor was helping its users to commit smuggling crimes. After the investigation, the public prosecutor filed a case to a criminal court. These claims were rejected by the court[20] for the reason of the non-liability of Gitti Gidiyor as an intermediary. However, the court did not specifically reference the Internet Law, which regulates non-liability of the hosting providers. Instead, the court stated that it was impossible for Gitti Gidiyor to control all the products sold through its platform, and it therefore cannot be held liable from a criminal law perspective, since it did not commit a negligent act.

[20] Criminal Court of First Instance, Hatay, Case No: 2011/1030, Decision No: 2012/595, Decision Date: 18.04.2012, approved by the decision of the Court of Cassation, 7th Section of Criminal Department, Case No: 2013/21432, Decision No: 2014/12444, Decision Date: 18.06.2014.

2. Challenges Related to V.A.T. Liabilities

The Ministry of Finance is drafting a new Communiqué (the “Draft Communiqué”) to merge all communiqués regarding the VAT. The Draft Communiqué includes provisions that extend the scope of the VAT at auction places by including bargains and other types of sales that shall cause VAT. It is not clear whether e-commerce intermediaries that provide financial and commercial activities to others will be deemed auction-style platforms, or whether such intermediaries will be deemed auction-holders.

3. Challenges Related to Sales of Products

The sale of products of a specific nature is another issue for platforms like Gitti Gidiyor. Such products of a specific nature are pharmaceutical products, tobacco and alcohol, food supplements, guns and firearms, historical artifacts, etc. E-Commerce platforms tend to ban the sale of such products and they also use technical tools to avoid such sales. However, because many people use such platforms and many transactions are realized on them, it is easy to miss single sales or offerings. Turkish authorities have the tendency to initiate actions against e-commerce platforms in relation to such sales or offerings without first notifying the platform about the issue and asking for removal.

C. Impact Assessment of the Challenges

The problems of eBay-Gitti Gidiyor in Turkey have mainly resulted from the lack of understanding in Turkey about the principle of “non-liability of intermediaries” provided that they meet certain obligations. One of the other reasons for the problems is the fact that it is more difficult to find the actual perpetrators of a crime if such a crime is committed online. As finding such actual perpetrators is difficult, the administrative and judicial authorities tend to hold Gitti Gidiyor liable for issues related to its platform. Be it customs, V.A.T., advertising, distance sales, the main idea behind this problem is the fact that authorities in Turkey tend to deem hosting providers (or intermediaries in the international terminology) liable and/or try to sanction them for actions and/or content on the platform that they are providing.

In addition to being contrary to the principle that a platform like Gitti Gidiyor cannot be held criminally or otherwise liable for the activities of the users, as laid down in European Union harmonized legislation, as well as the corresponding legislation in Turkey, the misinterpretation of the Law No. 5607 could have far-reaching negative consequences for the development of e-commerce in Turkey, and for much-needed local and foreign investment in this field. Problems with the V.A.T. liabilities and sales of products are another example of how an e-commerce business model may be treated the same as the actual provider of a service and expected to meet the same requirements as such parties.

The above problems caused by a lack of understanding of the non-liability principle hamper the growth of the online intermediaries in Turkey and damage the willingness of the foreign online intermediaries to enter into the Turkish market. Furthermore, these problems concern users, as it appears online intermediaries may be conducting illegal activities and therefore may be dangerous to use. As can be seen, this lack of understanding has many negative effects on online intermediaries.

D. Recommendations/Solutions in Light of the Specific eBay Case

As mentioned, the above problems result from the fact that an intermediary non-liability regime is not clearly imposed in the judicial and administrative environment of Turkey. In light of this finding, our recommendations are:

- Turkey should closely follow the developments of policy, strategy, and action plans, as well as the legislation, of countries where e-commerce is developed and Turkish authorities should clearly understand the ratio legis (the reason of enacting the law) behind such documents, in particular regarding the non-liability of e-commerce platforms.

- The regulations and policies to be implemented by the Ministry of Customs and Trade’s Internal Trade General Directorate (the organ given authority by the E-Commerce Law) in relation to newly enacted E-Commerce Law, which clearly imposes the non-liability for e-commerce platforms, will be of high importance. A structure should be established where public authorities think and act in cooperation with private sector representatives and civil society when making or amending policies and legislation.

Legislation on e-commerce may solve most of the problems intermediaries are facing, especially in the field of liability. The previously mentioned structure is a key element to monitoring international development, and therefore it may significantly effect e-commerce legislation. It appears that the above mentioned elements are connected and must be applied in combination to achieve success.

VI. Conclusion

Our studies of online intermediaries in Turkey show that Internet usage is spreading in the country and the society is at the beginning of exploring the potential of the Internet in the economy, politics, socializing, and charitable action. Within this exploration process, national intermediaries – both imitations of international online intermediaries such as Facebook and Twitter, and unique ones – are beginning to flourish in the country. Also, society is beginning to use online intermediaries in different ways and is eager to expand both the usage of the Internet and these platforms. It should also be stated that despite the government’s unsupportive statements towards social media, social media usage is continuing to rise due people’s need to communicate and express their opinions. Consequently, it is widely expected that Internet usage will continue to spread across the country, and therefore online intermediaries will gain more and more popularity in the future. This will cause inevitable changes in the economy, politics, and social life in the near future.

Although people are generally willing and eager to use the Internet and online intermediaries, the legislative and administrative environments are somewhat hostile towards both the Internet and online intermediaries. Government efforts to control and suppress the Internet and online intermediaries have not been successful so far due people’s willingness, technical impossibilities, and court decisions. However, these efforts have caused loss in prestige for the government internally and externally. Furthermore, the absence of data protection laws and e-commerce laws is an obstacle facing the development of online intermediaries in Turkey. The government’s unwillingness to enact the above mentioned laws – combined with its efforts to control and suppress of Internet – has been heavily criticized. Taxation problems and credit card installment limitations are other problems that online intermediaries are facing that are directly affecting them economically. Although these may be justified by referencing the public interest, such as reducing the current deficit and increasing tax income, these problems are damaging the growth of online intermediaries in Turkey.

An important aspect of the Internet Law is its requirement for online intermediaries to obtain operating certificates. Operating certificates allows the government to know who owns and controls the online intermediary and apply the law (when necessary) directly to this owner, as well as conduct communications regarding the government’s requests through the provided contact information. However, while operating certificates may seem a tool of control for the government, they have a benefit for online intermediaries in that they prove the owner is a hosting provider and therefore not responsible for the content it hosts. Another control mechanism of the government is the ability to block access to websites. Although this is not a precise solution since a block can easily be circumvented, it allows the government to force intermediaries – especially foreign intermediaries – to obey Turkish law and court orders.

The liability of online intermediaries is mainly regulated under the Internet Law and a couple of other laws that include relevant provisions. Although the Internet Law accepts that online intermediaries are not responsible for the content that is created by their users, there are problems with this aspect of the law, in that the courts do not always accept it. Furthermore, the access blocking mechanism causes damage to online intermediary even though they are not responsible for the content. Therefore it can be said that the online intermediary is forced to control the content created by its users even though it cannot be punished pursuant to the law. Moreover, there is no obligation for the applicant to notify the online intermediary before removing content. The website of the online intermediary can be blocked even without knowledge of the online intermediary.

In the eBay-Gitti Gidiyor case, the effects of the unawareness of the principle of non-liability of online intermediaries can be easily seen. Challenges faced by Gitti Gidiyor in customs, product sales, and taxation clearly show that administrative and judicial authorities in Turkey are not applying the principle correctly. Considering Turkey is a developing country with a young population, which means Turkey is a huge market for online intermediaries, misconduct of administrative and judicial authorities affects society in many ways. This study recommends that the application and quality of the current legislation should be improved by cooperation of public institutions, the private sector, and NGOs.

Bibliography

Legislation

Anti-Smuggling Law No. 5607 (Published in the Official Gazette dated March 31st, 2007 and numbered 26479)

Communiqué of the Tax Procedural Law numbered 433(Published in the Official Gazette dated December 30th, 2013 and numbered 28867)

Constitution of the Republic of Turkey (Published in the Official Gazette dated November 9th, 1982 and numbered 17863)

Consumer Protection Law (Published in the Official Gazette dated November 28th, 2013 and numbered 28835)

Draft Communiqué on V.A.T. (Pending at Revenue Administration to be enacted)

Draft Data Protection Law (Pending to be presented to the Parliament)

Law no. 6563 Governing E-Commerce (Published in the Official Gazette dated November 5th, 2014 and numbered 29166)

Law no. 5846 on Intellectual and Artistic Works (Published in the Official Gazette dated December 13th, 1951 and numbered 7981)

Law numbered 5651 on Regulating Broadcasting in the Internet and Fighting Against Crimes Committed through Internet Broadcasting (Published in the Official Gazette dated May 23rd, 2007 and numbered 26530)

Law on Crimes Against Atatürk (Published in the Official Gazette dated July 25th, 1951 and numbered 5816)

Law on the Payment and Securities Reconciliation Systems, the Payment Services and Electronic Money Institutions (Published in the Official Gazette dated June 27th, 2013 and numbered 28690)

Regulation on Debit and Credit Cards (Published in the Official Gazette dated December 17th, 2010 and numbered 27788)

Regulation Regarding Principles and Procedures for Granting Operating Certificate to Access and Hosting Providers by Telecommunications Authority (Published in the Official Gazette October 24th, 2007 and numbered 26680)

Turkish Civil Code (Published in the Official Gazette dated December 8th, 2001 and numbered 24607)

Turkish Criminal Code (Published in the Official Gazette dated October 12th, 2004 and numbered 25611)

Court Decisions

Court of Cassation, 4th Section of Law, Case No: 2012/2045, Decision No: 2013/1218, Decision Date: 29.01.2013.

Criminal Court of First Instance, Hatay, Case No: 2011/1030, Decision No: 2012/595, Decision Date: 18.04.2012 (approved by the decision of the Court of Cassation, 7th Section of Criminal Department, Case No: 2013/21432, Decision No: 2014/12444, Decision Date: 18.06.2014).

Constitutional Court, Application No. 2014/3986, Decision Date: 02.04.2014, http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2014/04/20140403-18.pdf

Constitutional Court, Application No. 2014/4705, Decision Date: 29.05.2014 http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2014/06/20140606-10.pdf.

Articles and Reports

AFRA, Sina. “Common Ground of Digital Markets E-Commerce: Place of Turkey in the World, Current Situation and Steps for the Future,” Turkish Industry and Business Association, July 2014.

Pekyorur, Erdem, Ugur, Sevim, Beceni. “Electronic Commerce and Taxation,” Vergi Sorunları Dergisi” (“Peer-Review Taxation Issues Journal”), Issue 293, February 2013.

“Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework Conditions,” OCED, Report by the Committee on Fiscal Affairs, as presented to Ministers at the OECD Ministerial Conference, “A Borderless World: Realizing the Potential of Electronic Commerce” on 8 October 1998.

Prof. Dr. B. Bahadır Erdem, “Turkish Citizenship Law,” 3rd Edition, Beta Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 2013

Online Resources

GittiGidiyor. “About Us.” http://www.gittigidiyor.com/hakkimizda/tarihce.

Global Web Index. “Wave 11.” https://www.globalwebindex.net/.

The World Bank. “Internet Users (per 100 people).” http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2.

TurkStat. “Use of Information and Communication Technology in Enterprises.” http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1048.

Alternative Informatics Association. “An Examination of Gezi Park.” https://www.alternatifbilisim.org/wiki/Gezi_Park%C4%B1_De%C4%9Ferlendirmesi.

Kerem Altıparmak, Yaman Akdeniz. “An Examination of the Draft Amendments on Law No. 5651.” http://cyber-rights.org.tr/docs/5651_Tasari_Rapor.pdf.

Alper Çelikel. “Blocking Access to YouTube.com from Turkey and Its Consequences from the Perspective of Freedom of Expression.” 2011. https://www.academia.edu/1937347/YOUTUBE.COM_WEB_SITESINE_TURKIYEDE_ERISIMIN_ENGELLENMESI_VE_IFADE_HURRIYETI_BAKIMINDAN_SONUCLARI